In outrage they came, full of long- nurtured fury. On May 28th, 1059 BC, an assembly of the most dangerous men of the west gathered in conspiracy. That very night, Heaven spoke.

The year was 1059 BC, one century after the Homeric Trojan War, and one century before the Biblical King David's reign. In this part of China two hostile worlds were poised on a sword's edge, the culmination of almost a decade of blood-stained Cold War. On one side, it was the twilight of the great Shang dynasty- which had imposed resplendently for half a millennium across China's heartland, though its king did not know that both he and his ancient kingdom would soon be furiously swept away. On the other side of this divide was a family that had been grievously wronged, though they too, did not fully know that it was the time of their meteoric ascension.

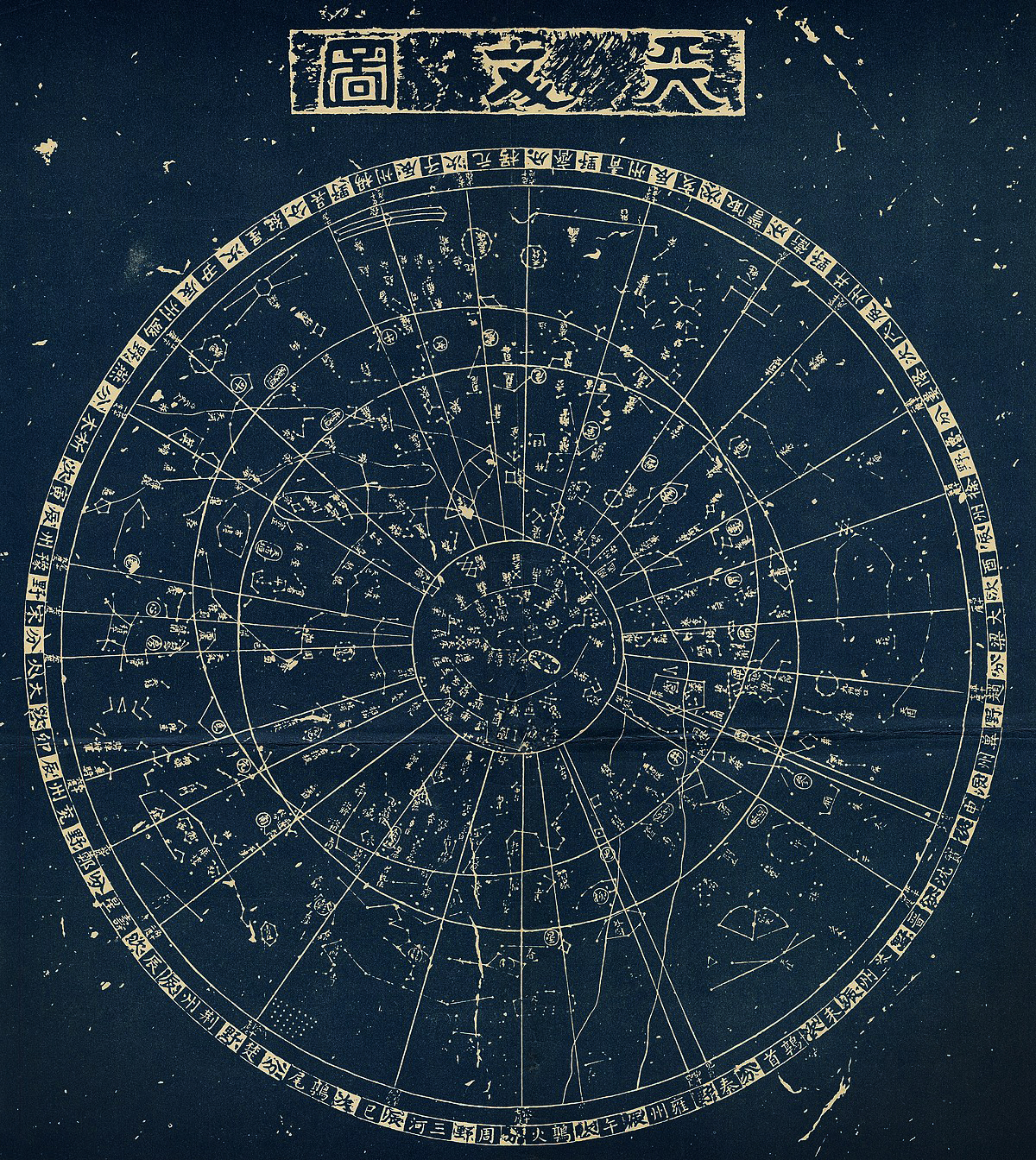

But an answer did came to these mortal men, and it was dramatic in the extreme: cosmically so. When these most dangerous lords of the west gathered, all they needed was to look up. And it would have impressed observers throughout the planet Earth. For on the evening of May 28th, 1059 BC, all 5 planets that was known to man all converged together in a straight row.

.jpg)

.jpg)

This was not missed even in some of the earliest chronicles of China, and in the ancient Bamboo Annals which documented the earliest recesses of Chinese history it was recorded that during the reign of Di Xin of Shang (it's last King,) 五星聚于房有大赤烏集于周社 "the five planets gathered in the Room 室 (Chinese Scorpio); in the vermillion bird clusters of the southern skies, there, 5 planets gathered and made it appear as if the great bird was clasping a jade scepter in its beak, the great vermillion bird alighted on the Zhou altar to the soil." Furthermore, that the row of these five planets continued to be visible for several days even after full darkness had fallen. For the watchers, it would appear that the Heavenly die had been cast for them. Now it was their time to cross their own Rubicon.

The Bamboo Annals explicitly mentions conjunctions of all five planets occurring before and after the Zhou conquest. Han-period texts mention the first conjunction as occurring in the 32nd year of the reign of the last Shang king, and when the patriarch of Zhou Ji Chang (the future King Wen) was 41 year old.

In the early 20th century, reflecting on his own brutal, changing era, the famous Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci once uttered this famous phrase during his long imprisonment under the Italian Fascists: “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.” The climactic aligning of all of the known planets stitched high on the heavens would be the exact spark that would lit the powder keg of this age. Under this fateful Heavenly sign would pour tens of thousands of marching soldiers, whose hearts would be filled with a new deadly purpose.

An aggrieved army braving a thousand traitor's death: Despite knowing each would be hunted down if they failed, they marched across the Mengjin ford, crossing the dire Rubicon. Swearing to avenge the wrongs done by Shang, all of their chariots gathered for the suicidal strike.

And as Gramsci described, of such transformative eras, something new and meteoric would be born in their treading wakes. Here, the 3,000 year governing pillar of Chinese political thought would be born, and it would last from this cusp of Hector and Achilles, all the way into the machine gun fires of the 20th and 21st century. Here the Mandate of Heaven was born, and with it, China.

TWILIGHT OF THE SHANG DYNASTY

Our story began in the twilight of the Shang dynasty. By 1059 BC the Shang had dominated what was central China's plains for over five centuries. Its fortune and control had waxed and waned, but despite all trials and tribulations, Shang power remained. Peerless Shang bronze were highly prized and imported by all its nearby neighbors- including its deadly rivals, and its chariot led war- machine was well experienced with fighting on all four cardinal directions. At one point or another, the Di of the north, Rong of the west, Yi of the east, and Man of the south all paid tribute to the great Shang kings, who stylized themselves as no less than Heaven empowered priest Kings. Yet here, the unmistakable precipice of their fall was revealed.

.jpg)

Here was the twilight of the Shang dynasty, though its great kings still professed to be great shamanic kings, beloved by Heaven, it was a reign of blood. Many key ministers were purged, and were tortured. This was corroborated historically, but the interpretation was less draconian, for King Di Xin rose during an era where Shang's power were already wilting from within, this meant he had many enemies from within. Thus his bloody purges were likely a natural attempt for the struggling regime to reassert its damaged primacy by wrangling back blocs of his disloyal vassals. Regardless of his motives, be they paranoia or legitimate corrective violence, both he and his dynasty will be defined by the enemies they made.

According to traditional accounts, the fall of the Shang dynasty could be pegged to its last calamitous king Di Xin's rule (called King Zhou of Shang, though it should be noted his posthumous moniker of "Zhou" 紂 ~ which ignominiously means a horse filthy crupper is actually totally another character than the "Zhou" 周 of his enemies. Both are also written and pronounced differently- thus for clarity sakes, we shall refer to him as King Di Xin in our narrative to avoid confusions.) The classical portrayal of Di Xin was that of an exemplary bad ruler, an archetype of a fallen and debauched King. However as we frame this story, we will also actively intersperse historical and archeological findings. And if they greatly contradicts that of the traditional (Zhou) narrative, we shall bring it to light here.

A FATEFUL IMPRISONMENT

Our story began with a cruel imprisonment. The paranoid Shang king Di Xin had broke with the façade of peace and protocol and- seeking blood, decisively went after one of his once most capable and highly favored vassal lords. Here, bad blood began between their two houses, and all things were set in motion. For only a few years ago, this lord had been one of king Di Xin's best ministers. He was also the father of a brood of hidden dragons. Going after this man will unleash a vengeance fueled war like no other for China's heartlands, led by none other than the imprisoned lord's wrathful children.

FATHER OF A BROOD OF DRAGONS

Born Ji Chang (姬昌), the count of the western region of Zhou (situated in what is today's Wei River Valley in Shaanxi) was a highly remarkable man. Once, he was one of Shang's most trusted vassals. Ancestrally having been married into the Shang royal clan, they had been fierce allies. His tribe had served the Shang in generations of military affairs, and they helped stomp out many of Shang's most ardent enemies. When Shang was weak, Zhou were a vital shield that parried the fatal blows of invading barbarians, such as the Guifang 鬼方 from the north (most likely ancestors of the future Rong people,) and at moments where the Shang regained their strength, the Zhou relentlessly fought as Shang's expeditionary vanguards and vanquished many enemy tribes that would do the Shang harm. However the count's great strings of victories would provoke great jealousy and fear from none other than the very Shang king he spent his prime protecting.

Shang (Red) and Zhou (Blue.) Count Ji Chang's domain resided in the western regions of the Wei River Valley (Blue), there lived his people, the Zhou tribes. There was ongoing debate both among ancient Chinese historians as well as modern historians whether they were truly completely Sinicized (mirroring that of the Shang of the Central Plains) or only partially, that though they were related to the Shang and are part of the larger Yellow River culture they were still only partially like the Shang. In the 3000 years hence this era the Wei River Valley in modern Shaanxi had been largely terraformed to be able to provide sustained agriculture but in ancient times the valley was more divided, and tribes in the area both farmed and for some also lived a semi- pastoral lifestyle.

Shang (Red) and Zhou (Blue.) Count Ji Chang's domain resided in the western regions of the Wei River Valley (Blue), there lived his people, the Zhou tribes. There was ongoing debate both among ancient Chinese historians as well as modern historians whether they were truly completely Sinicized (mirroring that of the Shang of the Central Plains) or only partially, that though they were related to the Shang and are part of the larger Yellow River culture they were still only partially like the Shang. In the 3000 years hence this era the Wei River Valley in modern Shaanxi had been largely terraformed to be able to provide sustained agriculture but in ancient times the valley was more divided, and tribes in the area both farmed and for some also lived a semi- pastoral lifestyle.

Culturally there were some noted differences between the two peoples' societies. In Shang, inheritance usually went to the youngest son, thus the newest born son often had precedence over his elders. It was a way for the procrastinating clan to keep birth out as large of a candidate pool for leadership as possible. And if the king dies often power shifted laterally back to his uncles and brothers. Women also had far larger roles in Shang societies, with great queen- consorts such as

Fu Hao and

Fu Jing leading whole armies as its generals. By contrast, the Zhou (at least traditionally believed) practiced primogenitor at this time. Which meant that the eldest son inherit the position of leadership. Zhou relationship between men and women were much more lopsided compared to the Shang. Also according to Zhou narratives, the Shang relied far more on slavery where as the Zhou less so- though modern historians cannot determine if this was in fact true.

THE RIGHT HAND OF THE KING

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

The bad blood began violently in the extreme. As previously related, despite having long served the Shang with his eldest son- a capable warrior and filial son in his own right, and having served as one of Shang's wisest ministers in court, count Ji eventually provoked the violence from his overlord. Though evidence are scant as to the real cause of their fallout, traditionally Di Xin was demonized as having sacrilegiously written lurid and pornographic poems "dedicated" to the goddess Nüwa and that she~ in her wrath sent out a scourge that eventually caused the downfall of the Shang dynasty.

This of course was little more than propaganda, and a narrative shorthand for the commoners to imagine their toppled kings as having been degenerate, transgressive, and already utterly unbecoming of their sacred positions. A much more likely scenario was that the the count of Zhou had proven to be too dangerous to be allowed to continue to rise.

.jpg)

That he was both militarily dangerous on the battlefield as well as highly influential right within the Shang court. It should be also noted that in Zhou's heartland domains, they were also ascending, and many tribes swore fealty to the Zhou in the west. In geopolitical terms the ascension of the count represented a perfect storm of compounding threat for king Di Xin and his position as king. That if a fateful day came where the ambitious count decide to coup Di, there would be nothing to stop that ploy. Fortunately for King Di Xin and to the extreme ill- fortune of count Ji, someone was going try to uproot the Ji clan utterly from the Shang court. She was none other than one of China's most reviled femme-fatales. And as the narrative would have it, the very scourge, the offended goddess Nüwa sent down to torment the mortal world.

FATALE

Lady Fox: Consort Daji's beauty was such that not only could she bewitch kings but destroy the very foundations of once- noble kingdoms. All was well until she came along...Or so they would have you believe. She was the Zhou's perfect scapegoat. In fact they have blacked her so much that even today she is synonymous with succubus in China and

also in the world beyond.

King Di Xin had once been a wise and virtuous ruler...until he met her. One thing that even the harshest critic of Consort Daji would not contest was that she was incomparably, and ravishingly beautiful, so beautiful that she bewitched an otherwise clear headed sovereign and sent his dynasty to hell. Shang practiced polygamy for its kings- (largely for diplomatic reasons) whenever a new tribe forged relation with the Shang dynasty often they would send him a wife as their envoy. At the height of the Shang dynasty- including the reign of its great martial king Wu Ding's reign, he had at least 64 wives- including the famous warrior queen Fu Hao and most of them were princesses from his allied vassals.

Fateful couple. Daji and Di Xin were one of the classical infamous couplings in Chinese history, along with King You of Zhou and Bao Si, and also the famed Lu Bu and legendary Diao Chan (even that of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang and Yang Guifei.) Highly passionate pairings, they left destruction and ruin in their wake, yet their fatal love was such a vain blaze that history refused to forget.

Daji was one of these illustrious noble ladies, and was descended from the powerful Yousu 有蘇 clan, another one of the most powerful clans in the Shang realm. After Di Xin subdued them in conquest they tributed him with cattle, sheep, and the person of their well- made daughter. It was said that before Di Xin met his new wife Daji, he was a talented and promising young conqueror who was erudite of mind and was able to resoundingly win all arguments, he was also exceedingly well gifted with brawn, so much that he was able to subdue great beasts with bare hands and outfight legions of men. Blessed with handsome looks and youthful ardor, he tried to hire the most talented within the realm to be in his court and he attended court dutifully. But after he became maddeningly enamored with Daji, he became a cruel and sadistic tyrant.

BLOOD OF THE INNOCENT

For many decades, the Count of Zhou Ji Chang's son and crown prince Bo Yikao was his pride and joy. A handsome boy who was both a filial son, a respected warrior, and a talented musician. It was said that his music aroused a dark possessive passion within the lustful Daji.

After marrying Daji, king Di Xin became extremely attached to her, so much so that she inflamed and emboldened many of his worst personality traits. Di Xin already showed signs of paranoia in his early reign, including infamously kicking out his elder half brother for criticizing him (and being a percieved threat to his power.) This bloodthirsty streak was further inflamed by Daji's encouragement. Returning to our earlier point where we established the Count of Zhou's great sway in the Shang court and his strings of meteoric victories for Shang, it was here, under Daji's influence that the once- wise and promising Di Xin fully went after his able Count.

Music: [in F Guzheng Cover]

In 1057 BC, Without warning, the Count of Zhou was arrested, and his's crown prince Bo Yikao was brutally killed by the Shang (alternatively that he died during his father's captivity) and Daji tried to force the imprisoned Ji Chang to relinquish many of his sworn vassals from obedience to the Zhou in the West. When Ji Chang protested he was tortured and left to rot

in the royal prison cells at Youli 羑里. Both Daji and Di Xin contemplated executing Ji Chang by death of thousand cuts, but it was said that most of the Shang court- who had long understood that Ji Chang was a man of talent and had diligently governed with honor interceded on his behalf and prevented him from this grim ignominious death.

Despite this, Ji Chang languished in his cellar. Meanwhile, trouble had erupted in the Zhou domains in the west. With Shang's blessing, many of the previous vassals that sworn loyalty to the Zhou, now with Shang backing, abandoned the Zhou and began to check against the Zhou from many directions. Within the blink of an eye, Zhou was strung out to bleed. But this was only the perverse beginning.

Soon Di Xin's reign would veer maddeningly into full despotism. He frequently executed ministers who dared to oppose his decisions and became aloof of their counsel. Instead, he retreated into spending most of his time with Daji and began to lead a bacchanal and pornographic lifestyle, according to later Zhou histories he hosted wild orgies with his circle of favorites, and frequently wrote pornographic poems that mocked the gods. At his vast Lutai or Deer Terrace Palace, the king was reported to have indulged in "Meat Forest and Lake of Wine." There he filled a vast pond- lake of the palace all with wine and decorated the palace garden's forests with hanging meat. There he hosted lavish orgies and- when a dark mood tickled him, saw violent tortures and executions along with Daji. In fact, Di Xin's loss of control to Daji's influence was such that it was written: "whoever Daji liked, Di Xin promoted, and whoever Daji hated, Di Xin would have them executed."

Daji herself not only delighted in instigating and enjoying many executions, but she was recorded to be very creative in her sadism too. In the case of the aforementioned death of the Count of Zhou's crown prince Bo Yikao, a version had it that Daji-

like Potiphar's wife became very enamored of him, but when he rebuffed her lecherous advances, she became extremely jealous and promptly had him executed by thousand cuts. Most of all, it was recorded that she invented an extremely insidious torture device called Bronze Toaster (炮烙). The "Toaster" is described as a bronze cylinder covered with oil heated like a furnace with charcoal beneath until its sides were extremely hot. An accused victim was forced to walk on top of the slowly heating cylinder, and he was forced to shift his feet in order to not burn. The sizzling oily surface made it difficult for the victim to maintain their balance, and if the victim fell into the charcoal below, they would be fried to death. Later retelling of Daji's life imagined that she was actually an evil

9 tailed fox spirit, sent by the angry goddess Nuwa to punish the house of Shang.

Music: The Greatest Change

A CRUSIBLE OF CHANGE: FROM BOYS TO MEN

Ji Fa and Ji Dan were the 2nd and 4th sons of the imprisoned Count of Zhou. Though they have never anticipated their sudden mantle of leadership. Fate in its full cruelty thrusted them fully in the reins of power. Despite the awfulness of this sudden twist, both not only managed to save their state in its darkest hour but became 2 of the greatest cultural heroes in Chinese history.

Perhaps Zhou should be judged in the absence of its once- indispensable lord. For while he was imprisoned, in the dreaded power vacuum, 2 of his sons became even greater than he ever was. They would one day became King Wu of Zhou- the founding progenitor of the Zhou kingdom, and Duke Wen of Zhou, one of the most revered of Chinese paragons.

Wén 文 "civil" and wǔ 武 "martial" - was a critical concept in Chinese philosophy and political culture describing opposition and complementary spheres of civil ① and military ② arenas of government. The saying 文武両道: or "Civil and martial both ways" or "Civil and martial mastery" describes the essential need for the ruler to staff his regime with both of these types of men.

Thus many years would pass in this manner. But despite this harrowing downspiral, others have not been idle. Though the vulnerable Zhou was deprived of its patriarch and its crown prince, it fiercely held on in the west despite being checked by many Shang backed proxies. It was during this time that 2 of the elder Count of Zhou's sons raised to the occasion and held up their beleaguered state at its darkest hour. Because of the imprisonment of the clan's leader, power fell on Count Ji Chang's surviving eldest son (second son) Ji Fa 姬發, and fourth son Ji Dan 姬旦, both of them would became 2 of the greatest cultural heroes of China. The Count of Zhou had 16 sons, and 11 of them born to his main wife, of these sons, Ji Fa and Ji Dan inherited two aspects of his brilliance separately. Athletic and charismatic, Ji Fan soon took over the mantle of the clan patriarch and soon proved himself as a feared and respected warrior. At the same time, in matters of statecraft, the fourth son Ji Dan proved himself to be a peerless statesman and scholar. Astute in judgement and a peerless orator, he soon staffed the troubled Zhou court with wise ministers and trusted warrior generals. The two of them would one day lead the dreadfully provoked Zhou armies in the west to utterly crush the Shang into shards.

During this time the imprisoned Count of Zhou had not been idle either. Despite having his body caged, it was traditionally asserted during this period he spent his captivity writing and pondering over ancient puzzles and mysteries. He became close friends with nearly all of the incarcerated prisoners and learned from them that they worried he would loose his mind here if he was imprisoned too long. Previously, the Shang court had also had an able minister just like him, who had also valiantly and ably served the Shang for some 20 years. But that once- great man, through being exposed to Di Xin's degeneracy and cruelty had lost his mind and went crazy.

%201.jpg)

Fearing the possibility of a permanent imprisonment, they advised that the Count should concede some of his lands and holdings, just so he could trade back his freedom and return to his power base. Though he knew that even if released, Di Xin would never stop trying to chip away at Zhou, he still chose to relent to some of Daji and Di Xin's demands so he would be free. After all, the imprisonment did start to irrevocably break his mind, still- he made the best of his long imprisonment. During this period of captivity, it was traditionally attributed that the Count wrote the famous

I- Ching, or the "Book of Changes," one of the oldest book of Chinese divination.

At last, the Count relented to Shang pressure. He vowed to break up pieces of the Zhou holdings and render tribute to Di Xin with cattle, sheep, women, and treasures. After having given a piece of adjoining Zhou land to the Shang, Di Xin, now satisfied, allowed the haggard and seemingly broken man to limp back to Zhou. Despite bidding his fellow prisoners farewell, and despite bidding his Shang overlord that he would remain his most obedient vassal. The half broken man- a man who was once the right hand of the Shang king and pillar of the Shang state would nurse a deep seated grudge at his outrageous treatment. He vowed to not only return, but return as an independent king, at the head of a mighty, avenging army.

THE WANDERINGS OF THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING

When the Count of Zhou returned to his home fief, he saw a well- run country. During the long years of his imprisonment both Ji Fa and Ji Dan did not disappoint him, instead- despite territorial concessions and the emptying of its treasury to ransom its patriarch back, the Count's sons had transformed the state to be both militarily formidable as well as financially self sufficient. Instead, the doubtlessly proud patriarch allowed the state to be continued to be largely ran by his talented sons. Ji Fa was already a well- respected clan leader (and would in total lead the clan well for some 11 years) so while his son ably ruled with Ji Dan, the father chose to venture the realm in order to gather all the able men of the realm he could find under his roof. Here is where one of the most remarkable encounters in Chinese history happened.

Before going hunting, Count of Zhou consulted his chief scribe to perform divination in order to discover if his mission for minding a great man would be successful. The divinations revealed that, "While hunting on the north bank of the Wei river you will get a great catch. It will not be any form of dragon, nor a tiger or great bear. According to the signs, you will find a duke or marquis there whom Heaven has sent to be your teacher. If employed as your assistant, you will flourish and the benefits will extend to three generations of Zhou Kings.' " Mindful of this auspicious prediction, the Count observed a vegetarian diet for three days in order to spiritually purify himself for the meeting.

While on the hunt, King Wen encountered an old fisherman fishing on a grass mat. When the Count of Zhou met this fisherman, at first sight he felt that this was an unusual old man, because he was fishing with a straight hook. Puzzled, though still fully courteous, he asked what type of fish the man would wish to catch with a straight hook, and the old man responded that he would catch a King. For in actuality, this fisherman was none other than the once famous "gone- Mad" minister of Shang. The very same one who had served the Shang for 20 years as an able general and minister, and then feigned madness in order to escape from court- Jiang Ziya. He was- in short the Sun Tzu of this age, combined with a hefty doses of Lao Tzu.

Delighted that such a legendarily peerless sage and strategist had chosen to reveal himself to him, the Count eagerly conversed with him. They talked in length, and over many hours and many days talked of military stratagems, statecraft, and governance. The subsequent conversation between Jiang Ziya and the Count forms the basis of the text in the

Six Secret Teachings. In appreciation of both the measure of the Count's astute character and his polite deference. The wise Jiang Ziya happily casted his lot with the rebellion- minded man who would be King. The couching tiger had found his hidden dragon.

The Count took Jiang Ziya in his coach to the court and appointed him prime minister and gave him the title Jiang Taigong Wang ("The Great Duke's Hope", or "The expected of the Great Duke") in reference to a prophetic dream the Count's grandfather, had had many years before about a Messianic ally who would aid his house. This was later shortened to Jiang Taigong. The Count's heir Ji Fa married Jiang Ziya's daughter Yi Jiang, who would bore him several sons.

As an aside, Jiang's clan would be extremely influential for the next half millennium. For Jiang Ziya's line would found the Duchy of Qi- one of the most powerful of the Zhou- and Spring and Autumn states. For centuries they would not only be frequently the future Zhou King's wives- but during the later Spring and Autumn period, would birth the

first of the era's Five Great Hegemons: Duke Huan of Qi. Nearly a millennium later, although displaced by another bloodline, the Kingdom (in the Warring States era) that Jiang Ziya had created would survive as the very last of the 6 remaining kingdoms that the First Emperor of China vanquished in 221 BC.

RISEN KING WEN UNIFIES THE WEST

After several years of searching, and after he had staffed his court with many able generals and ministers, the Count of Zhou revealed his ambitions. In the first year of his return, he settled a land dispute between the 2 nearby states of Yu and Rui, earning greater recognition among the western lords. It is by this point that some nobles began calling him "king." And we shall now call him King Wen of Zhou.

With his Prime Minister Jiang Ziya's astute advice, King Wen soon began a series of punitive campaigns against barbarians, former disloyal vassals, and Zhou's archrivals, he sent campaigns westward against Quanrong (Proto- Tibetans,) the states of Mixu who was one of the rival local powers in the west, Li- a Shang proxy and ally in the region, Han, E, and defeated Zhou's archrival state of Chong. After taking Chong, the Chong capital at Fengyi was converted into the new Zhou capital.

It was after this flurry of campaigns, outreaches, and subjugations that on May 28th, 1059 BC, when the Count was 41 years old, all 5 planets that was known to man all converged together in a straight row in the southern sky.

There King Wen greatly built up Fengyi (now Huxian, Shaanxi Province), and swept his forces east along the shores of the Yangtze River, Han River, and the watershed at the western bend of the Yellow River. This last part was critical, for having done this, Zhou now was once again directly bordering with the Shang and separated only by the shallow Mengjin river ford as their border. By either cowing or outright conquest, King Wen forcefully consolidated his hold in the west over the many western states under the Zhou banner.

It was recorded by later Zhou historians that by then King Wen had obtained about two thirds of the whole kingdom (of what was Zhou's royal heartland) either as direct possessions or sworn allies. Now the heartland of Shang was only a few ride's away and directly within the range of a committed Zhou strike. However, before King Wen was able to finalize his total control over the west and cross this deadly Rubicon, he died in 1056 BC. Traditions vary as to the manner of his death. It was possible that he succumbed to his old age, though it was also likely that he fell in battle or succumbed to a fatal wound during campaign at this time.

.png)

Music: Leaves from the Vine

Thus passed the great King of the west at the height of his meteoric resurgence. It was recorded that before King Wen passed, he instructed his son Ji Fa to vanquish Shang with expediency as soon as possible. Although in many other states in world history, such untimely passing of a faction's patriarch would have devastating political consequences- even leading to a piranha's feeding frenzy from their nearby neighbor states. The late King Wen would, by contrast have comparatively few such worries. At his death, he left his children a court full of loyal and able ministers, and his children were his brood of hidden dragons.

THE WEST ASSEMBLES FOR WAR

The wake of the great King of the west's death would be presided over a dizzying list of the most dangerous men in the realm. For those who now swore to the young new King Ji Fa- (future King Wu of Zhou) in fealty were a star- studded list of characters. Nearly all of these names will be a founding member of Zhou's great houses, and in the ensuing Spring and Autumn period some 300 years later, their descendants would even become great kings in their own rights. Here we shall find the ancestors of

Qi,

Jin,

Chu, (three of the 5 Hegemons of the Spring and Autumn period) +

Lu,

Yan, and many more lesser states etc all swore to the Zhou throne here. Several of such states, such as Qi and Yan would endure for nearly 900 years all the way until the wars of unification of China by the First Emperor.

Traditional accounts have the newly crowned King Wu as being only 30 at this year. At the age of 19 the mantle of the Ji clan was placed on his heavy shoulders and he would lead as the patriarch of the house for the next 11 years.

Despite his father's deathbed bidding, the newly enthroned King Wu did not hasten into war ("Wu" meaning "Martial" was bestowed after his death for his martial warrior prowess, but for the sake of modern clarity we shall refer to him by this moniker.) Instead he took the advice from Jiang Ziya and used the next few years in expanding the pool of his banner men and finished his father's ambition of fully consolidating Zhou's hold in the west.

Zhou's consolidation efforts did not went unnoticed from the Shang, and for their part the Shang did try to preemptively goad Zhou into a disadvantageous war. For despite his father's departure from the Shang court, his other family still remained inside Shang's hold, and Bi Gan, King Wu's uncle was murdered by Daji. Reportedly he received an unfortunate end at Daji's hands by having his heart cut out and examined to determine if the ancient saying of "a good man's heart has seven apertures" was true. However, despite being dreadfully provoked by this killing. King Wu endured and bid his time.

In 1048 BC, King Wu- Ji Fa marched down to the Shang Zhou border at the Mengjin ford of the Yellow River and met with more than 800 dukes of various states in the west. He constructed an ancestral tablet naming his father officially as King Wen then placed it on a chariot in the middle of the host; However, still considering the timing unpropitious, he did not yet attack Shang and continued to bid his time. And then, on 1046BC, the planets aligned again, and Jupiter returned to the exact location of the Vermillion Bird in early 1046. That spring, King Wu ordered an all out muster of all of his banner lords.

.jpg)

All of the Zhou's western vassals had gathered for the occasion and the timing could not have been more perfect. That year, Shang was caught in a regional war against one of its southeastern neighbors. Thinking that the Zhou were not a serious threat, Shang king Di Xin then ordered most of Shang's crack troops eastward against barbarians there. Concurring with Jiang Ziya and his brother Ji Dan that the time had come, (and again blessed with the joining of the planets) King Wu gathered a massive host of some total of 50,000 soldiers, the vanguard was headed by 300 chariots supported by 3,000 crack armored guards in the west and

made his speech.

Mù shì 牧誓 or "Oath" proclamation, recorded that:

「嗟!我友邦冢君、御事、司徒、司马、司空,亚旅、师氏,千夫长、百夫长,及庸,蜀、羌、髳、微、卢、彭、濮人。称尔戈,比尔干,立尔矛,予其誓。」

"Lo, I have the loyal ministers (titles) arrayed: Yushi, Situ, Sima, Sikong, Ya lu, Shi shi, Qianfu Chang, Baifu Chang had gathered with their banners. I also have the tribes of Ji yong, Shu, Qiang, Mao, Wei, Lu, Peng, Pu People at my command. Raise your daggers, line up your shields, bristle your spears, I will swear."

「今商王受惟妇言是用,昏弃厥肆祀弗答,昏弃厥遗王父母弟不迪,乃惟四方之多罪逋逃,是崇是长,是信是使,是以为大夫卿士。俾暴虐于百姓,以奸宄于商邑。今予发惟恭行天之罚。」

"The Shang King today only accepts the effete counsel of his Consort, dazed, he ignores his sacred duties in sacrifice to the gods and ancestors, he ignores the myriad of wise patriot's counsel (King's murdered uncle Bi Gan, and others like Jizi and Weiziqi) instead, the court was staffed with fugitive sinners so they oppress the common people and tyrannize the Shang cities. Thus the country is in turmoil. Today in obedience I solemnly swear that shall visit Heaven's punishment upon them."

This speech was almost certainly scripted and sculpted by King Wu's brother Ji Dan- later the famous Duke Wen of Zhou. The last clear reference that the King would mete out punishment "for Heaven" was the flagship idea of the wise Duke. For he was none less than the father of the concept of the Mandate of Heaven. Or alternatively more compatible here "Heaven's Command."

「今日之事,不愆于六步、七步,乃止齐焉。勖哉夫子!不愆于四伐、五伐、六伐、七伐,乃止齐焉。勖哉夫子!尚桓桓如虎、如貔、如熊、如罴,于商郊弗迓克奔,以役西土,勖哉夫子!尔所弗勖,其于尔躬有戮!」

In today's war, when marching, no more than six or seven steps, you must stop and reform up. Braves, you must do your utmost! When plunging into forays, no more than four Three times, five times, six times, seven times, you have to stop and reform up. Generals! I hope you are resplendent in your fearlessness, that you will be like tigers, pi xiu (winged lions), bears, and scorpions. to help our Zhou Kingdom. Do your utmost, soldiers! If you don't rise to your occasion, you will only punish yourself!"

With this, a century after the Trojan War and one century before King David, the zealous Zhou host raced eastward from their nestled valleys and crossed the fateful Mengjin Ford. This would be the Rubicon moment for the Zhou army, as from this point on it would be a suicidal march for each of the soldiers if they would fail in these hostile lands.

But in their hearts, the warriors would be branded the idea that they were sanctioned by heaven itself. Now that the ideological battle has been won, it was up to the King to do his part with his warrior's hand.

CROSSING THE MENGJIN FORD

Zhou's sudden attack from the west in full force with some 50,000 soldiers completely caught the Shang court off guard. After realizing it was too late to recall the majority of their troops in the east, Di Xin cobbled all that he could find within his kingdom and mustered them to the west of his capital at Yin. The concentrated Zhou attack was such that all the Shang outposts and minor local resistances along the were were blown asunder.

Desperate to rally all that he can to defend his capital, Di Xin resorted to massed forced conscription of Shang's slaves and armed them for the upcoming battle. Thus for the Shang side, their forces would be consisted of a depleted rank of their core of trusted warriors, a large section of unhappy slave conscripts, and a top echelon of dedicated professional loyal generals and retainers from the capital that Di Xin was able to recall.

Later historians such as Sima Qian would put up laughable figures for the Shang and state that they were able to rally some 500,000+ soldiers (with slaves consisting of some 170,000,) although it was definitely not that much. It was more likely that Sima Qian was working with his contemporary Han and late Warring States figures and also from a particularly gory description of the battlefield after the bloodletting (which we will reexamine soon.) In most modern estimated likelihood, the Shang either scrounged enough soldiers to match the coming Zhou host of 50,000 or that they had a larger contingent of some 70,000 strong.

However, despite this, the army that opposed them was commanded ironically by men who had spent much of their times once- defending the Shang from the inside and knew all of its defensive networks (Jiang Yiza etc.) On the Zhou side, it was an army that was especially forged and tailored for this campaign. Now they came, full with vengeance in heart, with the force of a falling headsman's axe, it caught the Shang army right outside the royal capital. On the morning of March 20th, 1046BC (Date, Pankenier) on the western wilderness of Mu outside of the Shang capital of Yin which was long used for grazing- the Zhou army found the massive Shang host.

THE WILDERNESS OF MU

Records regarding the details of the battle are scarce, but from the description of the Zhou tactics employed in this battle it would seem that the slightly numerically superior Shang forces- personally led by king Di Xin himself extended the Shang battle lines (since many of its troops are slaves with low morale) so as to avoid being flanked by the renowned Zhou chariotry. Likely at key hinges were deployed trusted veteran Shang commanders with their band of warrior guards. The Shang's flank was largely secure because the capital of Yin covered their rear. The Shang's plan consisted of absorbing the Zhou blows and then use its superior numbers to whittle down the Zhou until they suffer greater losses in the meatgrinder and break.

By contrast, the Zhou, seeing this, chose instead to fully take advantage of the over-extended Shang lines. Since because they are so widely laid out, the forces on the far fringe of one side of the battle line cannot come to the rescue of the other parts. Instead, the Zhou forces formed a large recoiled vanguard column with their chariots. The 300 crack chariots gathered closely and coalesced around the personal command of King Wu. They would come as a sledgehammer.

King Wu's decisive chariot charge caused a gaping wound in the Shang line and a major section of the Shang line faltered. According to the custom of contemporary chariot tactics, ranks of armored foot soldiers that were personally bound to their chariot- riding armored lords soon raced in and exploited the gap. The Zhou chariot did not waste their time and quickly began to- with coordination fan out and exploit the widening wound. The desperate Shang then tried to rally mobs of its soldiers and surround the Zhou vanguard, but the generally better trained Zhou overwhelmed many that came their way. When the Zhou forces reached many of the Shang slave- conscripts, either through prior- conspiracy, or a previously agreed gesture among the slaves, many bands of slaves simply collectively tilted their spears downward or stabbed into the earth as a sign they don't want to oppose the Zhou forces. Instead, many of them openly joined the Zhou forces and threw themselves on their former enslavers.

-.jpg)

Soon some thousands of Shang slaves joined the Zhou and turned on the Shang forces. With this turn, the Shang army began to waver. One person that did took flight from the field of slaughter was the Shang king Di Xin himself, who- either through his personal cowardice or more likely at the urging of his generals seeing their imminent defeat climbed up his war chariot and quit the field racing back to his palace inside Yin. However, this was not the reaction of many remaining professional Shang loyalist warriors. Instead, they hardened themselves and bitterly resisted all Zhou advances. When the initial battle lines descended into armored slog between mobs, they held their ground and did not gave ground, nearly all of them perished where they stood with their whole companies of followers.

The Battle of Muye was an extremely bloody affair and the battle continued for nearly a day. But at the end of the day, the more determined Zhou forces still prevailed, nearly all of the Shang loyalists were slaughtered to the last. In fact, it was said that at the end of the day the field were overflowing with so much blood that a log could made to float in the knee high blood field. In the famous Shijing, or Classics of Poetry/ or Book of Songs- collected in the Han dynasty but mostly consisted of poems written in the Western Zhou dynasty (right after this time) was a poem that gave some scintillating images related to this battle: Book of Poems: (poem 236), as translated by the 19th century Scottish Sinologist James Legge:

殷商之旅、 The troops of Yin-Shang,

其会如林。Were collected like a forest,

矢于牧野、维予侯兴。And marshalled in the wilderness of Mu.

上帝临女、'God is with you, ' [said Jiang Ziya to the king],

无贰尔心。'Have no doubts in your heart. '

牧野洋洋、The wilderness of Mu spread out extensively ;

檀车煌煌、Bright shone the chariots of sandal ;

驷騵彭彭。The teams of bays, black-maned and white-bellied, galloped along ;

维师尚父、The grand-master [Jiang Ziya]

时维鹰扬、Was like an eagle on the wing,

凉彼武王、Assisting king Wu,

肆伐大商。Who at one onset smote the great Shang.

会朝清明。That morning's encounter was followed by a clear bright [day].

Shijing, or the Book of Poetry is considered by modern scholarship to be the

oldest book from East Asia, and many of its earliest arranged poems dates to the founding of the Zhou dynasty (11 century BCE) and consisted of many odes and praises of its rulers and sages.

A PYRE OF VANITY

Unfortunately for Di Xin, that bright day would be his last. He would will it so. When he raced back from the gory field at Mu, Di Xin returned to his massive palace at the Deer Terrace Palace. There, unable to cope with his crushing defeat and unable find any ways to stop the inexorable Zhou victors, he raced across the many rooms of his massive palace and gathered all the priceless treasures that were stored within each room. Then, after surrounding himself with all of his expensive worldly possessions, he forced all of the wives that he could find to kill themselves beside him.

Debaucherous excess and destruction, Like the famous French Romantic Era painting "Death of Sardanapallus" by Eugene Delacroix- where the supposed doomed Assyrian King Sardanapallus committed suicide by having all of his prized horses and concubines slaughtered- in addition of having all of his treasures piled up for his funeral pyre, the last king of Shang hastily retreated back to his palace after his defeat at Muye. There he gathered all of his treasures together, forced his wives to commit suicide beside him, and lit the palace ablaze as a final act of gluttonous spite.

After that, he draped himself on a robe effulgent with jade jewels and set himself and his own palace ablaze in a final possessive act of spite. And for miles, the citizens of the great capital of Yin was able to see the massive fireball of the once- great palace burn.

Flushed with victory, the victorious Zhou army soon came in Di Xin's wake. When King Wu entered Yin he ordered the massive granary inside the city to be opened to feed the starving population, the King then freed all of the slaves that had joined his army, and ordered that the Shang royal prison at Youli (where his father had once- been held) be opened and its political prisoners freed. There was also an unexpected streak of clemency: Di Xin's relatives- his elder brothers, and his son were not harmed. Most- if not all of the Shang ministers they found were pardoned and were allowed to retain their positions. It was reportedly at the Deer Terrace Palace that the Zhou soldiers found Daji as well.

King Wu then mulled over the fate of the vicious beauty. But his father- in- law Jiang Ziya advised that such a woman cannot be spared. Heeding this, King Wu beheaded Daji with his

great battle axe (Yue) and also posthumously beheaded Di Xin's head from his body. After this, he displayed the Shang King's head and had it hung on a tall white flag. By contrast, the severed head of Daji and two wives and concubines were publicly displayed on red flags, together, these heads were sent back to the homeland of the Zhou ancestral temple to ameliorate and placate the wronged Zhou spirits.

There, at the foot of the burning Deer Terrace Palace, the Shang dynasty ended, and Zhou attained its climactic victory over the Shang.

CLASSICAL CHINA WAS BORN

The full establishment of the Zhou dynasty at the head of China was a major historical milestone. For in here, many things were born that would continue for some thousands of years. First, in the temporal arena. The decisive Zhou victory allowed King Wu to directly rule most of the Shang lands. Second was that King Wu used this opportunity to give out key domains in what was central China in the Shang heartlands to 16 of his brothers. It was here in this spoils giving- that feudal China was born, and for nearly a thousand years after his battle until the reunification of China under the first Emperor, China would be ruled by a vast hierarchy of lords who ruled their local domains essentially like minor kingdoms.

HORIZONTAL AND VERTICLE DIVISIONS

Vertically, the earliest framework of China's feudal hierarchy was created (Top.) Under the King, large tracks of Zhou China would be autonomously administrated by a caste of dukes, who would then govern their locality with able ministers, they would manage local blood- nobles. Underneath this lordly hierarchy would be the "Shi" 士, a caste of knightly warrior- retainers who would be tasked with managing the local region. In later times this class would become a class of scribes and scholars, and it was this class that many of China's greatest philosophers would be born from. Under them you have the vast peasantry.

Horizontal and Vertical divisions: Horizontally, King Wu- (under the guidance of his wise brother Duke Wen) divided much of what was the Shang heartlands under the command of many of his 16 younger brothers. Inheriting Shang's geopolitical realities as a plains dwelling state surrounded on four sides by myriad of barbarians. The Zhou now tried to cultivate a common culture within. Duke Wen strongly argued that the older Shang kings were indeed wise and favored by Heaven, and were men of virtue, but that it was the actions of the last Shang King that drove the Heavens (and the aligning stars) to unseat an illegitimate king.

This does not mean that he fully stripped the Shang old guard of power either, rather, he did not blame Di Xin's crown prince Wu Geng (who had earlier defected to Zhou due to his father's tyrannical reign) nor Di Xin's royal brothers. King Wu even assigned the former Shang capital- and metropolis of Yin to be directly administered by Di Xin's crown prince. Though in order to keep him in check, King Wu placed 3 of his younger brothers' territories right around Wu Geng's so as to keep a watch over the former Shang capital lest a revanchist revolt break out.

THE SOUL OF CHINA FORGED

Political map right after the Zhou victory at Muye. After the decisive Zhou victory, King Wu swiftly positioned many of his 16 brothers and half brothers as the head of many of the key sectors in the Shang heartlands. However he did not follow up with victory with a purge of the Shang royal leadership and its loyalists. He even allowed the crown prince of the fallen King Di Xin to retain his ancestral Shang capital at Yin and retain it as his own domain. Though in order to ensure that he does not rebel, King Wu eventually positioned 3 of his younger brothers around Yin as its "3 Guards."

The most important change that this revolution imparted- however, was more intellectual than merely temporal. For it was in this war that the idea of Mandate of Heaven- strongly insisted by Duke Wen's persuasion truly found purchase. For the next 3000 years, Chinese civil and political thought would largely revolve around the subject of legitimacy and correct political form (propriety.) By extension, because the Zhou framed that the amorphous force of Heaven has a distinct preference for a set of correct actions, proper behavior- propriety, politeness, and adherence to proper conduct became a key~ almost Skinner's Box cultural reaction to this interpretation of Heaven's will.

With this in mind it is not difficult to now understand why so much of Confucianism emphasized (actually reemphasized- since Confucius himself was by his eager admission a fan of Duke Wen as a peerless cultural hero) proper behavior, correct conduct, speech, and knowing one's station. After all, if men don't behave, Heaven just might topple them. It was here that we find the root of East Asian society's some times inflated adherence to polite optics, reverence to superiors, and more collectivist preference for social cohesion.

A STORY OF VICE AND VIRTUES/ A STORY OF ILLEGITIMACY

What stuck more in people's minds, perhaps greatly outlasting Duke Wen's original intent, was how long this concept of the Mandate of Heaven lasted well after the Zhou. And it could be argued that post- dynastic China of 20th and 21st centuries are still affected by this culturally ingrained outlook.

Not to mention the entire narrative is framed in such a well packaged story. A heaven- blessed war of destiny, of stock- heroic characters, villains. Composed right at the times of the Trojan War and Biblical Kings.

The genius of Zhou's framing (no less genius in pointing to an objectively miraculous aligning of all the known planets on Heavens itself) was that so much of Zhou's retelling of their propaganda, nearly 2/3 of their story was almost in 2nd person and depended on the internalization of the listener. By the time this origin story was told and retold each of this story's contemporary listener WOULD have personally already seen and felt the buildup laid out in this story, they've already with their own eyes seen or had heard the Shang king purge his ministers, letting the country into ruin, confide only with his Consort, and the Zhou army only shows up in the last chapter of this story, and that was framed as a liberation. This subtle propaganda was genius, because much of the first 2/3 of the story was framed with objective observations and stagings that could be internalized by each of the average Shang listeners, after all, who

would try to debate aligning of all the known planets on the heavens? and it was only the last part that the Zhou held the listener's hand and insisted it was their Heaven- sanctioned liberation.

.png)

During the Ming dynasty this same story was famously retold in mythical terms. And many of the figures that we have covered either ended up becoming Gods or had divine and fiendish interventions during this whole affair. It was in this retelling- called "Investiture of the Gods" (which many modern Wuxia and fantasy novels are based on) that Daji was named as having been a nine-tailed fox spirit all along. The earliest mention of Nine-tailed fox is the Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), compiled from the Warring States period(475 BC–221 BC) to the Western Han period. This succubus archetype would permeate in much of East Asia's literary culture and would be recognized as Kitsune (lit. "Fox" in Japanese) during the Heian era and a powerful incarnation would also appear in modern animes such as Naruto.

And who could blame it? It was a great exciting story, for lovers of Biblical chapters and George R R Martin sagas, was it not interesting that this ancient Chinese story from the world's time of legends had all the familiar archetypes of Jezebels, Ahabs, and Jehus? Or scenes almost lifted straight from GRRM's

Robert's Rebellion, and Robb Stark's northern rebellion? A tale with clearly defined good guys and bad guys, so much so that even modern scholars cannot truly separate just how good or how evil these depicted otherwise historical characters truly were. Least of all because we, a vital part of us need them to be that to flavor the story. Unfortunately, right when it appeared that- at least for the newly consecrated Zhou that they got their happy ending, everything fell apart. Only 3 years after his great victory at Muye, King Wu suddenly died, and the great house of card that both King Wu and Duke Wen carefully built came crashing down.

THINGS ALL FALL APART: A CONFLAGERATION

Suddenly, the 33 (or 34) year old monarch died. The timing of King Wu's death could not have happened at a worse time, for his crown prince was only a young child still in his minority. Sensing this opportunity, the newly conquered Zhou realm exploded in a realm wide conflagration of rebellion, pockets of Shang loyalists, rebellious Zhou Dukes with their massive armies, and even fierce tribes from the east that the Zhou have never encountered all opportunistically joined in this conflagration against Zhou rule.

Music: The Eternal Empire (Drums)

Against this great inferno tide, there was only one great pillar of Zhou power left, that of the young crown prince's regent: Duke Wen. It was in this

coming, cataclysmic inferno that Duke Wen became the revered cultural hero and paragon to Confucius himself. It was also in this war, that the supremacy of the Mandate of Heaven was fully confirmed. Heaven's will would be proven again in battle.

Thank you to my Patrons who has contributed $10 and above: You made this happen!

➢ ☯ MK Celahir

➢ ☯ Muramasa

➢ ☯ Thomas Vieira

➢ ☯ Kevin

➢ ☯ Vincent Ho (FerrumFlos1st)

➢ ☯ BurenErdene Altankhuyag

➢ ☯ Stephen D Rynerson

➢ ☯ Michael Lam

➢ ☯ Peter Hellman

➢ ☯ SunB

.jpg)

%20(1).png)

Shang (Red) and Zhou (Blue.) Count Ji Chang's domain resided in the western regions of the Wei River Valley (Blue), there lived his people, the Zhou tribes. There was ongoing debate both among ancient Chinese historians as well as modern historians whether they were truly completely Sinicized (mirroring that of the Shang of the Central Plains) or only partially, that though they were related to the Shang and are part of the larger Yellow River culture they were still only partially like the Shang. In the 3000 years hence this era the Wei River Valley in modern Shaanxi had been largely terraformed to be able to provide sustained agriculture but in ancient times the valley was more divided, and tribes in the area both farmed and for some also lived a semi- pastoral lifestyle.

Shang (Red) and Zhou (Blue.) Count Ji Chang's domain resided in the western regions of the Wei River Valley (Blue), there lived his people, the Zhou tribes. There was ongoing debate both among ancient Chinese historians as well as modern historians whether they were truly completely Sinicized (mirroring that of the Shang of the Central Plains) or only partially, that though they were related to the Shang and are part of the larger Yellow River culture they were still only partially like the Shang. In the 3000 years hence this era the Wei River Valley in modern Shaanxi had been largely terraformed to be able to provide sustained agriculture but in ancient times the valley was more divided, and tribes in the area both farmed and for some also lived a semi- pastoral lifestyle..jpg)

.jpg)

2%20(1).jpg)

W.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

%201.jpg)

.png)

.png)

W.jpg)

1.png)

.jpg)

%20(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

Comments

The Zhou may have been related to these Inner Asian nomads and when they conquered Shang, they introduced this feudal system of allegiance. Just like when Attila the Hun invaded the Roman Empire, they Huns introduced feudalism to the Germanic peoples of Europe who would establish it from Spain to Germany. Both Shang and Graeco-Roman civilization seem oddly 'un-feudal' don't you think? From Shang to Zhou, we see a distinct break in culture and political organization, just like we see in Europe, ... from a system of Republics and democracies and citizen participation to one of monarchy, royalty and feudalism.

We see this again in Chinese history actually with the Mongol Yuan conquest of China. A moving away from Song Meritocracy to Yuan feudalism.

I welcome your thoughts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shimao

As for Shang culture, material culture kind of showed that early Shang was much more domineering and autocratic, at least in its ability to assert its will and introduce similiar wares and walled- fortified towns across a great expanse, as far as the banks of the Yangtze River.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panlongcheng

But later by the last half of the dynasty it became more sedentary and power- at least direct power the Shang king exerted became largely relegated to a permanent capital (Ying) before this time the Shang had a ceremonial founding capital and then often camped where the King was (the earlier greater assertion of its authority across the regions) but later when the dynasty became settled around Ying it began to delegate a lot of its power and missions to local proxies. My own theory is actually that by the late Shang there was already a semi- feudal type of system between overlords and regional wardens, or Late Rome and a region's Magister Militum and Dux. And I think Shang had a version where important ministerial positions overlapped that of a trusted local aristocratic clan. In my opinion the transition to Zhou's feudalism wasn't a snap sudden transition, but was already evolving to be that.

I'd also raise the same for your example of late Rome as well with my earlier examples. Because of truly weak imperial Roman authority and its slew of mostly useless Emperors after after Theodosius (bless you Majorian you were too good for late Rome) in a time that coincided with endless swarms of trespassing barbarians, Rome also delegated and outsourced its defensive needs to local strongmen that swore to them- at least in pretense in vassalage. It's based on needs and not necessarily anything specific to steppe cultures, late Tang did it with various useful ethnic groups too like the Tanguts and Shatuo Turks and threw them against rebels and Khitans etc.

I have friends who are much more into the archeological history of ancient China than I am and they have suggested that a common ancestor group migrated into the Central Plains of China from what was Burma then northward into the Yunnan/ Sichuan mountains and then forked in settlement directions, the progenitors of the Longshan culture~ of the Yellow River basin went east while those that would establish the Tibetans settled west. Though Longshan among ancient Chinese civilizations were already pretty late.

1. Was the Duke of Zhou really that paragon of virtue, or was he a usurper?

2. Was there a philosophical conflict between the Duke of Zhou and the Duke of Shao regarding the Mandate of Heaven, with the Duke of Zhou believing it was by their virtues/effort/skills that the defeated the Shang, or is the Duke of Shao right in saying it was by the Grace of Heaven that the Zhou triumphed?

3. What was the origins of the Zhou 'feudal' system, where's the precedent? The Shang didn't rule like the Zhou with surnames and separate states.

4. What was the situation with the Nomadic peoples and their relationship with the new Zhou Dynasty? did it resemble later dynasties?

Thanks for all your work!

When the Duke of Zhou retaliated against the 3 guards he not only had the full blessing of the young King Cheng of Zhou but King Cheng of Zhou actively participated in campaigns and led forces to put down his 3 uncles and the realm of Shang revanchists. Furthermore King Cheng trusted Duke of Wen's counsel in the rest of Duke Wen's time at the royal court. However I mentioned that this is gray because tradition stemmed from Duke Zhou's time asserted that the young King Cheng was in his minority, however records also stated that King Cheng led armies on campaigns in the east against Di rebels aligned with the dispossessed Shang. The fact that he led armies disproves Wen's assertion that he must be a Regent for a child that's not a child.

2. I know there is a contention between Duke of Zhou and Duke Shao but have not read up deeper onto this subject, but I am interested in looking at their debates if there are sources I can jump onto and read up on.

3. Early Shang had greater control over its territories and it seemed that its territories were larger. They expanded all the way to the Yangtze Basin in cities like Panglong City and also bumped against the Sichuan basin and footed the Bohai Sea. There was a more direct input of their material culture in these sites. Shang excelled at Bronze on a level that is almost monopolistic (they had a peer- competitor in this field with the Sanxingdui but the Shang wares are respected far and wide) their walled capital has a vast district for bronze forging and it was an industrial power house. They also build large walled cities at key points that are architecturally very similar, meaning that likely a core of trusted insider institutions (royal engineers etc) were deployed and rotated across the realm. This showed a strong centralized system with a reliable body at the King's disposal.

At the time Shang power is also more fluid, in that the court moved around wherever the King is- similar to how HRE capitals usually revolved around where the Emperor is currently holding court. From a power's perspective the Shang kings married many princesses and concluded vast alliances with all of those married allied clans, but power often favors the newly favored- in laws and diminishes for those who are further away from the current King's blood. However by the mid- late Shang, after they permanently cited at Yin, it would seemed that the Shang greatly began to rely on a series of vassals. This likely showed that for some reason the Shang Kings were weakened at this point, or that there was already a strong bloc of nobles (tribal clans) that controlled key sector of his court. I lean to the interpretation that some factor or crisis might have weakened the royal dynasty and that on a regional level he had to delegate to strong noble tribes in the region. I rest my assertion on historical patterns of China itself. Zhou did this after the death of King Zhao against Chu in Western Zhou and also King You's death to the Rong that kick started the Spring and Autumn period. Both of those instances kick started more reigional self administration bc the royal court was weakened. Same for Han in the Yellow Turban Rebellion and Tang after An Lushan Rebellion etc etc etc.

4. Zhou embarked on a very aggressive series of expansions on all sides during the early Western Zhou. Largely in an effort to secure internal domestic peace. King Cheng and later King Kang and then King Zhao's reign were all devoted to wars against traditional "barbarians" that long plagued the Shang subjects. It's a compensation effort to ingratiate themselves to this society. In the north and west they warred against the Rong, in the east Cheng and his successors pacified the Di, annexed Yan and Qi in what would later become Shandong (which was a very rebellious backwater) and secured the vassalage of Xu. And in the south, provoked a war against Chu and its confederated allies.

The early Zhou succeeded in 3 of the former, but in the south was utterly crushed by the Chu, -this both allowed Xu to reneg on their vassalage and rebel and also made many of the Zhou nobles assert greater independence from the Zhou court, this sent the Western Zhou into a steady decline.

https://discord.gg/MzCYM3dp