Song Dynasty (960- 1279) Military Overview Part 1- A Realm Reborn: 宋代军事概要 1 - 浴火重生

Music: Resurrection of the Dragon

Figure: JiaoZong Model Song Dynasty Taizu Emperor

Zhao KuangYin 1/6 Action Figure. Helmet inspired by stone sculpture

from the warlord Wang Chuzhi's tomb. China, Five Dynasties period, 922 AD

The Song dynasty (960- 1279) was characterized by two contrasts, great internal flourishing~ consisted of economic, scientific, and cultural developments, contrasted with sustained high external pressures exerted by many of its ambitious rivals on its peripheries. This meant that for the Song state, it was constantly under threat and hammered on its borders.

Heavy armor of a Song dynasty general: Helmet with split double plume outlined in Wujing Zongyao (lit. "Complete Essentials for the Military Classics") written during the Northern Song dynasty in 1044.

Despite its largely defensive posture compared to more militarily assertive dynasties like the Han, Tang, and Qing, Song nonetheless represented a distinct period in world history where peerless strides were made in the field of military technology- including fielding of the first firearms, rocketry, bombs and (East Asian) flamethrowers. What's more, considering the capabilities of the enemies the Song faced (including the Mongol Empire at its height) and its ability to withstand such pressure for centuries: the Song proved itself more enduring than legions of other peers across Eurasia. It was also in this pressurized crucible that Chinese armies fielded some of the heaviest armors in battle.

Figure 1. Song dynasty bronze visor unearthed in Liaocheng, Shandong. Figure 2. Contemporary face guards (1115~1234)- likely Jin. Visors 面甲 (lit) "Face Armor" have been mentioned in Chinese records and treatises, however details regarding their constructions and specifics are sparce. They were recorded more prominently during medieval Chinese dynasties: especially those of the warring northern states of Song, Liao, and Jin dynasties and later Mongol led- Yuan dynasty. With most archeological examples unearthed from the Jin regions.

Late Tang- 5 Dynasties and 10 Kingdoms era warrior. Stone sculpture

from the warlord Wang Chuzhi's tomb.

INHERITORS OF THE BROKEN DRAGON

Northern Song dynasty at a glance: Northern Song (Red) and its 2 main regional rivals: the Khitan- led Liao Dynasty (Gold) to its northeast, and the Tangut- led kingdom of Xixia (lit. "Western Xia": in Gray) in the northwest. All 3 were major players by the end of 7 decades of post- Tang civil war and anarchy known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. During these times, the already strong Khitans in the northeast gained momentum and made ambitious forays into central China. It was also at these times Xixia made their ambitious bid in the west.

The Song dynasty's organization was highly centralized with much of the power reserved in the imperial court- (thus its civilian government helmed by scholar- officials.) This footing came at a cost to the initiative of its military commanders, who were often subjected to rigorous imperial oversight. However this posture is logical considering the prior 7 decades of high warlordism and civil war. During the Northern Song, half of the empire's army of 1 million soldiers was stationed in and around the imperial capital of Kaifeng, with the best being elite palace guards and metropolitan armies which formed the core of the imperial forces.

禁軍 jinjun lit: The Forbidden Army. The Song military ensured that the court can outmatch any other regions of the realm. The Song Forbidden Army had three units. Initially there were two the Palace Guard Command 殿前侍卫司, then the the Metropolitan Command 侍卫亲军马步司. Soon however the Metropolitan Command was subdivided into the Metropolitan Cavalry Command and the Metropolitan Infantry Command. Together they were commanded under three marshals (sanshuai 三帅). To retain the primacy of the court, only the Emperor can simultaneously command the 3 units.

A heavy cataphract in Song armor- from the Northern Song painting《免胄图》by Li Gonglin (李公麟, 1049–1106) showing the Tang dynasty general Guo Ziyi accepting the surrender of the Uyghur Princes. Although the subject is Tang the armors were depicted in anachronistic Song fashion. Though the Song did possesses heavily armored cataphracts, it was not in possession of key horse raising pasture regions in the north.

Art by Shuai Zhang. Process of a Song dynasty soldier donning his armor. Traditionally Chinese armor had long had its weight rested on the shoulders and held down by straps. A (visually distinctive) solution to mitigate the heavy burden is to use the belt (and its wraps) to fasten the armor around the wearer's waist. Thereby more evenly distributing some of the burden.

Music: The Five Tiger Generals

A REALM REBORN: CONSOLIDATION

The fall of the Tang and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdom period (all 7 decades of it) is quite a galaxy in its own and one day will have its own coverage of it. But that is not the purview of this article.

Painted statue of Manjushri Bodhisattva with pagoda in hand. Dazu Stone Statues, near the city of modern Chongqing. Most were sculpted and erected during the Song dynasty. During the Song this area of the Chengdu plain was considered one of the wealthiest regions in China.

To summarize the rise of the Song dynast in as few sentences as possible: its founder Zhao Kuangyin was a very capable commander who had the misfortune of being born in the north during this era. The reason the period was called the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period was because the north was largely geographically intact under a single ruling house while the south was mostly a patchwork of 10+ simultaneous competing kingdoms. However the northern dynasties rapidly deposed one another creating a carousel of unstable "dynasties."

Being a capable military commander meant Zhao was a prized asset. His family came from humble origins but his father prove himself as a minor commander in one of the northern dynasties (Later Tang.) Zhao similarly found service in the following Later Han dynasty which briefly ruled northern China. However Latern Han was swiftly deposed by one of its generals, who established a new state that ruled over the north called Later Zhou. The ruler of Later Zhou saw great potential in Zhao Kuangyin and made him the head of the commander of the imperial palace guard.

Blunt Instrument: after his elevation into the imperial guard Zhao Kuangyin once distinguished himself in battle against a much larger host of (then winning) Liao army that was sweeping through the battlefield but through his charisma and suicidal braveness his section managed to miraculously turn the battle, thereby attaining even higher appointments.

Though of the typical stock of strongman warlords, as emperor he nonetheless could show great gentleness for the sake of future peace for the realm- notably in that he successfully persuaded his powerful generals to retire and then rewarded them after disarmament with generosity. His even handedness in application of both decisive military prowess as well as gentle terms for those who surrendered (including rival kingdom's rulers) allowed him to consolidate Song hold over all of the south, then turned to the north.

Credit: 浪人刘小黑

However, when Zhao's patron emperor died, leaving behind only a 6 year old as his heir, Zhao and his brother mutinied and then took the capital for their own. The Song dynasty was born and over the next 19 years it would then go on to subdue and reunite the rest of the disparate feuding states inside the Chinese heartlands.

INNER PEACE: FOREIGN PAINS

Previous unsuccessful Northern dynasty stratagems often focused on crushing their northern rivals then sweep south after the whole of north had been pacified. The results were disappointing, the northern dynasties fought against the small but highly militarized state of Northern Han (sponsored by Khitan Liao) many times and was unable to overrun it. However Zhao Kuangyin shifted this plan. Instead, the Song veered south and began to forcibly integrate or annex the various much weaker southern kingdoms. The plan worked well and after 2 decades of war all were either defeated or surrendered. Unfortunately, despite internal pacification and disarmament, externally, the Song was still threatened. Wolves were at its northern gates, and wolves would remain until its fall.

Elephant Art by: Topi Pajunen. This was the last time elephants were used in Chinese warfare, and soon to be followed by the first time where massed gunpowder weapons were used. Through cunning, gracious diplomacy, and at times, brutal onslaught, the Song reunited China on this heap of victory.

It was a prolonged slog, and those kingdoms that did fight the Song did put up a significant fight. When the Song dynasty invaded Southern Han in 970- which kept a permanent corps of war elephants, the massed Song crossbowmen routed the Southern Han elephants. This was the last time elephants were used in Chinese warfare. In 975, against a major southern rival, its navy was destroyed by the Song through the use of such fire arrows and bombs.

Though in hindsight the retirement of many Song generals might be seen as problematic- especially after Zhao Kuangyin's untimely death before finishing the reunification of China and the mantle of Emperorship passed to his much less militarily capable brother: it should be remembered that nearly all of the Five Dynasties' history was a frenzied cycle of mutinies by powerful generals and disloyal warlords and bodyguard units acting like Praetorian guards in assassinating their leaders. Because Jeidushi positions were hereditary and tied regions with its ruling military families. Like feudal warlords often if their interests were not met they switched sides, couped or butchered their foresworn rulers. Song was right in singling them out as grievous agents of instability and division.

A political nightmare. During the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period the small kingdom of Northern Han (Brown), located at the gate of the Great Wall emerged during the high chaos in the north occupied a highly unenvious position. It was wedged right between the great military state of Later Zhou (which later became the Song dynasty,) and the powerful Khitan empire of Liao. Furthermore, they also bordered the aggressive Tanguts who would later found the state of Western Xia in the west. Like Sicily during the preludes of the Punic War between Carthage and Roman Republic. The competition to possess this territory eventually led to all out hostility between the Song and Liao. And also later between the Song and the Jin dynasties for the next 200 years. Ultimately Song attempts to recover the north promulgated the catastrophic war with the Mongols that led to the total destruction of the Song.

Music: The Monastery

FLASHPOINT: THE SIXTEEN PREFECTURES

Despite internal pacification and prosperity, the Song found itself in heated contention with its powerful neighbor to the north. The Sixteen Prefectures of Yanyun- once part of the few early northern dynasties and was then signed away to the Khitans for their military support- was a highly volatile and geopolitically significant border between both the Liao and Song, and both empires soon warred for the possession of it. Despite early Song victories against the Liao after Song and the Song annexation of Northern Han, the Liao quickly regained the upper hand.

The Sixteen Prefectures of Yanyun consisted of north of Shanxi and Hebei province. Dotted with difficult mountains and entrenched mountain passes- whoever possessed it has major advantage in terms of initiative to launch war on the other. Whoever possessed it has an extensive stretch of natural and manmade barriers and whoever did not only has flat lands ripe for invasion. The Song was rare in that it waas one of the few united Chinese imperial dynasties that does not have the stretch of the Great Wall secured. Hence its insecure posture and paranoid overcompensation.

For the vast majority of the Northern Song dynasty- the Khitan- led Liao empire would be Song's main arch rival. The Khitans were excellent cavalrymen and their state was well organized. One should not forget that after the implosion of the Tang large numbers of Tang subjects in the north submitted to the Khitans and the wise Khitans happily made use of the former Tang subject's service.

The Khitan imperial domain could be bigger, in fact in the previous century it had proven to be able to do so. The Khitans themselves (above) knew well of this. The Sixteen Prefectures were initially ceded to the Liao for their military support to Later Jin (a struggling Northern dynasty) who assumed a humiliating subordinate position to the Liao. However when they later tried to back out from the submission the Liao under the strong Emperor Taizong of Liao:- Yelü Deguang invaded and crushed Later Jin, becoming the ruler of the northern Chinese heartlands with the ambition to become the Emperor of all of China. However their hold was brief, when rebellions sprouted across the Central Plains they returned home north.

During the Tang the Khitans and Tang had continuous clashes for centuries along their mutual border. However the Khitans eventually gained an upper hand in the 9th and 10th centuries. With a largely meritocratic leadership of war- minded princes and emperors the Liao consolidated nearly all northeast of the Song under their sway.

A Song Minister in his distinctive vermilion silk court robes, and most of all, their black Zhanjiao Putou 展角幞头 (lit. "Horned Head Cover") official's hat.

During multiple Northern Song Emperor's rule the Song launched (over) ambitious expeditions to wrangle the Sixteen Prefectures with mostly mixed results. Having monopolized the prized pasturelands for war horses Liao often bested the Song armies in their constant clashes. In most of these wars the best outcome for the Song simply meant breaking even, then return to a precarious status quo in danger of being invaded again.

NORTHERN SONG RESPONSES

Northern Song Cataphracts on imperial parade: the front row were equipped with huge crossbows (nu) the 2nd row bows and arrows, and 3rd row lances. The extremely long prods of the crossbows and the inclusion of the distinctive D shaped stirrup (the hoop on the top of the crossbow) have led many to surmise these weapons were drawn while dismounted then reserved for a deadly long range volley at a critical moment. Important to note the Song (and much medieval Chinese armies from Tang- Ming) often if not always paired crossbowmen units with archer units (Song had 2:1 ratio) as the bow compensated for the crossbow's slow reload and the crossbow compensated for the bow's lack of armor penetration. Modern stylized rendition here.

Khitan Liao cataphracts: The painting is a rendition of a Han dynasty lament poem, but the Xiongnus portrayed anachronistically as Khitans (distinguished by their bald pate and 2 sideburn ponytails.)

Compared to the height of the Tang dynasty which were able to field as much as 700,000 warhorses for its war efforts, the Song could only manage to raise some 200,000 at its own height during the Northern Song. Despite these handicaps, as we shall see, the Song compensated and found new solutions that stabilized their own playing fields.

Example of Chinese barding. The early 3 century of the Song dynasty from the 900s- late 1200s would see some of the heaviest cavalry deployed by nearly all warring states. Notably the Song for nearly all of its history would have the least access to prized war horses and vital pastures to raise war horses.

Music: Battle of Phoenix Hill

THE RENAISSANCE OF CROSSBOW

The First Golden Age of Chinese Crossbow: Han dynasty mass deployment of the crossbow. During the Han 1 millennium ago the crossbow was the main weapon of the Chinese armies. During the Song it would see it's second golden age.

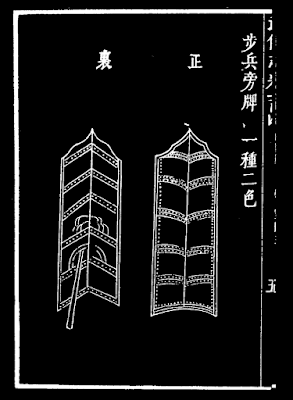

Well Armored Infantry Blocks: The Song did have a robust military industrial complex. Armories, bolt makers, and later on gunpowder manufacturers were deeply integrated with the imperial military. Not only were Song crossbowmen well protected by pavises and augmented with nearby archer units that complemented their weaknesses, Song crossbowmen were also well armored. Some of the heaviest armored wore a variant of the 步人甲 Bu Renjia armor (right though they were made lighter) they weighed around 30 Kgs- and those worn by archers and especially crossbowmen were made slightly lighter by 5 Kgs. However a problem of this is the hefty drain on the imperial treasury.

He wears a wide brimmed felt hat called Fànyáng lì 范阳笠- distinguished by its domed top and plume. It is secured around the jaw with a strap. The Fanyang li were frequently wore by soldiers on campaigns from foot soldiers to meritorious officers- example of a Song garrison veteran. Song infantry typically wore a scarf over neck and rough overcoat. Calabash gourds serve as canteens. For melee combat he is armed with a one sided slashing chopper. The heaviest crossbowmen would be armored with heavy lamellar helmets.

Example on a general:

Immovable As The Mountain: Heavy Song dynasty crossbowmen. Song discovered massed armor piercing crossbowmen were the best remedy for waves of heavy cavalry. Song crossbowmen were drilled to hold their position as if they were line infantry. The crossbowmen were protected by nearby archers and by the Southern Song dynasty they were also protected by very heavily armored infantry wielding halberds and horse choppers.

"Nu" or the Crossbow- was invented in the late Spring and Autumn period and deployed in vast numbers during the Warring States period. Once, the crossbow were equipped in staggering numbers the Qin army had some 50 thousand of such troops and the Han (early Han still retained universal conscription service) made further mass adoption of such weapons. In one of the Han Dynasty armament records (《武库永始四年兵车器集簿》) there were 520000 crossbows in the arsenal, but only 70000 bows. Bolts were numbered over 11 million.

Han dynasty bronze 3 piece triggers. Excavated Tang dynasty crossbow pieces only a few centuries prior to Song still retained this time- tested design. It's conservative to conclude that the Song did not deviate much from this trigger. Existing artworks and manuals also supports this.

In both contexts the weapon was extremely optimal in democratizing killing power: Unlike bowmenship, which takes a life time to perfect, the crossbow as well as its trigger mechanisms are very easy to use by even the simplest of the enlisted.

Chinese Pavise with foldable leg and Song dynasty "Divine Arm" 神臂弩 crossbow with stirrups and horn bow prods. By the Song dynasty the technology has advanced to such a degree that crossbows made of mulberry and brass crossbow in 1068 that could pierce a tree at 140 paces. The Divine Arm itself was reputedly able to shoot as far as 240 paces and effective at killing around 150 paces. A "D" shaped stirrup hoop were added to the top of these bows and when fired from behind a wall of pavise in concentrated volleys (yes, volleys: we will discuss in detail next) they proved devastating to even well armored crashing waves of armored enemy horsemen.

Elite crossbowmen were also valued as long-range snipers; such was the case when the Liao general Xiao Talin was picked off by a large Song crossbow at the Battle of Shanzhou in 1004. His death in the heat of the fray caused the Liao army to retreat. Song fielded twice more crossbowmen than archers but often paired deployed crossbowmen with archers nearby to cover each's weaknesses.

One should remember things and subjects are not isolated- especially in history. That this clever deployment of Song crossbowmen blocks were not deployed in isolation but in CONJUCTION with normal Song efforts and campaigns. At times especially aggressive Song generals like Yang Ye (who was a hero of Northern Han) and his son were able to defeat a formidable Liao army of 100,000 at Yanmen pass in 980 and repeated his great success 2 years later once again against the Liao, attacking well deep into Liao controlled parts of Shanxi. However the Song culmination to throttle Liao in the north in 986 was resoundingly defeated by the Liao army commanded by the regent Empress Dowager Chengtian who broke the Song army and slew Yang Ye.

The Song crossbowmen were instructed to behave thusly. In previous centuries the crossbowmen- despite their efficiency were terrified of coming cavalry charges. The Song specially trained its own crossbowmen to mitigate that fear by standing firmly and as a unit train their deadly barrage right on the center of the enemy's armored mass (remember heavy cavalry charges are always tightly clustered before impact.)

Another even more powerful version of the crossbow were later fielded called the 克敌弓 Kedi nu lit. "enemy vanquishing crossbow"

When left to their own devises. Active shooters will station beside the screen of pavises and shoot at incoming enemies while those who needs to reload will drift to the center. In this way the two will work interchangeably (so that those facing out will always be able to deliver fresh volleys) while those at the center finishes their reload and return to their shooting positions. With these reforms, the Song were able to achieve a state of parity against its many challengers. The crossbow would be heavily fielded throughout the dynasty.

After the aforementioned Song/ Liao wars, the initial Song ambition to recover much of what was the Tang north (now Liao holds) dampened. Instead the Song opted for internal self strengthening. The Grand Councilor Song Qi surmised that Song military's weakness stemmed from the fact that it perennially lacked enough horses while nearly all of the good war horses were monopolized by the northern peers.

Instead, Qi proposed a lasting peace and to demarcate a well defined border with its northern neighbors along the course of the Baiyangdian (lit. "White Sea Lake") lake and its river. The Liao agreed with the proposal, this gave the Song court the chance to care for internal matters: 守内虚外 shounei xuwai (lit. "keep the inner and ignore the outer."

PART 2: CONTINUED HERE

%20(1)-%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

%20(1)-.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

This is what I find interesting about Japan's analysis and adoption of aspects of Chinese, specifically T'ang civilization. What's interesting is not what they adopted for their own, namely architecture, Buddhism, writing, courtly culture and literature ... it's what they analyzed about China and actively rejected, namely Meritocracy, the Examination System, civilian rule over the military, the Mandate of Heaven, everything that makes China Chinese, the Japanese rejected. They adopted those aspects of T'ang China that reinforced their Aristocratic and hierarchical system instead.

But back to the topic: yes I find this interesting as well. I usually regard states that are able to integrate new meritorious self- made blood into its ruling ranks with more favor because it speaks to a level of competence in the ranks. This is why I look up to states that were able to be meritocratic enough to rapidly promote competent figures than states that are too static in terms of hereditary aristocracy. Generally I find periods where Japan's court broke down and essentually nobodies like Kusunoki Masashige, Oda Nobunaga (and Hideyoshi) and Ōkubo Toshimichi and men like him far more interesting. If a hereditary clan is too static, as we see in many rajputs and Austrian Ducal houses then I worry for their long term position. This by extension is applied ofc to Chinese imperial dynasties.

And although while each dynasty's fall is tragic to them and their ardent supporters. At times it's also needed because of stagnation and ill- rule. So as much as the fact it could be disruptive if it could mean that there would be restoration of more competent rule its not reductive. This will sound controversial but this is one of the main reasons in regards to dynasties such as the Ming when paired with say~ the likes of Kangxi and a century of able Manchu rule I don't find it a catastrophe.

And in regards to Song dynasty as a whole. Yes, I do find the period remarkable. Younger me often obsesses over military men and their feats but as a state Song was a economic and scientific powerhouse. Yes, its upward mobility for civilian officials, and later great upward mobility for military officials are also to be commended as well. What a -> state <- it was despite all of its flaws. Never mind the fact that so many of Eurasian state were crushed by the Mongols right after first contact or after 1 battle but the Song~ a nation of tinkering bookworms as some might have derided, held on far far longer than the rest.

For general topic, try Needham, Joseph (2008), Science & Civilisation in China, or David Graff, the latter is both more generalized and at times delves too deep in a niche. However key thing is that David Graff's first book does not cover Song. If you are interested in other CCs or enthusiasts covering this era try Historium, if you find a forum that is constructive and not Sabaton level ask them about good refs.

There is also some other authors that I have been recommended to but not got to like Peter Lorge so I can't attest to their content. Another's Beck, Sanderson's bulletin on, "Liao, Xi Xia, and Jin Dynasties 907–1234" This one should be the most topical if this era is the one you are interested in: Rossabi, Morris (20 May 1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries

If you are familiar reading with google auto translate I recommend cross reading both the sources in Chinese and also western sources. Better yet skip to Japanese and Korean sources on the topic. Especially Korean ones regarding Jurchens and Liao. Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea

Hope this helps!