Spring and Autumn Era: Part 3. The Chu Wrecking Ball 春秋: 一飞冲天

...They Went Native...

Music: The South Barbarians

The Lords of Chu were supposed to crush the myriad of southern barbarians, instead, they went native. Instead, they came back as their Kings. In the thorn- choked thickets and torrential rivers of the south, the Kings of Chu proudly bore the last name of Xiong 熊 (lit. "Bear,") and led hundreds of tribes that violently shunned the Zhou ways. This is the story of the Zhou people's eternal Boogeymen- and the headstrong King who led such a "savage" state to- as he described "soar into the sky."

For those who are familiar with the plot of Apocalypse Now, the founding of Chu bore some similarity with that of Colonel Kurtz. Although the Viscounts of Chu were once tasked with taming the endless wild of the thorn- choked thickets of the south, instead, the Viscounts of Chu joined the wild in all of its horror and savagery ~this would be the version if you are a bystander from the Central Plains of China. If you are a dweller of the Central Plains, Chu is the cautionary tale of spiraling descent to madness, where man regress to beasts in the wilds beyond. However- if you choose to tell the story of Chu from the Chu themselves? ~ it becomes glorious. The story of Chu from themselves tells the tale where exiled students bested their master at their own game, and where an endlessly maltreated vassal protested their condition with unrelenting violence and became the greatest power there is.

THE STORY OF THE BOOGEYMAN

Music: Unifying the Tribes

Animals- especially bears held sacred cultural importance to the Chu. The Kings of Chu bore the uncanny last name of Xiong 熊 (lit. "Bear,") because according to legends, one of its most illustrious ancestral chieftains was referred as the "Yellow Bear." How could the land of "barbarians" eventually became the most sophisticated bronze casters, the producer of the most exquisite of silk, and the maker of the most luxurious lacquerwares?

Chu was there at the very beginning, and there at the very end. The ancestors of Chu Kings warred with the Shang Kings before Zhou was established, and the last Chu King's armies dueled with the armies of the First Emperor of China. Chu was one of the few polities in the world to have endured an 800 years of existence~ its span nearly mirroring that of the Zhou dynasty. However- while the power of the once- all encompassing Zhou disintegrated until they faded into nothing, Chu by contrast rose from a tiny backwater fief- scarcely larger than a small town to nearly ruling 1/3 (and at time nearly half) of all of what was considered the Chinese world.

Beastly people, beastly religion: the discrimination Chu suffered from the Zhou people stemmed from several factors: language, customs, values, all radically different from the dwellers of the Central Plains. At the time, the common language of the Zhou- that of the Zhou court aristocrats 雅言 Yayan (lit: "Elegant Speech") was very different from these Southern dwellers: the language of Chu distinctively denoted as 楚言 Chuyan (Chu Speech) was incomprehensible to both the Zhou ears and in diction. Zhou people revered the spirits of their ancestors while the Chu revered animals.

The preferences of those 2 people differed as well, Chu honored the left hand during greetings, while Zhou the right, Zhou reveres the dragon, Chu reveres the phoenix. Zhou society stressed that people conduct themselves according to Li 禮 ~ a (cosmic) order of propriety, where one should learn one's place and act accordingly within the social network and hierarchy, -such good form is the order of things (later crystalized into Confucianism) while the people of Chu had no pretense for this world view. Thus, even beyond the realm of politics, Chu were seen as the eternal outsiders to the Zhou political order.

NEMISIS OF THE SHANG KINGS

Music: Before

Chu first began as a semi-nomadic tribe that lived in the Central Plains. But after unsuccessfully clashing with the Shang Kings the Chu tribesmen were forcefully banished to the south. When Zhou rose in rebellion- the Chu chieftain, who was once a teacher to the patriarch of the Zhou rulers joined the Zhou and toppled the Shang. For having contributed to the founding of the Zhou state- the chieftains of Chu were enfeoffed with a small county in the south, less than 50 li in size (comparable to a small town) where they would clear out nearby thickets and build a temple to the Zhou Kings. This was done, but despite Chu's continual tributes and sacrifice to the Zhou Kings, Chu was repeatedly sidelined the next 3 centuries.

Chu began in poverty, they were fresh colonizers of the south tasked with clearing the area. Their early settlements and fields were cleared from thickets and won over from the southern barbarian tribes. The early Viscounts of Chu were so poor that it was recorded they have to secretly steal a cow from nearby lords in order to make the proper animal sacrifices to the Zhou Kings. Despite this, the Viscounts of Chu were frequently ill treated. Once, a Chu Viscount came to the Zhou capital to pay respects to the King but was denied entrance to feast with the Zhou nobility- instead, he was treated like a servant and left out with another "barbarian" chieftain in the courtyard. The continual sidelining of Chu laid the seeds for the 50 li county to one day soar into that of over 1000 li. These repeated slights of cold shoulders became outright hostility when~ jealous that the Viscounts of Chu was not paying proper tributes, the offended King Zhao of Zhou invaded Chu with the whole realm of lords at his back.

NEMISIS OF THE ZHOU KINGS

Despite being vastly outnumbered and having only 20,000 soldiers, Chu fought back relentlessly with guerilla warfare for 8 years. King Zhao's 3rd campaign- originally meant to unite the realm and totally wipe out Chu ended in disaster when the Zhou forces were defeated and almost entirely wiped out. King Zhao and his remaining troops allegedly were drowned by a flood while retreating across the Han River. From that moment on, Zhou began a slow decline while Chu fell out of the Zhou orbit and became a rouge state- turning to the cultures of their subjects. 2 centuries later, when the tyrannical King You of Zhou (famous for having feigned danger by lighting warning beacon torches across the entire realm) was slain by the Rong barbarians in 771 B.C and the realm of Zhou imploded into a patchwork of hundreds of states, the Viscounts of Chu smelled their chance, they declared themselves "Kings" while the rest of the realm burned and embarked on a warpath of expansion in all directions. The death spiral of Zhou power marked the beginning of Chu's rise to greatness.

RAPID EXPANSION- RUTHLESS STRENGTH

Implosion of Zhou power in 771 B.C and the 1st days of chaos in the Spring and Autumn period. The first self- declared King of Chu was King Wu- who defeated rivals in all directions around Chu and doubled the size of his realm several times. Within his lifetime, the once still negligible state of Chu rapidly became a monstrous blob in the south, annexing and devouring all states in its path. For the next century, his children would continue the path of rapid and relentless expansion across the south.

THE NEMISIS OF 2 HEGEMONS

King Cheng- King Wu's grandson, - whose reign was parallel to that of Duke Huan of Qi's rise and Duke Wen of Jin's ascension, was the nemesis to BOTH the 1st 2 Hegemons of Spring and Autumn. During Cheng's reign, he vigorously expanded eastward, vanquishing the Zhou- cultured states of Qian, Luo, Ben, Jiao, Sheng, and Xi (some of them so ancient that they were founded during the start of the Zhou dynasty) - He then repeatedly invaded the Central Plains state of Zheng and Cai, until the Chu army reached the south banks of the Yellow River- threatening to spill into the Central Plains. The Central states were so alarmed by Chu that they rallied around Duke Huan of Qi and made him- the 1st Hegemon of the Spring and Autumns era. Empowering him to crush the Chu under the pretext of defending Zheng. In 656 B.C led a massive 8 state coalition to invade Chu. Awed- Chu sued for peace and bit its time, though later, as Duke Huan aged, King Zheng's ambition again stirred. After Duke Huan's death, and Qi imploded in civil war among its princes. Cheng again unleashed Chu to the dozens of states to his east until Chu vanquished them & doubled in size.

It was during this period of continual expansion that a weary stranger came to his court to seek shelter. It was an exiled prince of Jin with his loyal band of followers. Chu hosted them, then, the prince of Jin returned to his state, whereby he became Duke Wen of Jin. When King Cheng's ambition turned northward, Chong'er, the newly enthroned Duke Wen of Jin- came as a protector to the Central states. As a result, Jin and Chu fought a titanic battle at Chengpu, one of the biggest battles of the Spring and Autumn period, whereby Jin resoundingly defeated the Chu army. Duke Wen- after having contained Chu's expansion, became the 2nd Hegemon of the era. While King Cheng, who in his life time had tripled the size of state, was forced to commit suicide by his son. It was in this backdrop that the greatest Chu King was born.

Spring and Autumn world after the shattering Battle of Chengpu. The resounding Jin- led victory would cause a bitter rivalry between Chu and Jin for the next 3 centuries. At this time, great states had crystalized mostly on the frontiers of the Zhou realm. The most important powers extends like a 4 leafed clover radiating from the royal Zhou capital of Luoyang (orange.) At this time Qin holds absolute dominion in the west and guards the realm from the western barbarians. Jin- the hegemon overlord of the realm (blue) guards the north, while Chu, the eternal boogeyman (green) licks its wound in the south. To the east, the collection of Central states (yellow) served as a flashpoint between Chu and Jin.

THE MAD ROYAL CLAN OF CHU- LEADERSHIP PARALYSIS

With the assassination of King Cheng, Chu was sent into remission. However, though Chengpu checked the momentary ambition of Chu, the battle by no means crippled Chu. In the 12 years since King Cheng's death, Chu licked its wounds while tacitly remain involved in the politics of the Central States via proxies. In this silent Cold War they diplomatically jostled for control against the ascendant Jin. During this time Chu did not dare to overtly challenge Jin's supremacy. In the spring of 618 BC, Chu invaded the state of Zheng, however, Jin- under the command of its capable minister Zhao Dun organized a coalition to relieve Zheng and the humiliated Chu backed off.

Despite nearly 2 decades of Jin supremacy, the Central Plain's fear remained. The fear that one day, another ambitious Chu King- in the stripe of conquerors like King Wu and King Cheng would be spawned to lead- at the head of his dreadful people. A King like that would be like breathing the soul back into the comatosed body of an all- consuming war beast.

THE WASTREL KING

Surprisingly, if there were any serious anticipation regarding the character of this newly enthroned Chu King. It must be said that many who had held their breath in fear were dealt with a rather unremarkable sovereign. Xiong Lü 熊旅- the new King of Chu was an idle youth who completely shunned the office of kingship. He did not pass any edicts nor draft any policies. For 3 years, the teenager did not attend court sessions, instead, he spent all day and night on frivol pursuits such as hunting and carousing with harem women.

A NEST OF VIPERS- THE CHU ROYAL INFIGHTING

Xiong Lü's worry- less peaceful upbringing and his spoiled youth was actually an anomaly among the Chu Kings. For although Chu over the centuries was able to boast talented monarchs, many of the monarchs rose to their position through murder and intrigue. Both King Wu and Cheng killed their siblings for the mantle of leadership, while Cheng and many other Chu Kings both before and after him fell because they were assassinated by their children. As such, the Chu royal clan had the infamous reputation of being a nest of kinslayers and usurpers.

THREE YEARS OF SOLITUDE “自静三年”

According to the "Records of the Grand Historian," the teenage King's early reign weas unremarkable. Because the debauched youth completely avoided politics and shunned his office, many ministers within the Chu court were highly troubled. Not only did tongues wag but the young King also left an explicit command that whoever dare to admonish his lifestyle would be put to death without pardon. By this time, not only was Chu externally checked by Jin's hegemony, but internally vassal tribes within Chu were chafing under the wastrel King as well.

For 3 years, the teenager did not hold court, instead, he spent all day and night on frivol pursuits of hunting and carousing with harem women.

Music: Call of the Wild

THE PARABLE OF THE FLIGHTLESS BIRD

It was said that one day, while the King was in the midst of a drunken tyst with his concubines, a Chu minister named Wu Ju 伍举, requested audience with the King to tell him a story. During the session, Wu cryptically told a strange parable, saying: "There is a wonderous bird in the highlands of Chu. However, despite its wonderous nature, it lived for three years but does not fly or sing. I don't know why the bird would act in such a manner?"

The King, who was not oblivious to the references, simply smiled and remarked: "when the Wondrous Bird feels it's ready, it will astonish the world and pierce the sky with one cry 一鸣惊人. But, despite this flourish of wit, in the months that followed, the young King still continued his hedonistic pursuits. This time, another Chu minister named Su Cong 苏从 again came to him, and inquired to the King's nature. This time, the minister's words truly took root, and King Zhuang was moved into duty. From this moment on, one of the most remarkable careers of the Spring and Autumn period began. Zhuang began to attend court almost daily, and for his first acts, he appointed both the loyal Wu Ju and Su Cong to become key ministers of the Chu state.

ASTONISH THE WORLD WITH ONE CRY 一鸣惊人

Since Zhuang's polite confrontation about the parable of the flightless bird, he became a consummate statesman, displaying a new decisive streak that was entirely unseen in his past. The immediate years following this radical shift would be characterized by decisive reform and bold- almost headstrong posturing from the rejuvenated Chu state.

Music: Amon

In 611 B.C- in the 4th year of King Zhuang's rule when he was 20, a massive drought hit across Chu and was followed by a catastrophic kingdom- wide famine. Many sectors of the Chu's local government- unable to locally contain the crisis shriveled in its grasp. During this time, in western Chu, a vassal tribe- at the instigation of the western kingdom of Yong 庸 (an enclave within Chu,) exploded in rebellion. After attacking and killing the Chu local magistrates, the rebel- Yong alliance advanced with lightning speed and raced towards the Chu heartlands. Seeing the snowball effect of the swift rebel army, many Chu ministers tried to advise King Zhuang to relocate and capital and flee. But the King Zhuang of 611 B.C was not the same sovereign from merely 1 year ago in his early reign. Instead, he chose to stay in his capital and root his court like a rock.

Instead, knowing that he both did not have enough troops to split up and man all of the key cities in western Chu, nor does he have enough troops between himself and the rebel army to soak up the rebel attack, -Zhuang opted to do the utmost in delaying his enemies. He sent out messengers and ordered that the Chu commanders currently engaged in battle with the rebels at the front to conduct a fighting retreat. They would fight, then pull out in an orderly fashion, then, entrench again at every key pass, chokepoint, and fortified settlement between the rebel army and the royal capital so as to not let the enemy fan out and take other Chu cities. With these hinge points marked, King Zhuang then began a diplomatic blitzkrieg.

As his western army blooded itself in those series of stubborn last stands, Zhuang sent out messengers that swiftly bypassed the rebel front. These envoys raced to the twin courts of the strong kingdoms of Qin (in what is modern Shaanxi) and Ba (in the Sichuan Basin) - both situated on the flank of Yong, and informed them that the outstretched Yong army is busy bogged down in Chu and unable to protect their own kingdom, that the under manned Yong capital lay wide open and ripe for the taking. Shortly after, Qin and Ba invaded Yong from behind with 2 massive armies. Yong was overwhelmed by this coordinated flanking attack- Chu, taking advantage of the Yong/ rebel paralysis then went on the offensive and utterly crushed the rebel army. Chu then completely wiped Yong 庸 off the map and annexed it under Chu fold. He had acted like a true king of Chu.

This incident marked the first clear demonstration of competent and decisive leadership from the young King of Chu, but Zhuang was not satisfied with simply asserting the old strength of his kingdom. What the punch- drunk young king did next would shock the entire realm in his brazenness.

A ROUGH WOOING- A BRAZEN DISPLAY

In the eighth year of the King Zhuang's rule (606 B.C,) one of the northern vassals in Chu's north rebelled. King Zhuang took advantage of this opportunity and personally lead a punitive expedition at the head of a massive Chu army. The vassal was swiftly crushed, however, despite framing the entire Chu expedition under the pretext of punishing a rebellious vassal, King Zhuang did not stop his advance, instead, his massive army continued northward until it showed up right under the southern walls of the Zhou royal capital of Luoyang.

Music: Blood and Glory

Then- within the sight of the walled southern suburbs of Luoyang, King Zhuang did the unthinkable and held a massive "military parade" with his army. They beat their massive drums of war, his chariots raced and flew their war banners, and the hundreds of Chu formations conducted military exorcises right within visual distance to the stunned royal capital. After this brazen display, King Zhuang would return to his camp, but the exorcises continued daily.

The impudence of this move could not be understated, at the time, although the Zhou Kings were merely powerless figureheads and only were allowed to control lands surrounding the capital of Luoyang- Luoyang and the Zhou court were still seen as off- limits to...everyone. Dreadfully alarmed, the Zhou court soon sent out delegates to the Chu camp so as to inquire the reasons behind such a provocative flex.

INQUIRING THE WEIGHT OF THE DING IN THE CENTRAL PLAINS

The unsettled Zhou King, dispatched a trusted loyal minister Wang Sunman to the Chu camp, so as to inquire as to the intention of the Chu King. King Zhuang received Sunman warmly and hosted him on the bank of the Luo River. However Zhuang responded by raising the question as to the "weight of the great 9 legged Ding (a tri-podded bronze vessel) of the Zhou kings. It was a question that bellied unimaginable naked ambitions.

For context, the ancient Ding- of the royal house of Zhou is an ancient standing treasure that served as an emblem of the Zhou Kings, the veiled question in regards to its weight was not only a question to the object but a question as to the symbolic foundation of the ancient Zhou state. The clever Wang saw through this line of questioning (the Zhou Kings and the rest of the Zhou realm's nobles never acknowledged the insolent Chu rulers as Kings, and stubbornly still referred to them as merely "Viscounts.") simply responded that the Ding's weight is too much and beyond fathom.

To which Zhuang countered in a veiled retort that if all of the arrayed Chu soldiers simply unscrewed the Dagger ax blade 戈 off from their halberd handles, the bronze from their collective bronze could match- several times to the weight of the Zhou King's Ding. The unmoved Wang Sunman then rebuffed Zhuang in one of the most quoted adages in Spring and Autumn history. "The authority to reign over the realm lies in righteousness and not the Ding."

The answer seemed to have impressed King Zhuang and made a great impression~ especially in relation to Soft Power and legitimacy. It is plain to all that Chu is strong and Zhou- if Chu wished, Zhou could be easily toppled. However, true power, at least in the eyes of the realm's subjects in no way merely lies within physical objects and physical cities. Ultimate power lies in the belief and world view in regards to norms and institutions such as the Kingship of Zhou and the relationship between the Zhou King, the nobles, and the rest of the realm. Simply put: Zhou endures because of the traditional niche in which it still occupies. Even if Chu sacked Zhou, they won't be seen as rightful Kings without a fuss from every other state. Having internalized this lesson, the Chu King departed with his army and devoted his next years to reforming his state.

MONUMENTAL WATERWORKS

Music: Circle of Life (and Death)

King Zhuang then embarked on an aggressive infrastructure project of dikes, reservoirs, and irrigation networks. Having long realized the vulnerability of his state to droughts- and well remembered the rebellious blowback from droughts and famines, Zhuang hosted many able engineers from his kingdom with the goals of securing food production and food independence.

MASSIVE WATERWORKS- AGRICULTURAL IRRIGATION

Swift appointment of talented ministers was a hallmark of King Zhuang's reign. Polymaths like Sun Shuao- were elevated to the position of Chancellor within the Chu state- a peerless builder, Sun Shuao was entrusted with overseeing many endeavors of the state. Sun would diver water to the Chu interior. There would be a three stage developmental model for the Chu state, beginning with the mastery of water > securing fresh farmlands and food production > strengthening of the state in manpower and commerce.

In the areas of Northern Hubei and southern Henan, Chancellor Sun Shuao built a series of monumental artificial lakes that served as Chu reservoirs and fisheries. The erection of these dams allowed the strategic flooding of flat valleys in modern-day northern Anhui province, the reservoir which was created spanned a circumference of 62 miles (100 km) Sunshu's designs were both avant- garde for his time and elegant in its simplicity, sometimes, dam walls were made into tiered steps and excessive water could be channeled down hill via these steps into other ponds.

Having irrigated some 6 new million acres of newly converted arable lands, the Chu population dramatically rose during King Zhuang's reign.

Since Sun's time, this ancient reservoir accumulated tons of north-flowing water that came from the mountains north of the Yangtze River, and supplied an irrigated area of some six million acres (24000 km²). These reservoirs and irrigation networks were so effective they were maintained continuously for the rest of the Zhou dynasty, and even later imperial dynasties such the Han, Sui, and Tang. In ancient times, the Chinese had called this reservoir the Peony Dam. Today, the large reservoir created 2 and a half millenniums ago by Sun still exists, known in modern times as the Anfeng Tang (Anfeng Reservoir). The population and economical boom resulted from this irrigation effort strengthened Chu's manpower and coffers.

RESPECT- CULTIVATING PRESTIGE

Music: Hardboiled...Afraid

By the middle of King Zhuang's reign, King Zhuang's irrigation efforts came to fruition- Chu's population boomed and its economy flourished. With the Chu house in order, Zhuang again contemplated Chu's place among the other Zhou states. After the posturing at the Luo river many year back, Zhuang was keenly aware that raw power alone was not sufficient in upholding his world order. Thus, to truly cement Chu's position of leadership, it needs soft power as well. In order to bolster Chu inter-state prestige, Zhuang employed talented advisers and polymath from around the Zhou realm. Zhuang also enforced its royal laws on many member of his royal family.

An incident that occurred during this period involved King Zhuang's own Crown Prince. The law stipulated that any chariot or wagons that entered an estate (or crossed its moat) without stopping should be punished. This was especially so for royal residences like the King's palace. However, one day, the Chu Crown Prince- in haste to report to the court, allowed his carriage to race into the royal enclosure without stopping at all. Despite the palace attendant's pleas he did not stop and his carriage rode past the moats, believing himself to be above the law.

Therefore, the judge guards at the royal palace gates immediately ordered the carriage stopped and destroyed, and- proscribing the strictest punishment of the law, had the Crown Prince's carriage driver executed. The Crown Prince was outraged by this and raced to his father seeking punishment for the judges. However King Zhuang rebuked son, firmly stating that edicts and laws are created to ensure the stability of nation. The judges who followed the law without bais did so because these laws were layed down for the good of the nation, and them procecuting it to the letter of the law was within their full rights. The King's judgement in this case soon spread throughout the Zhou realms and won him many praises.

INTEGRATION INTO THE ZHOU POLITICAL ORDER

There is a clever subtext within Zhuang's judgment as well. Since he had long spotted the chasm of differences between Chu and the rest of the Zhou- cultured world order. Admonishing his son in order to respect the general norm of the (realm's law)~ also signaled that he himself was different from the rest of the "wild" Chu Kings before him. And implied to the external observers that Chu would play by the rules of the Zhou political order.

INTERSTATE MEDIATION- MANUVERING

To secure Chu a platform in the realm's politics- and to insert Chu into the realm's political discourse. King Zhuang ordered that Chu nobles rigorously study Zhou culture and Zhou classic texts- familiarizing themselves with Zhou norms. This aggressive integration (at least among the Chu elites) allowed the Chu lords to place themselves- at least culturally on equal grounds with the nobles of the rest of the Zhou states. After this period, in diplomatic banquet and ceremonies, Chu nobles and scholars were able to converse with the rest of the Zhou nobles fluently in ancient classics and cite precedents as if they were raised from the same school and culture. With these new cultural foundations, Chu was slowly seen as part of the "insider's club" and gradually trusted with more say in the realm's affairs among its other lordly peers.

THE ALIGNING OF STARS- OPPURTUNITY OF A LIFE TIME

On these merits alone, King Zhuang's domestic achievements would already have been mighty and peerless among his contemporaries. However, fate would align on his behalf that would catapult him to be peerless among even the greatest sagely rulers of the Spring and Autumn era. On the 13th year of King Zhuang's rule, several events all converged together which created a massive opening for Chu to soar into the heavens. Here is when Zhuang also became one of the most powerful military men of his era as well.

Bridge Gate: situated right beside the Zhou capital at Luoyang, Zheng (Yellow) was seen as a land bridge during the Spring and Autumn period. Both Chu and Jin saw Zheng as a useful buffer against the other. Because Zheng straddled the both sides of the Yellow River, whoever had Zheng as a vassal was able to rapidly have their own massive army show up at their enemy's boarders.

In 601 BC, the supremely influential Jin minister Zhao Dun died- for decades he had been the true power behind the Jin throne and was once responsible for scaring off King Zhuang's own father King Mu from a failed northern invasion of Zheng in 618 BC. Just a year later, Duke Cheng of Jin died as well- quickly followed by Zhao Dun's successor Xi Que in 598 BC. Spontaneously- as if through divine providence, Jin- the old nemesis of Chu was internally in disarray. Chu's time had come. Sensing his time, King Zhuang immediately organized his army and marched on the neighboring state of Zheng to his north in 597 BC.

Zheng had once been a minion of Chu and a representative of Chu's interests in the Central Plains. However, after the battle of Chengpu- Zheng, plus nearly all of the Central states were made into vassals of the Jin. For King Zhuang, Zheng under Jin's sway was a dagger that pointed squarely at Chu. Since Zheng gave Jin military access and since Zheng straddled the crossing of the 2 banks of the Yellow River, having Zheng as a Jin ally meant that at any time- should Jin wishes, they could instantly ford cross the Yellow River without resistance and pop right up at Chu's boarders. However, if the state could be subdued and forcefully overawed by Chu- then Chu could instead turn Zheng into an obstacle that not only denied Jin a crossing but also a base of forward projection.

LEADERSHIP- POLICE ACTIONS

Personally leading his massive army, in 597 BC King Zhuang surrounded and besieged the Zheng capital for 3 months. After seeing the futility of holding out, Zheng resistance faltered and the capital sued for peace- Zheng was humiliated and its exasperated Duke Xiang marched bare chest before the Chu King and prostrated himself in submission. For anyone familiar with Chu's ancient history, it looked like a moment right before the Chu King would completely annex such a state. However, King Zhuang did not do so, and instead, he raised Duke of Zheng up as a Chu ally.

What then politically unraveled between the state of Chu and the nearby state of Chen inadvertently exploded around one of the most infamous femme fatales of the Spring and Autumn Period. Lady Xia Ji 夏姬 was one of the most beautiful and rapturous women in all of Chinese history. She was known to have been intimate with at least 10 lovers and married half a dozen times, whereby 2 of her husbands and her own son were killed as a result of her affairs.

Originally a noble lady from Zheng, Lady Xia's first marriage was to a respected elder minister in the nearby state of Chen. However, while she was there, she must have caught the eye of the Duke of Chen. Her husband soon died of old age, and a court master of rites soon married the widowed Xia. However- what happened next sent the tongues wag. Lady Xia then gave birth to a son, but the son was born much earlier than the 9 months from when the new husband had married her, and it was unlikely she was impregnated by her deceased husband. The boy that was born form her- named Xia Zhengshu, would grow into adulthood achingly aware of his uncertain parentage.

A JOKE THAT NEARLY TOPPLED A STATE

Lady Xia's 2nd husband eventually died and she was reported to had an affair with Duke Ling of Chen. It was reported that once in court, the Duke boasted that he was having passionate relations with Lady Xia- and to prove this, he took out an underwear called ri fu that was hers and brandished it to his guests (which he proclaimed was given to him by her as a badge of her affection.) However- the Duke's brag promptly elicited an unexpected round of chuckle from his 2 main secretaries. For it turned out, they each also produced an underwear that was hers and confessed they also had relationships with her as well. The 3 then broke out in laughter and soon it became public knowledge that the widow lady Xia was intimate with a rather large gallery of people. The illicit and simmering tension eventually bubbled to surface when Lady Xia's son was taunted by his mother's lovers.

The small state of Chen in 598 BC. Chen was situated right beside Zheng- after the police action against Zheng, Chen's internal affairs would grab Chu's (rather befuddled) attention.

Once, during a night banquet, Duke Ling joked to Xia Zhengshu that he looked nothing like the late master of rites that was supposed to be his "father" - then pointed to the 2 secretaries who were Zhengshu's mother's lovers and joked that "You look more like you could be Zhenshu's father," but the secretaries joked back and remarked that "No sire, he also look like your Lordship." (the cutting remark might have an extremely solid foundation since it was very likely that the Duke had long been intimate with Lady Xia, but married her off to the wizened ducal master of rites to keep up appearances) the joke struck home and Zhengshu was roused to a black rage. After the banquet when Duke Ling was departing the mansion, Zhengshu grabbed a bow and shot the Duke to death at the gates. This crime of passion- as (mis)fortune would have it, occurred right during King Zhuang's northern campaign into the Central Plains.

Xia Zhengshu's unexpected coup shocked both Chen and the nearby powers. Immediately after the assassination, Duke Lin's son fled Chen and showed up before King Zhuang bare-chested and pleading for help. Meanwhile, the inexperienced Zhengshu tried to seize the government by declaring himself the Regent in charge of Chen. His punishment was swift, and in only few months, Chu forces arrived at Chen and took the Chen capital, killing Zhengshu and taking Lady Xia captive.

For Chen- this could have not came at a worse time. Chen was utterly defenseless and Chu had total power to completely annex the state. All the chips were in Chu's hand. Instead- like with Zheng. King Zhuang did what none expected and politely installed the already deposed son of Duke Ling as the new ruler of Chen~ as the new Duke Cheng of Chen, turning Chen into a Chu ally. Chu's clemency shocked the rest of the realm- again, like with Zheng, Chu had showed remarkable restraint. Not only this, but they showed great justice and magnanimity in intervening to selflessly restore an usurped ruler. For this, Chu again was widely praised by many in the realms as a mediator. However, Chu's clemency was unheeded by one power- the single power that would not take Chu's side in any matter, Jin.

Furious that Chu had turned Zheng into its vassal, in 597 BC Jin mobilized a massive army and marched south to punish Chu. The wrath of Jin- the Hegemon's army was on its way.

Music: Wheels

THE HEIGHT OF CHARIOT WARFARE

Art by 咪咪妈的刘sir

A PLATFORM OF CHAMPIONS

The chariot was introduced to China as early as the Shang dynasty. The 7th century- 3th century BC marked the height of chariot warfare among the great states of the Spring and Autumn era. Once, the Zhou Kings of Western Zhou was able to field thousands of chariots of a united realm in their military expeditions, however, with the slaying of King You by the Rong barbarians in 771 BC, Zhou authority drastically declined. By the Spring and Autumn era, great lords were each able to fields several hundreds of chariots of their own.

Quadrigas chariots were deployed during this period- yoked by 4 horses. By the mid and later Spring and Autumn period practically all of the charioteers were heavily armored. Some lancers wielded jis with several dangerous blades. Nearly all chariots were either 2 horsed or 4 horsed. States such as Jin boardered the steppes where they warred constantly with chariot- borne enemy invaders.

The most militarily prominent state of the early Spring and Autumn period was Jin 晋. In 661, Duke Xian of Jin 晋献公 (r. 677-651) doubled his armed forces to build the upper and lower division (shangjun 上军, xiajun 下军). Duke Wen 晋文公 (r. 637-628), who took over the role of the 2nd Hegemon of this period further expanded his army and further divided the army into 3 divisions, Upper, Middle, and Lower, and each branch with its own subdivision of Upper and Lower. This allowed for greater tactical autonomy. The tactical fluidity of Duke Wen's army and its localized sub- commanders allowed the Jin army to pull off highly complex maneuvers that decisively crushed the Chu army at the battle of Chengpu- pinning and then ripping apart both of the Chu left and right armies before the center retreated in disgrace.

EVOLUTION OF CHARIOTS- CHARIOT ARMOR

Above: Threat range of a chariot. In this graph 2 opposing chariots rushes to engage each other (the lancers are located on the right side of the craft) however- it also demonstrates the blocking potential of the chariots as the chariots also blocks the movement of the vehicle directly in front of them. Center: Late Spring and Autumn era chariots, by this time both the horses and the riders were almost always heavily armored, with thick lacquered hide armors protecting the horse's front and sides heavy armor protecting the riders. Material evidence excavated from the Tomb of the Marquise Yi of Zeng (Sui).

CRAFTS OF WAR

Charioteer's heavy armor- black lacquered hide stitched together with red silk. Hide armor during this period varied from ox hide and more expensive hides such as rhino that are almost definitely reserved for the aristocrats. The boots of some aristocrats are fashioned from white deer skin.

The troops riding the chariot (chebing 车兵, lit. "chariot troops") were protected by corselets and therefore called "armored soldiers" (jiashi 甲士). Their mode of fighting required extensive training, not only to achieve mastery in hitting the enemy, but also to thrust into the heart of his formation and kill enemies and capture their officers. As chariots became heavier, chariots were manned by three men, the left one fighting with bow and arrow, the right one with spear and halberd, and the central person steering the vehicle. The warhorses were sometimes armored with prized lacquered hide armor. Lacquered hide armors from this period sometimes included those made from rhino hides, which were nearly impervious to slash and piercing blows.

FOOT GUARDS

Each chariot was usually accompanied by a certain number of infantrymen (tubing 徒兵, or "ground troops" lujun 陆军) , it would be their job to exploit any breakthroughs the chariots made. However the number of infantry guards were not fixed. They ranged between 10 and 100. Ten footmen was the usual number of troops accompanying a chariot during the early Spring and Autumn period, and 75 was a common size in the late Warring States period for light chariots. The army of Chu used 100 persons per chariot, but this was not necessarily adopted by other states. The Terracotta Army soldiers of the Qin army had varying numbers of foot guards for their chariots.

This bronze blade was once attached to the axle of a chariot wheel, and is known as a wei. It was used to keep enemy foot soldiers away from the chariot.

Music: Sound of Heartstrings

597 BC- THE SHOWDOWN AT BI

The Jin dilemma. When the Jin army arrived- it was placed in a difficult position. Although the Duchy had dispatched its massive relief army under the pretext of "rescuing Zheng" (whose capital at the time was still besieged by the Chu army) by the time the Jin army arrived Zheng had already surrendered and signed an alliance to become Chu's vassal. The loss of this cassus belli, along with their precarious position of being overextended beyond their own domains placed the Jin expedition in a dilemma: well aware that the state's veteran senior leadership had only recently died they were not enthusiastic about the prospect of a climactic showdown.

But neither could they simply pull up the tent pegs and pull out either, for having lost a vassal to naked Chu aggression would fundamentally undermine Jin's position as the Hegemonic policeman of the realm. This created a rift among the Jin commanders, about whether or not to meet the Chu forces in battle. The Yellow River thus marked a Rubicon of sorts. Xun Linfu, the new commander of the Jin army (relative of the only recently deceased chancellor) waited and camped along the northern bank of the Yellow River.

MUTUAL INTIMIDATION

Ironically, the Jin timidity was also somewhat shared by the Chu leadership as well. Although it was not recorded the exact number of troops gathered at Bi- it is very likely that the numbers gathered was above 1 hundred thousand or a few hundreds thousands. King Zhuang saw the massive number of Jin camps that was across the river and too confessed that he was rather apprehensive of commuting to a duel with such a well disciplined- and veteran army. His senior advisers Ling Yin and Sun Shuao too were not sure of victory, and advocated withdrawing the Chu army. Despite this, King Zhuang did the unexpected and pulled his army 30 li back from the Yellow River's south banks and sent messengers to the Jin army offering battle.

The Battle of Bi had many mirrored- similarities with that of Chengpu- both began between the Chu and Jin under the pretext of aiding allies- both followed with a formal and polite pull out giving way for the enemy to cross the Yellow River offering battle. To let the Jin cross, the Chu army decamped and pulled back 30 li.

What ultimately persuaded King Zhuang was the advice from Wu Shen 伍参, Zhuang's most influential commander who pointed out that despite appearances, the Jin army's leadership was paralyzed. With the recent death of its duke and its 2 senior ministers, the current Jin army was led by an unproven commander- in- chief who had yet centralized authority thus had to deal with sub commanders who are unused to his leadership. Wu inferred that in the heat of battle the sinews of Jin leadership would fray and lead to problems among the various overlapping branches of Jin sub commanders- likely causing them to offer competing orders. Having strongly made his case of the Jin army's disadvantage- Wu urged his liege to take full advantage and lure the Jin to overcommit itself into a battle it will be too uncoordinated to win.

BATTLE OF BI- EARLY SKIRMISHES

The Jin commanders where however no fools. Although they advanced into what the Chu intended to be their trap. They did not knowingly presented any weakness to their enemy. In order to make their position unassailable the Jin army arrayed itself all along the bank of the Yellow River with the mighty river covering their whole flank. To further bolster their impeccably chose site of defense they also anchored their main army between 2 small tributaries of the Yellow River. Thus- surrounded on 3 sides by easily defensible river banks, they faced the south- the only direction where the Chu army would attack from. Even at their front, there laid another river between them and Chu- which would act as a mighty moat if the Chu should dare to attack.

BI- RAIDS AND REPRISALS

Luring the Jin to simply sit here will also serve another purpose. At least for Chu that is, since every day the Jin army is staked in this position, they are staying far away from their homelands. Meaning Jin's neighbors, especially the powerful and ambitious Qin may become...hungry looking toward Jin's undefended homeland. Watchfulness described the mood of both armies. Chu feigned diplomatic parlay several times- and used these opportunities to confirm that there was great dissention and disagreements among the Jin generals.

Violence at Bi broke out in sweeping chariotry raids. Since both armies were deployed in well defended areas, the Jin cavalry attempted to bait Chu from its position several times by ordering its nimble chariotry divisions to raid and fish out Chu pursuers.

THE KING RODE OUT IN PURSUIT

Like Chengpu- the battle of Bi also had a climactic episode where a dust storm blanketed the battlefield obscuring the views of the Chu commanders.

At night, Jin dispatched 2 veteran chariotry commanders- Zhao Yang and Wei Qi with detachments of charioteers to assault the Chu Camps, even riding deep within the camp and killing Chu soldiers. When morning came, these vexing raiders were chased away by none other than King Zhuang himself- who led from his chariot in a headlong pursuit along with dozens of chariots and guards- Several bouts of swift chariot battles wheeled between Jin champions and the Chu pursuers- with King Zhuang ending in victory every time. Slowly- with distance, he and his guards disappeared from the view of his chancellors and generals.

THE CHU WRECKING BALL

Music: Chi Blockers

During this time the Jin commander Xun Linfu sent a force to escort the two generals safely back to Jin lines. However, right at this moment, the Chu general Pan Xie- who was ordered to chase down Wei Qi's chariots saw a massive yellow storm of loess dust that was seen in the distance- a massive storm that just might have been made by a great army as big as the Jin.

Panicked, and with their King still lost from their sights, an agitated Pan Xie raced back to the Chu camp and reported that the "Jin army was here!" bearing down on the Chu position, worse yet- that King Zhuang was no where to be seen.

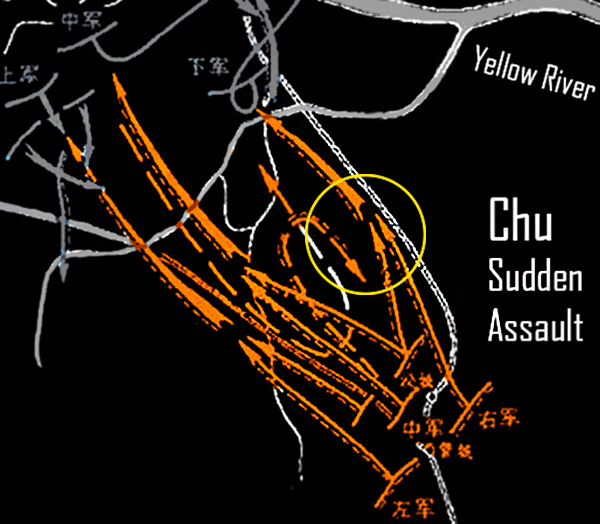

Hearing this, the Chu Chancellor Sun Shuao immediately ordered an all out assault of all Chu forces against the Jin position:~ screaming that "I would rather attack my foes than let them attack me!" 宁我薄人,无人薄我! As if posseted by desperate madness, the Chu army surged forward. chariots galloped, sergeants galloped, and barreled towards the Jin army. They would come as a wrecking ball.

During the attack, the forty chariots led by Chu General Pan Xie to pursue Wei Qi Chu army's rejoined Chu's right-wing formations. The speed of Chu caught the Jin army completely flat- footed. For in the Chu army's desperation, they had raced to the river bank which was intended by the Jin to use as a defensive moat. What followed was a desperate Jin scramble to retain the "moat"

Ironically, the people least prepared for an all out battle turned out to be the Jin army. The dust storm that Pan Xie and Sun Shuao saw in reality had merely been a natural occurring phenomenon, and when the Chu army- in full force suddenly appeared all over the horizon in front of the outstretched Jin deployment, the Jin commander were all caught flatfooted. With the shoe actually on the other foot, it was the Chu which raced out of the dust storm like a demon possessed.

Realizing the gravity of the situation- and that the Jin line was woefully too far apart to absorb this concentrated wrecking ball, the Jin commander opted to surge forward and try to dissipate the Chu rolling momentum. Seeing the Chu racing to cross the river which acted as the "moat" between the 2 armies, the flustered Xun Ling's father at the Jin army's center quickly ordered his front rush forward and bottleneck the Chu advance at the moat's bank. The Jin center beat their drums and commanded as many Jin soldiers to plug up the crossing as possible. However, even though many brave Jin soldiers rushed forward, they were no match against such a relentless and concentrated assault. Thousands of Jin soldiers were cut down and hacked to pieces, and just as they desperately struggled, Chu's right wing made contact with the Jin Lower army in the east section of the river.

Fighting here was also desperate and savage, but they still failed to prevent a Chu crossing, they were overwhelmed by the Chu soldiers at the crossing and many Jin officers were captured. This is not to say that the Jin army- although having been completely surprised, did not offer resistance. In some areas, the Jin mounted fanatical counter attacks. In the same eastern front, the Jin regrouped and under Wei Qi the chariotry charged deep into the Chu lines and pushed them back, during this suicidally brave counter attack, Jin general Xun Shou shot and killed the elderly Chu royal master of rites 连尹襄 upon his war chariot and captured the younger brother of King Zhuang.

JIN COLLAPSE

But despite these tactical heroics, on a strategic level the Jin army was collapsing in the center and in the east. Both the Center army and the Jin Lower army retreated and desperately raced off the field. The Center and Lower army raced east while the Upper army wobbled westward. In the east it soon turned into a desperate rout with tens of thousands of soldiers pushing and shoving each other down for boats and ships long the Yellow River's bank. With the Chu army hot on their heels thousands of Jin soldiers jumped in the river and drowned. By now fully in command of his army again, King Zhuang ordered his general Pan Dang to lead a crack division of swift charioteers to rout the Jin upper army to the west of the battle field. Despite bloody losses, the Jin Upper army in the west was the only branch to pull out in good order. By the evening, the remnants of the Jin army were all defeated from the field.

Chengpu was avenged several folds. Not only was the Jin army beaten, it was resoundingly crushed for all to see.

A MATURE INSIGHT

Music: Ritual of Peace

When the next dawn came, King Zhuang awoke as the most powerful man in all of the Zhou realm. He took his soldiers beside the Yellow River banks- and told them to drink up (for this- the Central Plains was their ancestral home several centuries ago.) He too drank from its waters and looked north, then he led his own warhorse to the Yellows River and had them drink from the Yellow River as well.

Delighted by this victory, Zhuang's advisors recommended that to commemorate this remarkable battle and cement Chu's supremacy over Jin, he erect a 京观 Jingguan- which in the Spring and Autumn period was a grim monument of victory. A Jingguan was a pyramid of skulls- made from the severed heads of defeated enemies, and mortared together so that the bones and the earthwork eventually marks the site of battle and commemorate the battle for the victors. The casualties from Bi alone was equal to several pyramids worth of heads.

King Zhuang refused. Instead remarking on the poor logic of such a position, remarking that these are all good soldiers who had came because their Duke demanded them to play their part, and they had dutifully served and died for it. Instead King Zhuang ordered that the fallen Jin soldiers and generals be properly buried and that an ancestral temple to be built along the Yellow River's shores so that spiritual sacrificial rites to the river god could be made near the river banks. With this done, the Chu army withdrew in triumph.

A MEDITATION ON MARTIAL POWER - 止戈为武

Zhuang added: "War is not solely a demonstration of martial strength, but it should be about prohibiting violence and assuring stability to the people." He further stated: That (Demonstration) of Martial forces should be only pursued under 7 conditions: none should be violence in itself, rather it should be about: 1. prevent violence (general), 2. prevent war, 3. preserve the state's strength, 4. to secure victory, 5. to stabilize society, 6. unite the people, and 7. develop the state's economy.

Then, Zhuang contemplated the world Wu 武~ which in Chinese is literally translated as "Martial" and contemplated force- especially martial force in general and reached an epiphany. Zhuang remarked that the word wu/ "Martial" is composed of 2 letters combined together. That of Gē 戈 which literally means the dagger ax blade at the head of a halberd and Zhǐ 止 which means "Only" or "Only absolutely necessary." the realization that "martial power" is composed of "only (when)" and "dagger ax/ blade" lead him to express the saying: Zhǐ gē wéi wǔ 止戈为武 "Martial power is (using) the blade as a last resort" or "(Weilding) The blade when only absolutely necessary is true strength."

Ge Dagger-Axe blade with tiger engraving from the Warring States period.

止戈为武 could be interpreted as a reflection on restraint and confidence. In later eras- especially in notes related to Sun Tzu's "Art of War" this concept is further examined through the inferred idea that real martial arts (or military achievement) lies in the awareness that violence is only reserved when its absolutely necessary. Another interpretation- especially through the "Art of War" is that real martial arts lies in the ability to make the opponent submit without using force.

How strange- and how totally uncharacteristic, that the once headstrong young King who arrogantly suggested that all of his soldier's collective dagger- axe blade could metaphorically topple the Zhou kings' vessel would one day capstone his most resounding victory with such a humbling and sobering realization???

ARISE- THE THIRD HEGEMON

Chengpu and Bi visualized 凹凸. Like other points of contrasts the 2 battles showed diametrically opposing symmetry. Where as the resounding Jin victory in 632 BC was characterized by skillful flanking maneuvers that annihilated both of the Chu arms. Bi (597 BC) in contrast was a concentrated centralized assault that knocked the Jin forces with the momentum of its concentrated charge.

Bi laid the foundation for the climax of King Zhuang's career. After Bi- Jin faced a myriad of internal problems which forced it to take its attention away from Chu. First, a massive rebellion among its Di barbarian population erupted in the duchy's northeast- breaking nearly half of the state away. They had to spend the next several years stamping it out. Then a series of palace intrigues also tied Jin to focus internally- leaving Chu with the initiative to expand its influence unchallenged into the rest of the Central States. By now, King Zhuang was both feared militarily and highly respected by his lordly peers. Externally, he conducted himself as a gentleman, and was characterized by temperance and magnanimity.

Zhuang soon became the peace broker and mediator of the Central Plains. Two years after Bi- in the nineteenth year of King Zhuang's rule (595 BC), Zhuang led an army and encircled the defiant Jin proxy of Song for nine months, In the end, Song was forced to form an alliance with Chu and Chu retreated. With Song under its wings- so came the rest of the Central Plains states. Lu and other small countries successively attached themselves to Chu's orbit as vassals. Thus- King Zhuang reached the zenith of his career and Chu Hegemony was established.

FINALE

King Zhuang lived to an old age, but in his age, he became wracked with worries. Deeply aware that he was a one of a kind type of monarch- rare even among the best of his age, - and also having realized he had already achieved the zenith of his power, he spent the rest of his reign worried about a world without him and his eyes for talents. For he was the lone bird that soared and none could match his height. Before his death it was recorded that King Zhuang lamented to his ministers that none he knew could fill his void and secure Chu's power. And even in his last days, he was troubled that he had found no one who could continue his rare combination of improvisational dynamism, charisma, and grit to shepherd Chu when he leaves the stage.

Music: Destroy the Collosus

Sadly, King Zhuang's last predictions was also right on the mark as well. In the decades after Zhuang's death, Chu's national power rapidly waned and was again overtaken by Jin. Within Chu- massive infighting between the royal family members and factions of powerful ministers led up to a bloody purge where many ministers and their entire families were slaughtered to the last. Chu began to fall, and to make the matters worse, under the support of Jin- a once practically insignificant frontier backwater state wiped out the once universally dreaded- Chu army. Then within merely few years after that- Chu not only completely withdrew from the ranks of hegemony, but nearly half of the kingdoms would be over taken by that most insolent backwater vassal.

But alas one should not expent too much tears on the crumbling state of Chu. For the tale of Chu's destruction from the height of hegemony to the brink of ruin is also one that is worthy of our interest and laid with piquant details. I ask you to return to see that story- next time when we cover the destruction of Chu from the perspective of its destroyers: the insignificant backwater itself. For there was born~ the Next Hegemon, and leading his army to victory was none other than Sun Tzu himself.

Thank you to my Patrons who has contributed $10 and above: You made this happen!

➢ ☯ Muramasa

➢ ☯ MK Celahir

➢ ☯ Kevin

➢ ☯ Vincent Ho (FerrumFlos1st)

➢ ☯ BurenErdene Altankhuyag

➢ ☯ Stephen D Rynerson

➢ ☯ Michael Lam

➢ ☯ Peter Hellman

➢ ☯ SunB

Comments

It is noteworthy to point out the rather well- deserved collective animosity toward Chu~ and show how Chu conducted itself with smaller states: there was an anecdote related to King Wen of Chu (son of the 1st King of Chu: King Wu.) Wen heard that the nearby lord of Xi had a peerlessly beautiful concubine, King Wen- intrigued, asked to visit Xi with guard units under a pretext of a friendly stately visit. He was warmly welcomed by the ruler of Xi- his host. However once inside Xi, the Chu army invaded the state and vanquished it. Then King Wen took lord's concubines for himself. Thus it is not hard to see why Chu was nearly universally distrusted by other Zhou states~ and why the Kings of Chu were seen as debauched kin- slayers and backstabbers who must be put down. Ever since King Wu dared to transgressively call himself King, for that impudence alone, Chu was marked for total annihilation. Political blowback toward Chu could also be examined through the values of the Zhou and Chu peoples.

Zhou's highly ritualized Li (riteousness) minded warfare, the goal of conflict usually revolved around achieveable goals, such as submission and clearing of past grudges/ slights. Wrongs are corrected in the form of restitutions, tributes, - at worst, lopsided marriages, vassalage, submission etc. But at the end of the day soverignty was almost never an issue. Very rarely would there be complete annexation. However when it came to Chu- Chu invaded its neighbors with the outright intention of annexation, displacement or slaying of the neighborly state's ruling house. These are seen as savage actions, and a long century of this continual and stubborn refusal of Chu to change their ways hade made the Hegemon's de facto duty in stomp out Chu and protect the small Zhou states.

That said, if ancient Chu language is a Tibetan Burmese language I would not be surprised.

Tibetan Burmese language in general was quite close with ancient Chinese and ancient Chinese has a lot of n' sounds and was much more tongue heavy.

What else can you say to assert your claim that they are related? Now I'm quite curious,

The Chu and their relationship to Zhou Civilization reminds me of the relationship between Slavic Russia and the Holy Roman Empire of Western Europe. Similar, but different, and defiantly separate. When Russia threw off the Mongol Yoke and gained independence the Holy Roman Emperor offered the Russian ruler a title since he was theoretically the ruler of all Christendom. The Russians rebuffed this offer and rejected the jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Emperor and declared themselves Czars, their own Caesar fully equal to the Holy Roman Emperor, and Russia is her own Empire ... emperors in their own right, indicating they did not need any permission from their western cousins, especially given the fact Western Catholics and Eastern Orthodox regarded each other as schematics.

The Chu went from Viscounts, subordinate in the Zhou feudal order to Kings in their own right, fully equal to the Zhou Kings. How arrogant !! did that indicate the Chu no longer considered themselves apart of Chinese civilization? did they have ambitions of their own Empire like the Russians??

Nor are you alone in thinking that Spring and Autumn politics have some similarities to that of the HRE, the Central Plains states and many other regional blocks also bore some reminiscence to the Imperial Circles in the HRE.

Like Russia, Chu was both huge in territory and was seen as only "partially civilized" and are in fact a cultural other (the horrors of the east for the Russians in the eyes of the rest of the Europeans and the tendrils of the southern barbarians in regards to Chu) Chu was so large that it was able to diplomatically be very assertive while no other Central State was large enough to contend with them, therefore they had to rely on Jin ~ realm police/ global police in a policing role that that of the US today.

In fact just as I was writing this I contemplated the similarity between King Zhuang and Peter the Great, both are curious rulers who managed to both greatly conquer their periphery while aggressively adopting the established cultures of the so called "civilized" states. After the matter is done, they were able to resoundly beat their rival- the former Hegemon of the region and hold hegemony over these whole swaths of lands. (Chu by the early Warring States period would became so huge that it was the size of half of the Zhou world.)

The determination of rank before the Spring and Autumn period- in the wake of the founding of Zhou and Duke Wen's distribution of titles was largely in relation to the blood relations to the Zhou royal family. Lu, Song, and Jin were all branches of the royal family.

In other case, they are elevated because of great services to the royal family. For instance Chu was elevated to Viscounts because its patriarch was once the tutor of the Zhou lords before they took the throne for themselves- an usurpation that Chu actively aided. As for QIn- they were granted the Duchy because they aided in escorting the Zhou King's exodus to Luoyang and were given rights over the lost lands in the West to hold as their own.

Hmmmm, interesting, many Chu words are completely different from the Sinitic languages of the Plains, including basic words. It's possible that this is true.

Can you tell me where you heard that before and provide some sources so I can look into it?

From Wiktionary:

虎 (/qhlaaʔ/ in Old Chinese)

"From Proto-Sino-Tibetan *k-la (“tiger”), from Proto-Mon-Khmer *klaʔ (“tiger”). Cognate with 菟 (OC *daː) in 於菟 (OC *qa daː, “tiger”)."

虎 and 於菟 are cognates of each other, but it seems that this word was borrowed into the Sino-Tibetan as a whole at a very early stage so both 虎 and 於菟 were loanwords from the Austroasiatic family

Owing to the fact that the Central Plains are just endless flatlands its not surprising that it could be conquered by a spillage of people from the west.

Back then- the early spoken Chinese didn't have tones, and are quite similar to Tibetan, with a lot of ŋ nasal sounds symbolized by the agma ŋ sign and initial consonant clusters. It's very heavy. Where as we already know that Austronesian speakers inhabited the east coast region in what is today's Shanghai. The Kingdom of Yue and Wu were both culturally very distinct, with tattooed tribesmen similar to the later Austronesians and spoke with their distinctive language.

But the poems from that period, circa Spring and Autumn Period no longer rhymes in modern Mandarin but it does in Cantonese. I've always thought the southern Chinese dialects were closer to the older forms of Chinese, sort of like Quebecois French is closer to medieval French than modern Parisian French. Colonial societies like Jiangnan in southern China or French and English in North America preserves the older forms of speech.

Teochew's pronunciation still has a lot of ŋ sounds- especially when trying to pouncing anything that has to do with the "Wu" sound, in that form, and in old Middle Chinese and Old Chinese Wu- of Five 5, or kingdom of Wu and Wu- as in Martial sounds like "ŋu" ~ a very heavy NUu sound. In many expat Chinese Nanyang communities there's people still with last names that's spelled Ng (like Nigel Ng, the comedian who played Uncle Roger) and Dr. Wu Lian de, who invented the N19 Mask during his fight with the Pneumatic Bubonic Plague in 1911- his name in local dialect is rendered as Ng Leen Tuck.

Modern Chinese- "Mandarin" in English, or "Putonghua" is actually the courtier's dialect "Guanhua" (lit "Official's speech") of Beijing with a heavy Manchu influence. Ming Chinese is very choppy- so words that are originally read as Ga or Za- after the Manchu influence is pronounced Gah or Zhah. *Until the 1980s most region of China has extremely strong accents and dialects and are not very intelligible to those from distant regions. However, they'd have no problem writing to each in long essays and easily understand exactly what they are saying.

TL:DR: Old Chinese used to be very tongue heavy and sounded more like Tibetan and Burmese, however over time it became choppier. However this trend is bucked again with the Manchu- influences. In which Chinese- especially northern Chinese became very heavy with Rrrrrrrrrrrrr sounds again.

"Modern Chinese- "Mandarin" in English, or "Putonghua" is actually the courtier's dialect "Guanhua" (lit "Official's speech") of Beijing with a heavy Manchu influence. Ming Chinese is very choppy- so words that are originally read as Ga or Za- after the Manchu influence is pronounced Gah or Zhah."

This is a very popular misinformation and stereotype. Nomadic languages have almost no phonetic influence on Northern Chinese languages. This is because a lot of the sounds in Mandarin are non-existent in those nomadic languages.

Nomadic influence is mostly limited to loanwords, with the exception of a few grammatical traits. Northern Chinese, or Mandarin, had already taken shape by the end of the Song dynasty.

Ming-era Northern Mandarin, or the precursor to Putonghua, existed in parallel with Southern Mandarin, as do their modern counterparts (Jilu Guanhua, Jiaoliao Guanhua, Xinan Guanhua, Jianghuai Guanhua), and would already sound similar to modern Northern Mandarin, meaning that Northern Mandarin had already dropped 入聲 by the time of Ming.

yeah no, you are right, its really bipolar in the weird combination of the robust and the delicate. You can totally tell which is which- and that it's very incongruent in how they are supposed to be. I guess I based a lot of my references from post- Qing figures like Puyi and others, and their way of talking it's pretty much modern common. Some of the KMT nationalist movies also sounds like modern Putonghua as well. Although both Mao and Chiang has regional accents.

But 老國音 is really disconcertingly strange. Such a hard meld

The original Chu language is not sure which language it belongs to,but for most of the time it was very close to the Khmer language.

A small number of scholars believe that the original Chu language is the Tibetan Burmese language. (probably because the Chu people's initial territory is close to the territory of “伊洛之戎”.)

I find it interesting King Zhuang of Chu after his victory over Jin made his men drink from the Yellow River, made his horse drink the waters and he himself drink from this river which is the mother of Chinese civilization. It seems very sentimental, as if he's proving they are returning "home" or place of origin. It's like 4th generation Italian- or Irish-Americans returning to Italy and Ireland and trying to reclaim something lost, returning to their "roots" when in fact they are Americans and have little in common with Italians and Irish. Is it true that the Chu had their roots in Zhou or was it just propaganda? Was trying to become Central Plains gentlemen and nobles really that attractive? if they did have Tibetan, Khmer, Burmese, Austronesian origins, why not celebrate that? why try to coopt Zhou Central Plains civilization? When the Germanic Barbarians overran the Western Roman Empire, they came to admire Latin civilization, converted to Christianity and Charlemagne even called himself 'Emperor' and Augustus. But they didn't forget their Germanic roots, they didn't start wearing togas, adopt Roman names and tried to recreate ancient Rome. The Chu on the other hand converted wholesale to Zhou civilization it seems, giving up all their 'native' characteristics.

1 is that yes, Chu actually did have a history that is long enough that it stretches before Zhou's ascension, but its largely semi- mythical, *and- like with many of those origin stories its hard to confirm and are probably later insertions to attach themselves to an illustrious ancestor and bolster their claims. *After all, fabricating claim is not only common in medieval CK2 era but throughout many systems whose title's powers are derived from claims to blood and lands. In the tradition of Chu, they were descendants of the Fire God Zhurong~ a claim that no doubt would allow them to associate themselves with the Yellow Emperor and Yan Emperor by blood. In a world where powerful blood is power and powerful tradition of such blood clans is power it is only natural to try to weave and coil around those stories,

2. If you are shocked by Chu's conceding cultural assimilation (not even a full one btw for even until the last days of their Kingdoms they were odd balls compared to the rest) ~ when you get to my next chapter, which covers Wu, you'd be much more surprised. They practically dementedly adopted Central Plains culture overnight despite being tattooed Yue people that were virtually outside of the Chinese cultural sphere. They even claimed (almost a complete fabrication) that they were descendants of Zhou royal claimants who self exiled themselves to the east coast. Despite the fact that Wu and later Yue's culture had not much similarities with Zhou culture before that point. The way Wu immediately adopted Zhou culture was as if some cargo cult Pacific Islander~ upon first contact with the west quickly began to wear cowboy hats, dress like gun-slinging ranchers, and talked about how his ancestors were a lost Tribe of Israel. It would be highly comical, if not- from the perspective of Chu, an absolute and unseen nightmare.