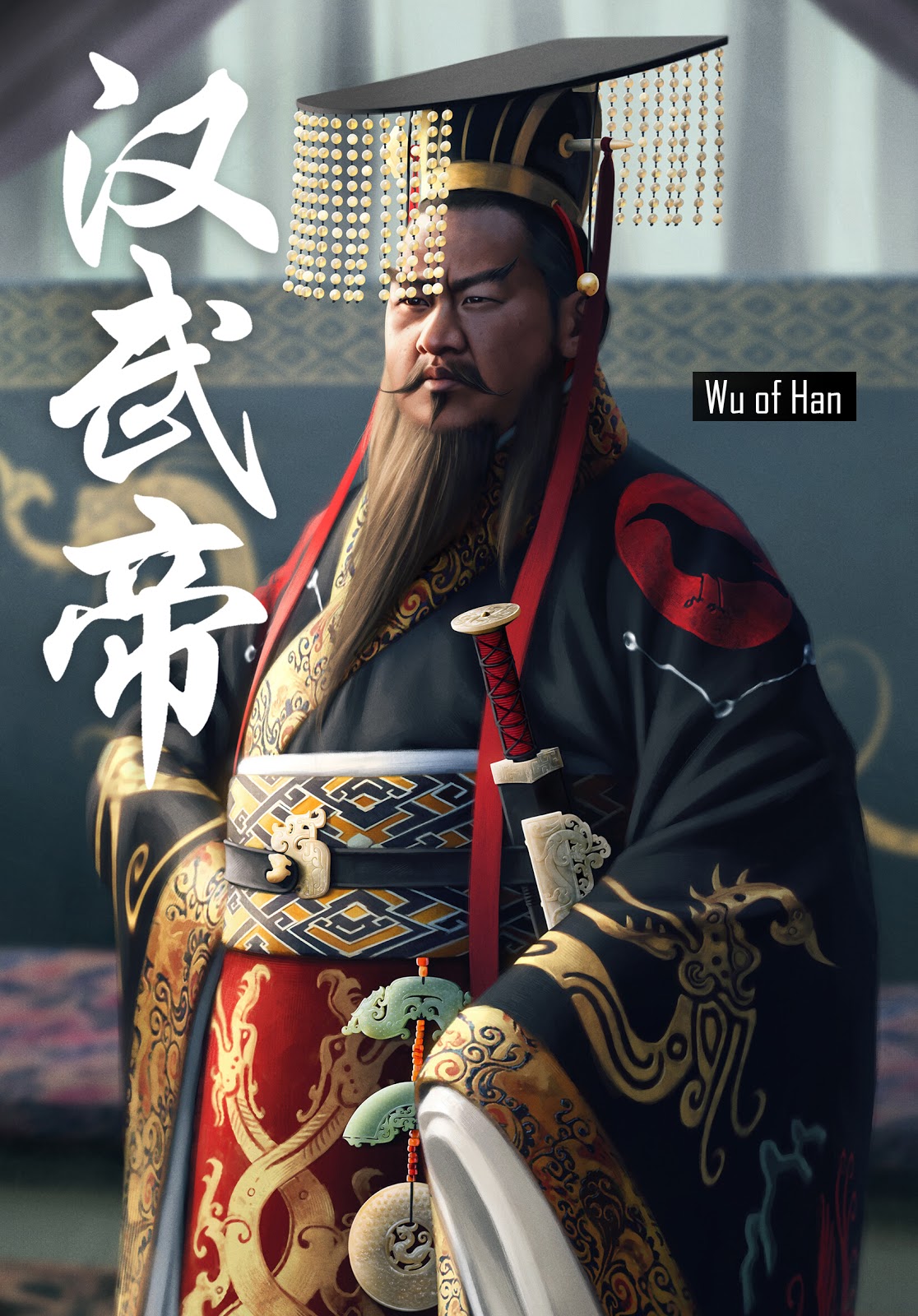

Emperor Wu of Han: 汉武帝

The middle aged Emperor Wu at his prime in his Mianfu (Hanzi: 冕服, pinyin: miǎnfú), lit. "Coronation Costume", a formal cloth worn by emperors and royal family in special ceremonial events such as coronation, morning audience, ancestral rites, worship, new year's audience and other ceremonial activities. Symbols of power- ranging from the 3 legged crow and the twin celestial dragons are prominent displayed on the robe. His steel sword is fastened to his belt with an ornate jade belt clasp.

Original Artwork by: Joan Francesc Oliveras Pallerols

A ruthless but also ruthlessly efficient autocrat. Han Wudi, or Emperor Wu of Han's long reign lasted a remarkable 54 years- a record not broken until the reign of the Kangxi Emperor more than 1,800 years later and remains the record for ethnic Han Emperors. During his tenure, the Han state went from a respected but still restrained power to the foremost one in East Asia.

His half century of aggressive expansions in all directions resulted in the Han effectively doubling its size. At its height, the Empire's borders spanned from the Tarim Basin and the Fergana Valley in the west, to central Korea in the east, and to northern Vietnam in the south. His posthumous honorific: "Wu" 武 ~ (Literally Translated as the "Martial One" or the "Warrior") by his successors, was attributed in regards to his vigorous campaigns.

In due course, Wu's half century of campaigns would not only force many confrontation with the powerful Xiongnu Confederation but also push the Han to expand in all of its directions. Thus, an inextricably linked legacy of a stern warrior king and his long wars was formed.

Young and voracious. At the age of 15, Liu Che- the future Emperor Wu ascended to the Han throne. To mark his early reign, Liu embarked on a series of reforms to strip various factions from power and reorient the state apparatus under his personal direction.

Music: 神人畅 Enchanter's Song (Han). Rearranged Han Guqin music

REBELLIOUS REFORMER

By the time of Wu, the Han was still somewhat of an inward looking state. Although there is great prosperity in the empire, there were periods of great rebellions committed by the various imperial uncles who held great swaths of feudal territories. Wu's father Emperor Wen spent much of his career dealing with such internal disturbances and curtailing power from his ambitious kins. On a horizontal level the nobles and great merchants of Han also held great sway in the court. Thus Wu's first priority consisted of protecting himself from such power blocks.

When the young Liu Che- the future Wu of Han ascended the throne at the age of 15 , his first reforms were directly aimed at curtailing the power of the extant conservative Han nobles while streamlining and centralizing the state's functions directly under his own rule. However, the majority of conservative factions- especially under the direction of his conservative grandmother at court blocked many of his reforms.

Sidelined, because of Liu Che's ambitious reforms, many resentful nobles coalesced around Liu Che's grandmother Empress Dowager Dou, who held true sway in the court.

THE REINS OF STATE- ENEMIES

These factions went as far as having his chosen advisers framed and forced to commit suicide. Plans were also hatched by the nobles to remove the troublesome Liu Che from power and rotate in his more controllable relatives in as replacement emperors. Because of his bitter resentment at having been obstructed from truly ruling his state, the young Liu Che often snuck out of the palace dressed as a idle aristocrat to observe his capital.

These worldly experiences eventually made him realized that he could recruit a new pool of loyalists completely from the ranks of commoners. Thus, secretly, Liu Che began to gather many commoners under his patronage who are entirely loyal to him. In 138 B.C. An opportunity presented itself to Wu to flex his imperial muscles.

KINGMAKER

Southern China during the early Han period. At the time of emperor Wu's accession to the imperial throne, there were many small Yue kingdoms beyond Han's southern boarders. The smallest of which- Ou'yue (yellow,) later known as Dong Ou, was aligned with the Han. When the more powerful kingdom of Minyue invaded it and slew its king, the Han was invited to intervene on Ouyue's behalf- thereby providing the young Emperor Wu with the opportunity to maneuver himself back to imperial power.

During the early Han emperors, what is now modern Zhejiang around the area of Shanghai was not in direct Han possession. Rather, much of the area south of the Han boarders was a patchwork of minor kingdoms largely inhabited by the native Yue people (some with sinicized Kings etc collectively know as the Baiyue, or "Hundred Yues") When the small Yue kingdom of Ouyue 瓯越- a Han dynasty vassal was invaded by the bigger Yue kingdom of Minyue to its south, the King of Ouyue was slain in battle.

Desperate, Ouye sought Han military intervention against its powerful neighbor. Although Liu's grandmother still held the sway of the court, Liu Che bypassed her control and slew the local Han garrison commander and replaced his command with that of a loyal court ambassador. The Han garrison there then dispatched a massive navy against the Minyue and forced them to retreat from the Han allies. The refugees of Ouyue thereafter pledged themselves to be completely incorporated by the Han for permanent Han military protection. Thus Wu achieved a great political victory. Not only was a former client willingly brought into the imperial fold but Wu had achieved all of it without the oversight of his grandmother. He had acted like an emperor.

POWERMONGER

Music: The Eternal Empire (Drums)

With the imperial army under his direct influence, the rein of state was truly his. After 135 B.C, Liu took the sole reins of the state without the oversight of regents. When his grandmother died, Liu Che actively began a series of reforms to destroy the obstructionist power blocks. To achieve such means, he stripped obtrusive nobles of power and elevated many capable commoners to positions of great prominence (ones naturally would be indebted and wholly loyal to him) Wu then transformed his bureaucracy to that of a highly meritocratic one. He would never be sidelined by his own nobles for the rest of his reign.

These vertical consolidation of power achieved two things, 1. a newly unobstructed channel for Wu to grasp the rein of the state, and 2. a clever purging of obstructive conservative nobles and stacking their vacant position with capable loyalists entirely indebted personally to the emperor. It was also a flexing of the young emperor's political muscles. Not only did he prove himself to be his own man by these actions, but also marked his future as that of a willful visionary, one who would take the Han toward new directions with- or without the approval of his court. These are the foundation of Liu Che's stern and autocratic style of rule.

From 138 B.C onwards, Emperor Wu took the position of a kingmaker and mediator in local Yue political struggles. For the next 20 years, Wu keenly observed the various Yue kingdoms with vulturine hunger. In these local matters, the quarrelsome state of Minyue usually (ironically) became Wu's best boogieman in local affairs. Whenever the aggressive Minyue attacked its worried neighbors, these desperate states would beseech the Han for reinforcements and support. Under the pretext of punishing the Minyue, Wu would slowly slice apart Minyue while at the same time incorporating various Han vassal kingdoms in the area to be fully under Han control. By 111 B.C- after 27 years of maneuvers. Wu annexed the rebellious Minyue and extended Han dominion as far as Vietnam in its south. However, during these decades, the majority Wu's focus shifted northward against a much more deadly (and unified) mortal threat, perhaps the greatest threat ever faced by the Han dynasty since its founding: the Xiongnu.

Music: Scourge of God

THE HAN- XIONGNU WAR

For millennia before Wu, the settled Chinese states have faced seasonal raids and incursions from the nomadic tribes from the steppes. By the time of China's first Emperor- the many tribes coalesced into a great power and formed the mighty Xiongnu Confederacy. Led by a powerful Chanyu (King), the Xiongu vigorously expanded in all directions and became the master of the steppes. Their impact was such that the first Emperor attempted to link up all of northern China into the mighty Great Walls.

However Qin's death and the dynasty's collapse resulted in further invasions. Han's founder, Liu Bang famously faced off against the great Modu Chanyu and was resoundingly defeated. There after, the Han was forced to pay a (as stated by Han sources) humiliating annual tribute to the Xiongnu and also- provide an imperial princess as a wife whenever a new Chanyu ascended to the throne. This eventually became the diplomatic norm for a century between the Han and the Xiongnu. However, despite this arrangement, there were still many instances of skirmishes and raids into Han territories.

FROM APPEASEMENT TO OFFENSIVE

WAR REFORMS

When the young Emperor Wu ascended to the throne, on external matters, he sought to end the tributes and the Heqin marriages to the Xiongnu. To plan for the day of reckoning, Wu dispatched his envoy Zhang Qian westward in 139 BC to seek an alliance with the various unknown Xiongnu vassals outside of Han's orbit, including the states of the Tarim Basins and that of the Yuezhi of Kangju (modern Ferghana Valley.) This resulted in the first official instance of Chinese exploration into Central Asia.

A royal debacle: At the frontier city of Mayi, Wu setup an ambush to assassinate/ capture the Chanyu. After sending an influential merchant to pretend that he had the city in his possession- and was ready to give it to the Chanyu, the Xiongnu were lured to come and officially take possession of Mayi. However, the sharp- minded Chanyu noticed that the whole area was eerily empty, sensing a trap, he sent out scouts which detected many Han legions in waiting. After abducting a Han scout and learning of Wu's true intentions, the Chanyu fled north- while the heavy Han chariots were unable to pursue the nimble horses. Mayi demonstrated the lack of mobility for the Han army.

After an embarrassing failed ambush against the Chanyu at Mayi in 133 B.C- whereby total war was declared between the two empires, Wu sought to radically reform the Han army. Analyzing the failures of the previous Han ambush, Wu concluded that the Han's army was both too cumbersome and lacked inventive officers.

Music: Into the Fray

YOUNG HORSES AND YOUNG OFFICERS

Thus he radically reformed the army, he phased out most of the cumbersome chariots which acted as the mainstay of the Han mounted troops and created true nimble Han cavalries, he also dismissed many of the conservative office core and hired younger, innovative and hawkish generals to lead his norther campaigns.

2 Reconstructed suits of Han dynasty armor. Han dynasty armors are frequently attached to pauldrons. The heavier armors have a full armored sleeve to protect against the usually vulnerable armpits of the lamellar wearer. Many Han armors, such as the 襟领铠 Jīn lǐng kǎi, "Collared" lamellar armor also have raised back and side collars to protect against glancing sword slashes towards the wearer's neck.

Realizing that the Xiongnu were poorly equipped to be on the defensive and cannot easily replenish their own slain soldiers, Emperor Wu used the Han Great Walls as his line of projection beyond the north. From these walls, he stockpiled for the long campaigns. The army would be well supplied for a long expedition. The core Han infantry would be supported with massed crossbowmen. For protection, many mounted crossbowmen were deployed in support of the infantry forces. In the Western Han period, these served as the majority of Han cavalry. Unlike bowmenship, which takes a life time to perfect, the crossbow as well as its trigger mechanisms are very easy to use by even the simplest of peasants.

Heavy chariots were also deployed in the Han columns. Although they were beginning to be phased at this point, in the wide flat expanse of the steppes these heavy chariots/ and supply carts could form lines of defensive barriers to protect the Han soldiers from Xiongnu volleys and charges. Thus arrayed, the Han attacked north of the Great Walls.

Music: Warriors

WU'S VICTORIES- BATTLE OF MOBEI

Under the capable leadership of new generals like Huo Qubing and Wei Qing- in conjuncture with the newly reformed Han cavalry, the Han achieved a series of victories over the Xiongnu. In the Battle of Mobei, massed Xiongnu hordes of the Chanyu assaulted the Han forces in a deadly confrontation. Realizing the Han forces are at a major disadvantage being caught in the open flat lands, Wei Qing immediately ordered his chariots to deploy into a defensive line, where by his soldiers could take cover behind it and fire back.

Han dynasty relief depicting a Han mounted crossbow man pursuing a Xiongnu warrior firing backward from his saddle.

Then, a sandstorm swept through the battle field. Wei- realizing that the storm camouflaged his soldier's ranks and also prevented enemies from coordinating their assaults, took advantage of the weather and counter attacked. Using the storm as a screen, the deadly onrush of Han cavalry eventually broke the Chanyu's army and the Han won the day. The series of victories achieved by Wei Qing and Huo Qubing allowed the Han to sack the Xiongnu capital and return in triumph to the Han.

Fought in a sandstorm, the Battle of Mobei (119 B.C) saw the Han forces project north, until it was met by large horde of mobile Xiongnu cavalry archers. The Han soldiers took refuge behind their screens of chariots until a sandstorm allowed them to counter- charge the Xiongnu and scatter them from the field. The battle was massive in scope and by some estimates the combined armies amounted to more than 300,000 soldiers in the day long battle.

Han tomb relief depicting wars between Han soldiers and Xiongnu horse archers. Han soldiers are distinguished by their dotted scale armor surcoat while the Xiongnu are marked by their distinctive conical cap and recurved bow.

RAPACIOUS NEEDS, DIPLOMATIC EXPANSIONS

Although battles like Mobei proved a major victory for the Han- economically, it proved crippling to the state. By Han's records hundreds of thousands of their horses and cattles were lost, scattered by the dust storm and accounted for nearly 80% of the horses in Wei Qing's army. An amount that was unimaginable to replenish during the Han, especially considering that the heartland of China proper's terrain is not ideal for breeding horses. The extreme and crippling demand for horses and coffers of war soon forced Emperor Wu to look elsewhere to supplement his endless need for war fodder.

Middle aged Emperor Wu at his prime. After his initial victories against the Xiongnu, Wu spent the next few decades on consolidating his advantage over the dynasty's mortal foe. In the struggle, Wu shifted his attention westward to detaching various smaller Xiongnu vassals from their yoke.

The Han would spend the next 30+ years in a continual struggle with the Xiongnu, although Mobei proved a vital victory, the Xiongnu were far from being beaten. An accurate description would be that both empires were severely bloodied and economically shaken. In response to his war aims, Wu was forced to levy new taxes which greatly burdened his populace. The tax measures were so harsh it impoverished whole regions in the empire.

Though the Han won, each victory came at that of a figurative limb. At the rate of Mobei and other crippling expeditions the Han would attrition itself to death from such strings of victories. On military matters, Wu was a bloodletting overseer. Quick to expend lives, and often did not tolerated any failures, but most of all, he doggedly and relentlessly applied pressure on his foes until they cracked. Though outwardly unimaginative, perhaps Wu also knew all along the greatest asset of his empire's strength, the Han's ability to afford sheer numerical and economical losses while the same would cripple those of its beleaguered enemies. His empire could afford to grind his enemies to death while keep taking otherwise mortal blows.

In order to shore up his urgent need for war horses, Wu instituted a national horse breeding program, where by the state would lend horses and ponies to be raised by farmers. Using tax incentives, Wu sought to make the empire into his stables. This eventually provided Wu with hundreds of thousands of new horses but even these were not enough for his war aims. Keen to explore all of his options, Wu remembered a detailed report from his returned diplomat Zhang Qian: which described mysterious western kingdoms with magnificent "Heavenly Horses" that sweat blood. Due to these dazzling reports. Wu set his sights firmly on the western kingdoms that served as the Xiongnu's western vassals.

Detail of Wu's court attire. Fashion largely inspired from the robes from Mawangdui Tomb Complex of Eastern Han.

Music: Thirsty Sands

WESTERN EXPEDITIONS

Around the explosion of the Han- Xiongnu War, Wu's diplomat Zhang Qian returned from his western tour in 125 BC with detailed news for the Emperor. His reports showed an array of sophisticated civilizations that existed to Han's west, with which China could advantageously develop relations.

Zhang Qian's western overtures were filled with disappointments. After spending years as a Xiongnu prisoner, Zhang finally escaped and made contact with the Yuezhi vassals of the Xiongnu. However, they utterly rebuffed his suggestions for a Han- Yuezhi alliance. Despite the failures of his initial mission, when he returned to Chang An Emperor Wu made great use of his western accounts and thereupon formulated his western policies.

Original Artwork by: Joan Francesc Oliveras Pallerols

The Oasis kingdom of Loulan- served as the entrance into the Tarim Basin. Then a Xiongnu vassal. Emperor Wu subjugated the kingdom as a vassal in 108 B.C and his descendants later fully annexed the kingdom. The city would remain a key Han dynasty city in the Basin until the 2nd century CE.

Macedonian Companion cavalry from 2 centuries before the War for the Heavenly Horses

Original Artwork by: Joan Francesc Oliveras Pallerols

In revenge for the killing of his envoy, Emperor Wu dispatched a massive punitive expedition against the obstinate city-state. The first invasion ended in failure due to attrition and lack of supplies to sustain the siege. Unsatisfied, Wu then dispatched a much greater invasion force with full complements of siege weapons and supply wagons.

The massive Han legion over- awed the various kingdoms of the Tarim Basin and the relentless Han invaders dismayed the gentry of Alexandria Eschate so much that the nobles of the city slew their king and sent his head to the Han besiegers~ promising that they would provide as much Heavenly Horses as the Han required. After setting up a Pro- Han vassal in the city and securing the pastures of Ferghana, the Han forces marched home.

Thence, Emperor Wu's insatiable need for war horses was finally satisfied. With these highly prized Heavenly Horses, the Han secured long term victories over the Xiongnu. Not only was the Han able to outproduce men and equipment than their foes, but it boasted a bigger economy, well supplied generals and now the best war horses in the orient. On top of which, the Han also deprived the Xiongnu of their key vassals and monopoly over Central Asia.

THE SILK ROAD OPENS

For the next 3 centuries, the Han would become an active player in the politics of Central Asia. An inadvertent side effect of these social- economic changes was the formal establishment of the Silk Road. Noticeably, the Han acquisition of the newly conquered western regions coincided with the establishment of the Kushan Empire in India and Central Asia, Parthian Empire in Iran and the Roman Empire in the Mediterraneans. For the 1st time in Eurasian history there were 4 major overland empires directly connected from one ocean to the next- and wherein goods could freely travel from one extreme end to the other.

A BANKRUPT & PARANOID FINALE

Music: Red Forest

By the age of 50, Liu Che had spent nearly his entire reign in war and kingmaking. Since his accession of power in 135 B.C, Wu had pursued a constant series of protracted wars that spanned several decades. All of which came at a crippling cost to his citizenry- by Wu's late reign, the empire was at the brink of bankruptcy. In domestic as well as external affairs, Wu was characterized by his forcefulness. Wu expected results and obedience, and usually when both are not met be would become suspicious. He frequently executed commanders who failed or he suspected of disloyalty. Including once wrongfully exterminating a general's whole clan because of false accusations. This was made much worse when one of his respected courtiers protested this and Wu had him castrated. The courtier was none other than Sima Qian, the father of Chinese history and the author of the "Record of Grand Historian," who was instrumental in recording what we know of China's history from the earliest mythical times until the reign of Wu. Sima Qian would bear a burning resentment against Wu for the rest of his life.

Because of Wu's paranoia, soon a caste of officials began to actively stoke the emperor's suspicions to use them against their own political rivals. Whereever there was smoke, they made sure to point to supposed "fires," even at times resorting to creating the fires themselves. These officials purposely spread rumors there were spells of witchcraft against Wu at every corner.

THE TRAGEDY OF THE CROWN PRINCE'S REBELLION

Ironically it was also Wu's paranoia that destroyed his best chance for a stable legacy. When Wu was in his 60s, false rumors by jealous officials convinced Wu that his talented son Prince Ju was (falsely) staging a rebellion against him through witchcraft, Wu believed their lies and ordered Ju's "rebellion" to be swiftly put down. Thus, his innocent son and his mother Empress Wei were forced by none other than Wu to rebel against him. The two sides battled in the streets of Chang An for five days until Ju was driven out of the city. There after, Wu began to purge nearly everyone he suspected of having connection to his son's "rebellion."

Prince Ju's immediate family members were all executed, his mother Empress Wei committed suicide, and many suspected sympathizers were all killed. Only Prince Ju's infant baby was spared of death due to his age, however he was still thrown in prison. A friend of Prince Ju eventually revealed to the emperor of Ju's innocence, but by then many of the emperor's devoted (and characteristically efficient) local officials had cornered Prince Ju. In order to spare his followers of danger Prince Ju committed suicide, but his followers were still slaughtered by the officials seeking rewards on behalf of ridding the emperor of his enemy. Ironically and characteristically, although saddened by Crown Ju's death, the autocrat had to reward his loyal officials. One simple lie undid Liu Che's best laid plans for an heir. There after, Wu further retreated into solitude.

...AN APOLOGY?

However, unlike many despots across the arc of human history, what Wu did next was uncharacteristic of the long image of himself. With solitude, Wu also gained the perspective that the rumors of witchcraft were fanned by corrupt officials. Thus- retracing the details of their reports and cross examining his previous decisions, Wu was able to figure out on precisely which powerful officials had lied to him and manipulated him with their lies. Wu had those ministers ruthlessly killed along with their clans.

Music: Eternal Empire (Night)

Wu then publicly erected a palace and altar for the deceased Prince Ju's spirit to express his regret. In 89 B.C., emperor Wu released a document of self-criticism, known to history as the "Repenting Edict of Lun Pavilion," 轮台悔诏 to publicly apologize to the whole nation about his past policy mistakes, his confusions, including his wrongful executions, the hardship he laid upon his people, and his bloody wars. Stating and wishing that soldiers return to their farm for their homes, corrupt officials stop tyrannizing the people, people be freely allowed to see their government officials with all sort of petitions and requests, and wars with the Xiongnu be finally brought to a (dignified) victorious end. Soon after, Liu Che, which had ruled as an absolute sovereign for half of a century died.

EXIT THE MATIAL EMPEROR

The Martial Emperor's final maneuvers was an unexpected one. And one that was almost uncharacteristic of his old self. Where as Wu was almost entirely characterized by stubborn forcefulness and unrelenting, irrefutable ruthlessness and tyranny. His last acts were one of sobriety and self- effacing humility.

As one of his final acts, he appointed Crown Prince Ju's friend and ally Tian Qianqiu 田千秋 as the newly appointed Prime Minister of Han. Tian was a peaceable man, and advocated for the Han veterans to be allowed to return home and promoted more lenient tax policies and agriculture. Under his recommendation, several agricultural experts were made important members of the administration. After the Edict of Lun Pavillion, Han's five decade long wars and territorial expansion generally ceased. Thousands returned home to finally enjoy the fruits of their bitter labors.

These policies and ideals were those supported by Crown Prince Ju, and was finally realized in spirit. Ironically and also unbeknownst to the late Wu- the late Prince Ju's baby son, who was thrown in prison since childhood, would one day also rise to become a Han emperor after Wu, and became one of Western Han's great sovereigns.

→ ☯ [PLEASE SUPPORT ME @ PATREON] ☯ ←

Thank you to my Patrons who has contributed $10 and above: You made this happen!

➢ ☯ Muramasa

➢ ☯ MK Celahir

➢ ☯ Vincent Ho (FerrumFlos1st)

➢ ☯ BurenErdene Altankhuyag

➢ ☯ Stephen D Rynerson

➢ ☯ Michael Lam

➢ ☯ Peter Hellman

➢ ☯ SunB

The life of Emperor Wu was striking in several ways. He certainly fit the stripes of stern and ruthless warriors kings like that of Edward I of England, Ivan the Terrible, and Peter the Great of Russia. An early life of insecurity suffered at hands of court factions. From whence they discovered their true security lies in proving themselves worthy of holding onto power. A worldly adolescence where they learned to be self made and willfully visionary. A career of expansionist wars and broad sweeping reforms.

A middle age of domestic tyranny and brutalization of their kin and heirs. Finally, a descent into despotism and paranoia, made lonely because of their streak of authoritarianism where they trusted none but themselves. *But- somehow, one of Wu's final acts~ in defiance of such molds of typical tyrants was one where he chastised himself and wished to undo his wrongs. Accompanied with a sobriety that called out the snake that coiled around him all his life. An unpredictable decision which puzzled Chinese historians and politicians on all sides of the political spectrum to this day.

![Various Mianfu worn by Zhou dynasty ]Princes and Kings.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjmxVVmr73iJwtyGmZukZTN2dN2sBUArneoK4aI8sMafl0SfYMceuS05rMJWuMf-rfF47mxyLgEcX2wy0tUO-yvjrDh4iaPQZl2vFf0vwKc5IwuFJ34CnJKw6KWFD90jQSJUkPS_tnFHVPW/s640/200014040_00010+o.jpg)

Comments

What are your thoughts about the theory that Sima Qian's biography of the First Emperor of Qin in his Grand History was actually a critique of Han Wudi, ... all the criticisms of the First Emperor's spending, wars, building the Great Wall, tyranny was all actually indirect criticism of Han Wudi himself and perhaps a way for Sima Qian to persuade Han Wudi to cease and desist his actions lest he and the Han Dynasty share the same fate as Qin.

It's an interesting theory but it would mean we don't actually know much about Qin Shihuangdi which is fascinating since we know so much from Sima Qian about the Qin Dynasty and the First Emperor.

But I can't blame Sima Qian that much either, I mean a lot of western scholars have dismissed his account of the scales of QIn's power, infrastructure and monument construction until the terracotta warriors were found beside Qin's pyramid. And that most scholars also dismissed Shang dynasty's existence at all until they discovered Yin at Anyang. Although the elements to support your assertions are there it's possible that he was merely stating the fact about both sovereigns whose reigns are largely defined by endless military conquests

Plus Sima Qian has other ways to destroy Wu and the Liu clan's reputation, his account of Liu Bang was quite unflattering in many instances and its possible he purposely propped up Xiang Yu as a sly against the dynasty.

↓↓↓

https://anthrogenica.com/showthread.php?20495-Ghazan-Khan-(Chingiz-khans-heir)-O-M175-ancientDNA

Hope this helps.

Lingchi was first seen during the Liao Dynasty.

Lingchi was legalized in the Yuan Dynasty.

Lingchi rose in the Ming Dynasty

Lingchi “flourished” in the Qing Dynasty.

But in the Tang Xuanzong period, the death penalty was almost abolished. Because the crime rate was too low, and Tang Xuanzong believed that punishment was a means to make people reform, rather than simply punishing criminals.

I. For you to kindly consider enlightening of the enthronement/coronation customs during the Han dynasty specifically. I have found details concerning this but they are mostly related to the Qing dynasty.

II. For you to kindly make a blog post about Emperor Ai' of Han.

I hope that you would be kind enough to consider my requests. Thank you so very much.