An Lushan Rebellion 1: 安史之乱 Empire Fall

→ Music: ← Beyond the River

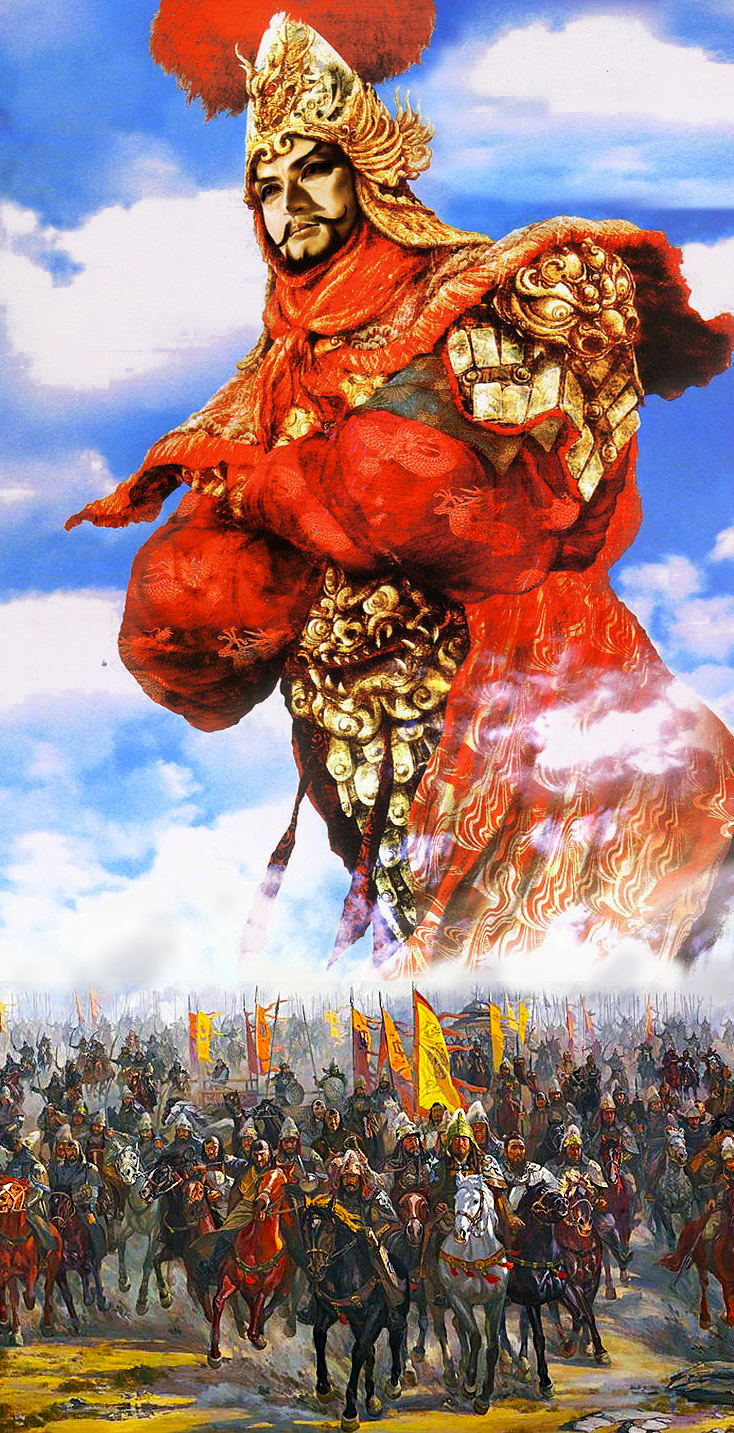

The three of them burned it all down. A foreigner who became the most powerful general in the realm, a fatal beauty who corrupted the Emperor's good senses, and the beloved Emperor whose sins incurred the wrath of Heaven. That's what a layman who lived in 8th century China would have told you about the burning, dying world around them. Its all they could say to give explanation to the universal hellscape around them in what we would call the An Lushan Rebellion- a calamity that some academics have to have point out to have killed 2/3 of the Empire, a shocking 36 million people in the 750s~ or, translated to fractions: 1/6 of the entire globe at that time. Though this lofty number have been repeatedly challenged, even the most conservative historians still would mark the death toll at around least around 13 million, still 1/5 of the empire, and 13% of the world's population~ a figure that was only eclipsed by the global genocide of the Mongol invasions and the 2nd World War.

If the very simplified, overtly moralizing characterization of the three figures above sounded like shallow caricatures- ghosts to be resurrected to be denounced in stern warnings and preserved in eternal memory as object lessons, the modern reader should realize that the An Lushan rebellion laid as a membrane between a dream and a nightmare. Considering that untold millions of people were suddenly cast out of their prosperous lives from splendor, tolerance, and prosperity, and within a mere decade saw most of their families dead, their realm torn apart, see themselves reduced to savages and never see a future where even their grandchildren could rise again, one could forgive them for the harshness of these vengeful patchwork of testimonies. It was all that these millions of nameless, suffering voices could throw back against the god-like figures of a bygone age~ those lofty, pride-filled men, those dissolute women who charmed high and broke all the rules- who caused all the horrors to happen, who died too early to suffer with the rest of them, who abandoned them all without guidance in centuries of torment. One rebellious general, at the head of a conspiracy of foreigners had toppled the greatest empire in the orient, and ended a century and half of a Golden Age.

The massive rebellion spanned the reigns of three Tang emperors before it was finally quashed, and involved a wide range of regional powers- for it continued long after the death of the rebellious general An Lushan himself until it collapsed into an anarchic Battle Royale of thousands of Tang loyalists vs thousands of anti-Tang separatists, especially in An Lushan's home base area around modern Hebei, where many ethnic Arabs, Uyghurs and Sogdians had lived and plied their trades. At the height of the extremely bloody affair, it was not uncommon to see titanic forces each boasting the size of 200,000 soldiers grinding against each other. (and in the case of the Tang loyalists over 700,000 soldiers.) Numbers that were so astronomical that they practically looked 20th century. And just like the mortal struggle between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the 20th century, a number of battles in the An Lushan Rebellion invoked scenes that paralleled the "Meat Grinders" of Rzhev and the starvation of Leningrad. For instance, in the Siege of the doomed fortress of Suiyang, the defending Tang soldiers committed massed cannibalism until they have eaten their dead and nearly devoured all of the city's doomed citizenry.

The traumatic mental image left from the description above was but one fragment of the total (and mostly lost) mosaic canvas of misery and dehumanization, and but one of many clues that gave dimension to the total devastation upon the empire. For a stable empire that had only recently been in abundance, enlightenment, and splendor, this decade of strife would see the nightmares not unlike that of the Thirty Years War, WWI and Nazi Germany's invasion of Russia visited upon its people. In the end, though the Tang did eventually managed to survive the attack of this metaphorical gripping beast in a corporeal manner, one could argue that just like the tormented citizendry who barely survived the decade of destruction, only a shell or a shadow remained. Upon the conclusion of the affair the hobbling Tang dynasty was so utterly devastated, its internal affairs so ruined that it would never recover from this. In fact, China as a whole would not recover from this for nearly three centuries- long after the Tang's demise in 907. But worse than any damage that could be done to great metropolises, great libraries, and millions of its citizenry~ this rebellion also dealt to the Chinese soul another millennium long blow as well.

Where as the early Tang empire was greatly characterized by its liberal intellectual curiosity, multiculturalism, of acceptance of both foreigners and foreign ideas, the China that survived the devastation was forever poisoned to become a conservative, isolationist, and xenophobic society deeply characterized by a general mistrust of foreigners and foreign ideas and for a millennium afterwards (some, including myself would say all the way until the 21st century) to be scornful of the very virtues their liberal ancestors embraced.

So as to say. Even after, the bleeding empire had walked away from the beast that had griped it, had wrestled with it. A long abiding damage had been branded to its soul. All that was great about the Tang dynasty died in this conflagration.

THE CAREER GENERAL

A Sogdian (Afghani) Auxiliary Cavalryman in Tang service

Though we know the general today by his Sinicized name of An Lushan, the general's given name was anything but Chinese. In fact the general was half Turkic~ which in the 8th century actually would denote he was an Asiatic featured man hailing from the Mongolian steppes (the ancestral homeland of the Turks before they migrated westward and adopted Islam) his other half was Sogdian (the ancient region of modern Afghanistan and Tajikistan.) This general would have looked like a modern Afghani but with certain noticeable Mongolian, or east Asian features. For the modern reader it is critical that we understand the peculiar interplay between a frontier foreigner such as An and the empire itself- especially the 8th century Tang dynasty's reliance on its frontier generals.

Tang dynasty pottery depicting a "foreigner" merchant with an exaggerated long nose and jutting beard and his son ontop of a Batrian camel. By the 750s the Tang would have had nearly 150 years of liberal commerce with the traders from as far as Damascus, Baghdad and Constantinople. Persian traders were frequently depicted in their historically accurate buckskin riding coats.

The family name An 安 was derived from the Chinese name for Bukhara in Sogdiana (present-day Uzbekistan). The given name Lushan is a sinicized form of the common Sogdian name ܪܘܚܫܐܢ Rowshān meaning "the Bright One," closely related to the Sogdian female name of Roxana. His name has also been transcribed as Āluòshān (阿犖山.) An Lushan’s ancestors belonged to a group of Sogdians expatriates, his father was a Sogdian merchant employed by the then flourishing Eastern Göktürk Khanate in modern Mongolia to administer the finances of its domains, his mother was from a local noble Ashide clan and served as a sorceress to the boy's tribe.

The boy's father died early, and his mother Lady Ashide soon married a Turkic general named An Yanyan (安延偃). An Lushan therefore took the name of An per custom to honor his adopted father. Early in the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang around 713–741 A.D, there was a great disturbance among the Göktürk tribe that An Yanyan belonged to most- likely a civil war as a result of succession disputes. As a result An Lushan and his extended family fled the Turkic domains and entered the Tang as refugees. Since the Eastern Göktürk Empire had long served as a Tang vassal- therefore have often sent the Tang its own auxiliaries, it was not difficult for An, his cousin An Sishun, and other soldiers of non-Chinese origin to find avenues to enlist in the one million Tang military as young recruits.

Faces of Buddhas unearthed from the great copper monastery/fortress of Mes Aynak in modern Afghanistan, alongside the natives of modern Afghanistan. DNA evidence has concluded that despite the ceaseless migrations across the Silk Road, most of the natives of the region still possessed nearly identical DNAs as the skeletons unearthed from 2000 years ago. It should be noted that powerful "Asiatic" hordes~ the likes of the Huns, White Huns, Saramatians, and the Göktürks would have regularly intermarried with the Persian- Sogdian natives. It was a world where people with flaming red beard (at the center) and an east Asian looking man (at the bottom right) simultaneously inhabited.

In the middle of the 8th century, the many oasis Kingdoms along Tang's western frontiers imploded in a series of violent overthrows and massive revolts. This would set the stage for a series of Tang interventions in the region to acquire the many Kingdoms as Tang vassals.

→ Music: ← On the Battlefield

Though the eponymous general was introduced as the villain of the story, a traitor who betrayed his Emperor and served as the linchpin of dooming millions to slaughter and centuries of suffering, it should be pointed out that An had began as a martial hero. In fact, for nearly three decades An had been a defender and one of the greatest savior of the empire on multiple occasions. One motto to keep in mind for general An Lushan as he rose through the ranks should be the haunting line from the movie Dark Knight, "You either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain." After all- who else could so utterly tear apart the empire's defenses with ease and exploit its fatal flaws if not for one of its fiercest and most consumate defenders?

For those who are curious how can a mere enlisted auxiliary could be so rapidly promoted to the position equivalent to a field Marshal or Generalissimo in modern military within only two and a half decades. The quick answer is that the organization of the Tang army in the middle of the 8th century bears a striking similarity to the "barbarian" dominated Roman Army of the 400s.

Just like the latter Roman Empire's neglectful and over-privileged native aristocracy, the aristocracy of the Tang in 8th century would have be similarly...vestigial. In previous centuries, the ranks of Tang nobles had composed largely of loyal warrior vassals who sent their sons to become officers and palace guards to prove their devotion and was in turn promoted to great positions based on battle merits. In the succeeding century, however- usurpers such as Empress Wu and the feeble Zhongzong Emperor had feared opposition from these entrenched "old guards" in turn sold high imperial appointments to lackies solely devoted to them in order to foster a pool of loyal sycophants. By the beginning of the 710s, the entire court was largely composed of stooges who simply purchased their offices through bribes and was kept because they were favored.

A consequence of these policies was that the quality of the officer corp and a patriotic native caste was thoroughly diluted. Once, prestige rested on struggles that united the fortune oneself with the state itself. Now, the avenue to power could be much easily attained by courtiers and bureaucrats who shunned hardship on the saddles and in the harsh frontiers. The deprivation of a reliable pool of native officers essentially forced the Tang emperors to place the burden of securing and policing the vast empire on those eager non- natives who would, or are still willing to toil as professional soldiers.

The Tang Dynasty in the 740s with the majority of its military deployments marked with "帥"~. The vassal state of Uyghur Khaghanate is marked in light yellow. Aside from the northeastern Tang garrison along the Khitan boarder (which would eventually be helmed by An Lushan) the majority of the dynasty's attention was turned to the southwest, to contain both the resurgent Tibetan Empire and the small Kingdom of Nanzhao. By this point these boarder generals and military governors would have been so powerful their frontier garrison practically acted like their own little kingdoms.

And just like the Various 5th century Germanic (or Gothic) generals like Stilicho, Arbogast and Ricimer who rose to become bulwarks of the Roman Empire, and in turn promoted to become palace guards, military governors, and marshals- for the Tang, a similar pattern caste of born officers emerged. Various Turkic peoples, Qiang (a Burmese- Tibetan people) and Koreans soon became the new generation of generals for the Tang with each frequently assigned with well over 80,000 per front.

And for over 60 years under the wise Xuanzhong Emperor, this system of generalship by meritocratic contracts worked remarkably well for the empire. The truth of the matter was that it was not that the likes of An Lushan needed the empire, but rather it was the empire that desperately needed exactly the kind of man like An to police its frontiers. For from the 730s-750s, a storm of chaos and anarchy swept across the frontiers of the empire.

EMBERS ON THE FRONTIERS (740s-760s)

The North Crumbles

Beginning in 742, Eurasia entered a 13-year period of savage political turmoil. In that year the Türkic dynasty of the eastern Eurasian Steppe was overthrown and then replaced by Sogdian-influenced Uighur rulers. As a result of this turbulent change of leadership, the entire northern front of the Tang was lit up in a series of massive revolts and revolutions. For An Lushan- it must have been an echo of his childhood when he was forced to flee into Tang territory.And for over 60 years under the wise Xuanzhong Emperor, this system of generalship by meritocratic contracts worked remarkably well for the empire. The truth of the matter was that it was not that the likes of An Lushan needed the empire, but rather it was the empire that desperately needed exactly the kind of man like An to police its frontiers. For from the 730s-750s, a storm of chaos and anarchy swept across the frontiers of the empire.

EMBERS ON THE FRONTIERS (740s-760s)

The North Crumbles

Over night, hundreds of local towns simultaneously ejected their Türkic overlords and to the shock of the casual observers, it appeared that these concerted "revolution" was orchestrated and instigated by the castes of Persian/ Sogdian merchants and tradespeople. Rumors described it almost as a conspiracy of caravansaries (trading post fortresses.) The way that these merchants could acting in concert like a consortium of trade guilds to play Kingmaker aroused a good degree of alarm from the Tang regime, but since the affair was relegated largely outside of the Tang boarders, it was soon dismissed.

However, it did serve as the first of a series of dominos that would lead to the calamity ahead- and it would do well for the readers to remember these rumors along the ancient Silk Road grapevine describing the supposed tangle of conspiracy orchestrated by Persian and Sogdian merchants. Refugees and emigrates soon streamed into Tang domains, though the Tang was still well able to take care of the trickle of refugee that hemorrhaged monthly into its boarders, it did serve to add pressure to the stability of the northern front.

Umayyad Caliphate and surrounding regions in 743 CE, Abbasids, one of their vassals would revolt three years later from their base in Merv, beside the Caspian Sea- and incidentally adjacent to the Tang's western-most vassals (Maked in gold.) The new dynasty traced its lineage to Al- Abbas, one of the uncles of the Prophet Mohammad. "X" marks the location of the Talas River where the Tang and the newly emerged Abbasids fought in 751.

The Defeat in the West

Amazingly, despite the great status of both of these 8th century superpowers, for both of the combatants, this battle- and the air of animosity between them was quickly forgotten.

The Tang Empire in 742, the small Kingdom of Nanzhao is marked in gray.

But the minor embarrassment of 8,000 casualties on the Talas River was nothing compared to the sheer ineptitude for the Tang to crush the small Kingdom of Nanzhao to the Tang's south. The fact that such an insignificant minor power could repeatedly repel tens of thousands of Tang soldiers meant they were in need with a new type of general. The only bright spot for Tang military was their limited success in pinning down the dynasty's archnemisis, the resurgent Tibetan Empire under the expansionist Tibetan Emperor Trisong Detsen. And here is where An Lushan came in, to score a series of resounding victories when the empire sorely needed them.

→ Music: ← Ten Thousand Arrows

ENTER AN LUSHAN (736-743)

To pick up the story where we left off of the great general, we should rewind the time frame a decade earlier before Talas and Nanzhao, to the year 736. Keep in mind that as the general racks up his promotions, in the other corners of the Tang frontiers, nearly all of other Tang generals were rebuffed and repelled by either the Abbasids or the Kingdom of Nanzhao. Whereas all the other generals met their aforementioned looses, An simply kept on winning.

An Lushan’s military career took place on Tang China’s northeastern frontier in what is now Liaoning province. The unstable region~ inhabited by a war-like nomadic tribal confederation called the Khitans has been a constant thorn at the Tang court's side and for hundreds of years raided deep into Chinese territory. Worse yet, these savvy conquers had a terrible (and from their perspective: hilarious) habit of suddenly always showing up to fight for traitorous Tang generals and rebellious Tang Princes. In fact, they had been doing this for so many centuries- even against Tang predecessors it is generally expected that whenever there was a rebellion the Khitans would show up to plunder and rape the Tang frontiers then retreat back into their frigid northern heartlands.

The first record of An Lushan's name in the Tang annals was the year 736, when- serving under General Zhang Shougui as a scout officer of the Pinglu Army (平盧軍) An disobeyed Zhang's orders and made an overly aggressive attack against the Khitan and the Xi tribesmen there, and was resoundingly defeated. In the aftermath of this debacle, nearly all of his superiors advocated for him to be executed as an example for the army. But fortunately for An, he was pardoned by none other than the Xuanzong Emperor himself- who suggested leniency. A year after the debacle, An Lushan rebounded with a series of spectacular victories and captured the heartland of the region and rose rapidly in rank, receiving his first independent command in 742. For these series of achievements, An was made a full fledged general by the age of 33.

ICE TO ICE

Aside from employing conventional massed cavalry tactics, An also devices an especially insidious method to whole hardheartedly paralyze his foes. An frequently left large caches of alcohol as trap for his foes and would wait for the enemy tribesmen to discover the jugs and drink themselves all to a stupor. An would then rush in to attack the enemy camps at night or pre-dawn, when the defenders were all still succumbed to the effects of the drink and slay all of the defenders (the alcohol were most likely drugged to prolong the stupor.)

ICE TO ICE

Aside from employing conventional massed cavalry tactics, An also devices an especially insidious method to whole hardheartedly paralyze his foes. An frequently left large caches of alcohol as trap for his foes and would wait for the enemy tribesmen to discover the jugs and drink themselves all to a stupor. An would then rush in to attack the enemy camps at night or pre-dawn, when the defenders were all still succumbed to the effects of the drink and slay all of the defenders (the alcohol were most likely drugged to prolong the stupor.)

An Lushan made massive forays into the frigid Khitan homelands. Through combining a well drilled Tang army at his back and savvy understanding of tribal politics (remember, An himself is of nomadic descent) An was able to brutally exploit the organizational weaknesses of the tribesman and in over 20 years be made into one of the empire's most powerful marshals. In essence, he would have became the emperor's own "fireman" relied on to put out the fire of all the imperial foes.

For the modern reader, it must have been both comical as well as hard to imagine whole tribes of seemingly cartoonishly naive- scarred and battle hardened warriors be so simply disarmed and slaughtered, not only once, but repeatedly fall to this kind of cheap ploy. But if one were to consider that how "sedentary" of a lifestyle the mere brewing of alcohol required~ the fact that distilling of liquor required the cultivation sorghum or a hops grove, constant monitoring. And a several facilities to manufacturing them in large quantities, meant that for nomadic cultures who are constantly on the move, only saddled with the lite Kumis (fermented milk,) true painkilling- worry-killing liquor was a rare luxury, obtained- if they were lucky through trading and raiding. It wouldn't be hard to imagine An purposely "stage" a caravan that just happened to be filled with all sorts of expenses and peppered with much alcohol. This tactic proved so successful that An was able to continually destroy whole hordes of hundreds of enemies with these- poison + raid attacks.

An would always try to strategically assassinate important (and often the most hostile) clan members of his enemies tribe in order to foster a crisis to paralyze the leadership. In conjunction with his ability to rip his foes apart, whenever he crushed a tribe, he also made sure to take many hostages from the tribe's ruling clan to guarantee good behavior. But he would also make them into his loyal vanguards, An selected some 8,000 soldiers among the surrendered Khitan, Xi, and Tongluo (同羅) tribesmen, organizing them into an elite corps known as the Yeluohe (曵落河), which meant "River Breaking Braves."

THE HAMMER OF THE KHITANS (743)

743, 7 years since his first recorded battle, An had drove deep and repelled most of the Khitan tribesmen who inhabited in the region. Often securing alliances with some local chieftans while savagely turning his forces on the "disobedient" ones who resisted him. And in time he had not only proved himself to be an extremely efficient commander~ but also an extremely dishonorable one as well.

→ Music: ← Metropolis

However impressive An's generalship skill was- without the general's own brand of political savvy, he would have never made as far as he eventually achieved. Where he distinguished himself well above the other generals (most of the other generals possessed ancient lineage of illustrious Turkic Princes who traced their glory alongside the founding of the Tang dynasty itself) The other half of An Lushan's path to power lays entirely in his particular brand of "barbarian charm."

With his successful campaigns as a ticket to be slowly introduced to various members of the imperial court, An was eventually presented to the great Xuanzong emperor himself. What happened next was solely due to An Lushan's extraordinary ability to ingratiate himself to the aged emperor. It was here we see how he was able to secure not only a stable position beside the monarch but be provided with endless opportunities for future advancements. And it is also here that we discuss the second key figure of our great cataclysm, the beloved Xuanzong emperor.

The Tang imperial capital of Chang' An was a metropolis in the 8th century, boasting well over 1 million of the empire's 70 million populace, the secondary capital of Louyang would also boast around 1 million citizens. Tang China's population before the An Lushan rebellion would equal to 1/4 of the world's 228 million- 280 million total population.

The Self Made Emperor

Astute, tireless, and decisive, the once young Prince Longji came from a very minor branch of the Tang imperial line of succession, because of his painful childhood where his mother was slain by his paranoid grandmother- the notorious Empress Wu, he actively took up the leadership of his father's household- often dragging, often leading his shy and inept father to political victories over the other branches of the imperial clan until his father- then him respectively became Emperors.

The empire that this dynamic Emperor would manage would be nothing less than his wise and forward- looking personality. When he ascended the throne after the abdication of his father, the Tang was teetering, its ministry was bloated with corrupt and inept sycophants, and the empire had suffered a series of defeats against the rival Tibetan Empire. To all within the empire it was as if the empire has already entered into an irreversible period of terminal decline.

But Li Longji- the now Xuanzong Emperor saved the day. By appointing able ministers and diligently ruling his empire, he restructured the entire empire's bureaucracy, clamped down on corruption, kicked out the useless officials, lowered taxes while at the same time dealt several fatal blows to its enemies on the frontier. And to the astonishment of both the Tang's citizens as well as its many neighboring kingdoms. The waning Tang instead soared into a golden age and reached its zenith of prosperity and influence.

By the time An Lushan- merely a somewhat successful foreigner general from the frontiers formally paid his homage to Xuanzong Emperor in 743, the 58 year old Emperor would have already ruled the empire for 31 prosperous years. Upon their first official meeting An thanked the Emperor for personally pardoned him half a decade ago- and respectively Emperor Xuanzong treated him well and allowed him to visit the palace at all times.

Also- it would seem the by now morbidly obese general had developed a special rapport with Xuanzong. One can say that An was well aware of certain comical stereotypes the Chinese have always regarded foreigners and would repeatedly...degrade himself by ingratiating himself as some sort of Falstaff- like comical buffoon. At 743, he was so fat that his full belly was as thick as the waist of two men, and Xuanzong, on one occasion, jokingly asked him, "What does this barbaric belly contain?" An promptly responded in a dumbfounded manner with a simpleton's confused stare "Other than a faithful heart, there is nothing else." This humored the Emperor greatly.

"BARBARIAN CHARMS"

For the matter he found himself entangled with was very much intertwined with the Emperor's deepest wishes. And here is where we are introduced to our third character of the great calamity; one of the most legendary beauties in all of Chinese history and another key figures that would trigger the rebellion that would burn the empire down.

In 737, 6 years before An's meeting with the Emperor. Xuanzong Emperor's then- favorite Concubines, Concubine Wu died. Xuanzong, struck with immense grief would not come to any of his harem women, which at the time numbered in the thousands. Instead, the solitary minded Xuanzong retreated to 华清池 the Huaqing Pool Palace- his geothermal hot spring resorts outside the imperial capital beneath the green mountains of Mount Li. It was there- at the Huaqing Pools that an eunuch introduced him to a young beauty that frequented the bath. According to court gossip, the eunuch witnessed the full fleshed beauty ascending nude from the translucent pink jade rimmed pool.

Xuanzong was immediately infatuated with the great beauty though he was in his early 50s and she only 18, and she quickly became infatuated (or at least greatly sought to attach herself) with him as well. It was here that their blossoming infatuation turned not only to strangeness, but also to bizarre dimensions as well. For the young beauty was already married, and she was married to none other than Li Mao, one of Xuanzong's own 30 sons. To be precise, Li Mao was Xuanzong's 18th son, someone whose existence he was so outside of Xuanzong's existence that he must likely had never met the girl in person as a "Princess" considering that Princesses and Imperial concubines of his children would nave numbered in the hundreds. Despite this technical detail, the two were both very well aware of the great impact of damage that could be done to them both if they were to initiate their tabooed affair.

In order to pave the way for their affair to proceed, the two of them would have to clear the way both legally as well as politically. Xuanzong first approached his son about the matter and Li Mao- who had always been a submissive insignificant member of the household did not object at all to the matter, and quickly divorced Yang. Then~ in order to spiritually "restart" her previously attached status, and make her a "new" woman, Xuanzong stealthily arranged for Yang to become a Daoist nun with the tonsured name Taizhen (太真) in order to prevent any criticisms- since- by entering into the priestess-hood required unattaching- disassociating herself from her past life, from relinquishing her possessions, status, and property she was "cleansed" of her past life and given a fresh slate. With this technicality, this newly cleansed woman would be free to start her life anew.

Yang then stayed, for a brief while, as a Daoist nun in the palace itself, before Xuanzong made her an imperial consort after bestowing his son Li Mao a new wife from a respected family and seeing the new couple married off. Yang henceforth became the favorite consort of the emperor like Consort Wu before and was given the endearing moniker of Yang "Guifei" 杨贵妃 meaning the "Precious Consort" Yang. From all records it seemed the two really enjoyed each other's company, and from that day on, Xuanzong would have no other woman but her.

Lady Yang was so adored that when she missed favorite fruit~ lychees, 荔枝 which were only grown in her homeland in southern China, Xuanzong established an empire wide version of the Pony Express where hundreds of riders would take shifts day and night in a breakneck cycle to transport lychees at the peak of their freshness into the palace solely for her enjoyment. It was an extravagant gesture of devotion not unlike that of Shah Jahan...or befitting that of a Marie Antoinette.

Now with the three of our story's main characters established, we should examine how the interplay of the three would lead to the conflagration that would set the empire in flames.

By the time An Lushan visited Xuanzong's court 743, the Emperor was restored to his happiness and always had the great beauty around him. On the surface, for the last 6 years since 737 all treated her as his new Empress, and bowed to her as if she was the most powerful woman in land. But underneath the surface, the complications of the entire affair was lost on no one. The Tang- for their part were extremely liberal in terms of their sexual politics even by 20th century standards. But for all those who were told of the nature of the Emperor's new union, it was not say...uncommon for there to be plenty of stunned extra blinks.

And it was this gnawing tension that stemmed from gossip and whispers that weighed somewhat on Xuanzong and Consort Yang both. And it was the ignorant barbarian who came to their rescue. For in 743 it became immediately apparant to An, that the way to even greater favor beside the emperor lies in ingratiating himself to the one and only Precious Consort Yang.

Once, as An was allowed to freely enter the palace, he was reported by the ministers to have asked that he become an adoptive son of Consort Yang Guifei, and Emperor Xuanzong- who couldn't resist laughing, agreed. Thereafter, after this little farce, before seeing the Emperor again, he bowed to Consort Yang first before bowing to Emperor Xuanzong, and stated, "Barbarians bow to mothers first before fathers." Consort Yang was greatly amused, and began to call him, "my son." Xuanzong, now believing An was as submissive to him as an adopted son to a father, or a harmless pet, showed him even greater favors, and from that moment on, even began to call him, "dear son," along with Consort Yang.

It was at this moment, that one must wonder what the old general was truly thinking. This very same general who knew six non-Chinese languages before he even reached the age of twenty, was able to fluidly conjugate foreign and Chinese and draft edicts with perfect ease, who served as an interpreter in the army and later would become a general before he was even 33- all the while could barely even awkwardly pronounce common Chinese word in front of the laughing Emperor. The same man who- this very same year exterminated the large portion of several Khitan tribes. No- if we judge An by what he would do next years, he would definitely seemed not to inhabit the same person as the Uncle Tom clown laughing before his self proclaimed betters.

A GATHERING OF SHADOWS (744-747)

In 744, An, by now a royal favorite was- upon Consort Yang's suggestion, made the military governor (节度使) of three frontier Provinces—Pinglu, Fanyang and Hedong (modern Hebei), the warden (jiedushi) of whole of Manchuria. In effect, An was given control over the entire area north of the lower reaches of the Yellow River, including garrisons about 164,000 strong, of 40 percent of the Tang forces.

He was continually supported not only by Xuanzong and Consort Yang, but also most critically by the High Chancellor Li lin-fu, who favored foreign generals because he feared that native Chinese generals might usurp his authority at court.

And it would seem the two men~ An and Chancellor Li quickly formed a symbiotic patron- client relationship. Through this arrangement, An was essentially permitted to devastate the north however he wished. Li would provide all sorts of political and legal protection for An while An was unleashed to make the northmen howl.

Wanting to show his military abilities, An often attempted to provoke a full on fight with the northerners and frequently resorted pillaged the Khitan and the Xi people, and he was blamed by later conservative historians such as Sima Guang for instigating the great Khitan and Xi rebellion in 745, which An promptly crushed, again he looked like a hero and was promoted.

According to the Song Dynasty historian Sima Guang, it was said that at this point, An was already attempting to increase his own strength and planning a rebellion, and in 747, he claimed to be supposedly building a massive fortress called Fort Xiongwu (雄武城) and asked the neighboring military governor Wang Zhongsi to contribute troops, hoping to hold onto the troops that Wang would send and not return them. Wang, instead, led the troops himself to Xiongwu in advance of the rendezvous date and, after participating in the building project, returned with the soldiers, and submitted reports to Emperor Xuanzong that he believed An was planning treason. Li Linfu, who was at this point apprehensive of Wang as a potential rival, used this as one of the reasons to indict Wang, and Wang was, later in 747, removed from his post.

GENERALISSIMO OF THE REALM & PARTNER OF MY LABORS (748-751)

As we have mentioned earlier, chaos swept across the steppe in 742 all along the Tang's northern frontier for the next 13 years. As a series of Turkic overlords were overthrown and their clients rebelled in a series of wars and refugee floodings upon the backs of northern China. And as the fires of chaos erupted all along this frontier, An actually made good use of the deteriorating situation and intervened in the region on behalf of the Tang, gaining several boarder cities, pastures and land concessions. It should be mentioned that he also took opportunities to conscript many of these new refugees as not only his own private soldiers, but also his personal clients. Though they technically pledged their Loyal in name to the Tang dynasty, ultimately they owed everything to him.

In 748, Emperor Xuanzong awarded An Lushan an iron certificate promising that he would not be executed, except for treason, and in 750, he created An Prince of Dongping, setting a precedent for generals not of the imperial Li clan to be created princes.

In 751, following An's escalating series of decisive victories, An was personally invited by the Xuanzong Emperor back to the Capital and presented with a massive palace designed and outfitted just specially for him that befitted a royal Prince of the blood. The favor of the Emperor was such that the luxury palace was furnished with court luxuries such as gold and silver furniture, the livery worthy of a nobleman of the highest order, and a pair of ten-foot-long by six-foot-wide couches appliqued with rare and expensive sandalwood and gild threaded silk. Alongside these impressive possessions were also a staff of court musicians and troupes of dancing girls.

On An's birthday, 20 February 751, Emperor Xuanzong and Consort Yang awarded him with clothing, treasures, and a week of elaborate banquets. On 23 February, when An was summoned to the palace, Consort Yang, in order to please Emperor Xuanzong, had an extra-large infant wrapping made (it should be mentioned that these large white bandages looked like a giant diaper) and wrapped An in it, causing much explosion of laughter among the ladies-in-waiting and eunuchs.

By this point An Lushan was not only the Generalissimo, warden of the north, but also the most powerful military figure in the entire empire with direct command of over 164,000 troops, and the fact that the 48 year old was running around in a giant white diaper while making a racist fool of himself in front of a laughing harem was one of the strangest moment in all of Chinese history.

When Emperor Xuanzong asked what was going on, Consort Yang's attendants joked that Consort Yang gave birth three days ago and was washing her baby Lushan. Emperor Xuanzong was pleased by the comical situation and rewarded both Consort Yang and An greatly. Thereafter, whenever An visited the capital, he was allowed free admittance to the palace, and there were rumors that he and Consort Yang had an affair. But Xuanzong, in his usual humor, did not took heed to the rumor.

TURN (751)

Despite these great rewards, by late 751 An was very worried. And if we were to look at An's world from his perspective, he had every reason to be. For his long time protector and patron- the Chancellor Li was quickly loosing his paramount status at court, his health was also swiftly deteriorating. An's stairway to power, his primary pillar his at court would be soon under leash of strangers. Without Li~ An was just one of the many expendable chess pieces on the board.

But the worst news of all was the fact that the man who would replace the aging Chancellor Li was not only someone who completely loathed him, but also someone who he in turn utterly could not touch. The new Chancellor was none other than the cousin of the beloved Consort Yang: Lord Yang GuoZong 杨国忠. It was the rivalry between these two men that would tear the empire apart.

It was this initial suspicion that greatly alarmed him, and as his spies collected the records of a series of suspicious activities from Chancellor Li's old files~ such as An's attempt to loan troops indefinitely to build the "Fort Xiongwu (雄武城)" from his neighboring governors, the massive blindspot through out Li's career that permitted An to act as he wished in the region, and- most critically, An's many, many clients and vassals that only answered to him.

For as Yang observed, in late 751, An launched a major attack against the remaining Khitans who opposed him, advancing quickly to the heart of Khitan territory, but, hampered by rains, was defeated by the Khitan. An himself was almost killed, and, after retreating, blamed the defeat on two of the imperial generals Ge Jie (哥解) and Yu Chengxian (魚承仙), Yang had placed to monitor An- executing them. In 752, An quested thousands of soldiers to launch a counterattack against the Khitans.

There is a great level of credence to the 2nd theory, for by the time Chancellor Li finally died in 753 and Yang formally took over all aspect of the Chancellery, Li was posthumously dishonored and his family members were exiled. An never feared the new Chancellor the same way he feared Li and the two frequently got into heated arguments in court.

Yang Guozhong made repeated accusation against An to Emperor Xuanzong that he was plotting a rebellion, but the accusation were dismissed by Emperor Xuanzong. In spring 754, Yang asserted, to the Emperor, that An was set on rebelling, an accusation Yang had made before. Yang predicted that if Emperor Xuanzong summoned An to Chang'an, he would surely not come. However, when Emperor Xuanzong tested Yang's hypothesis by summoning An, he immediately showed up in Chang'an and claimed that Yang was making false accusations.

Thereafter, Emperor Xuanzong refused to believe any suggestions that An was plotting rebellion,

FIRE (752-755)

In the spring of 755, matters were beginning to come to a head. When An Lushan submitted a petition to have 32 ethnically non-Han generals under him replace Han generals, this was accepted by Emperor Xuanzong, despite opposition from Yang Guozhong and his fellow chancellor Wei Jiansu who took An's use of non-Han generals as a sign of impending rebellion.

By now, exhausted of ways to prove of An's motives, Yang and Wei then suggested a soft approach and proposed that An be promoted to be Chancellor- though only in a ceremonial role and far- far away from An's base of power on the northeastern frontier, and in his absence that his three province garrisons be divided between his three deputies. An never gave an official response to this "promotion" in fact- it was silence, long gnawing silence that came from his frontier.

ZERO HOUR (755)

An Lushan had used the pretext of claiming he had received "a secret edict" from Emperor Xuanzong to advance on Chang'an to remove Yang. It was at that moment- where 40% of the empire's best and most experienced troops barreled down toward the capital with nothing at all to stop them that Xuanzong and the entirety of the Tang court realized that for the last 12 years they had underestimated a consumate predator whose entire career consisted of deceiving his foes and leaving wakes- no whole fields of corpses.

Tang dynasty Lokapala; or tomb guardian figurine that usually depicts the Four Heavenly Kings- This particular one, depicts the Western Heavenly King Virūpākṣa or in Chinese: "Guăng Mù Tiānwáng" (广目天王.) Usually the "western" King is usually depicted with exaggerated Indo-European features, such as a ferocious bearded aspect, fat cheeks, as well as well as an exaggerated nose. During the Tang dynasty- most of these figurines depicts contemporary Sogdians and Persians encased in Tang armor.

On another occasion, when Emperor Xuanzong's son Li Heng the Crown Prince was in audience, he refused to bow to Li Heng, stating, "I am a barbarian, and I do not understand formal ceremony. What Sire is a...Crown Prince exactly?" Emperor Xuanzong responded, "He is the reserve emperor. After my death, he will be your emperor." An apologized, stating, "I am foolish. I had only known about Your Imperial Majesty, and not that there is such a thing as a reserve emperor." But he promptly bowed following suit for decorum's sake, but Xuanzong, believing him to be honest, favored him even more.

It was these...little dosages of feigned ignorant- but sincerity displaying remarks that slowly made him a figure well remembered and well amused by the emperor,. But as we shall see, it was what An does next that cemented his station as part of the Emperor's inner circle.

华清池 the Huaqing Pool, Consort Yang ascending from her bath

THE BEAUTY

Xuanzong was immediately infatuated with the great beauty though he was in his early 50s and she only 18, and she quickly became infatuated (or at least greatly sought to attach herself) with him as well. It was here that their blossoming infatuation turned not only to strangeness, but also to bizarre dimensions as well. For the young beauty was already married, and she was married to none other than Li Mao, one of Xuanzong's own 30 sons. To be precise, Li Mao was Xuanzong's 18th son, someone whose existence he was so outside of Xuanzong's existence that he must likely had never met the girl in person as a "Princess" considering that Princesses and Imperial concubines of his children would nave numbered in the hundreds. Despite this technical detail, the two were both very well aware of the great impact of damage that could be done to them both if they were to initiate their tabooed affair.

Lady Yang was so adored that when she missed favorite fruit~ lychees, 荔枝 which were only grown in her homeland in southern China, Xuanzong established an empire wide version of the Pony Express where hundreds of riders would take shifts day and night in a breakneck cycle to transport lychees at the peak of their freshness into the palace solely for her enjoyment. It was an extravagant gesture of devotion not unlike that of Shah Jahan...or befitting that of a Marie Antoinette.

Consort Yang became so favored that whenever she rode a horse, the eunuch Gao Lishi would attend her. 700 laborers were conscripted to sew fabrics for her. Officials and generals flattered her by offering her exquisite tributes

TENSIONS (743)Now with the three of our story's main characters established, we should examine how the interplay of the three would lead to the conflagration that would set the empire in flames.

And it was this gnawing tension that stemmed from gossip and whispers that weighed somewhat on Xuanzong and Consort Yang both. And it was the ignorant barbarian who came to their rescue. For in 743 it became immediately apparant to An, that the way to even greater favor beside the emperor lies in ingratiating himself to the one and only Precious Consort Yang.

Top: Anachronistic portrait of An Lushan, by the late 740s and early 750s he would have been not only morbidly obese but also covered with so many skin ulcers that he would be frequently drove into such a foul mooded frenzy that he would whip and cane his servants for the smallest disturbances. As the decades progressed he also became increasingly blind. He would- of course never show this side of his personality when he appeared before the Xuanzong Emperor or Consort Yang.

Once, as An was allowed to freely enter the palace, he was reported by the ministers to have asked that he become an adoptive son of Consort Yang Guifei, and Emperor Xuanzong- who couldn't resist laughing, agreed. Thereafter, after this little farce, before seeing the Emperor again, he bowed to Consort Yang first before bowing to Emperor Xuanzong, and stated, "Barbarians bow to mothers first before fathers." Consort Yang was greatly amused, and began to call him, "my son." Xuanzong, now believing An was as submissive to him as an adopted son to a father, or a harmless pet, showed him even greater favors, and from that moment on, even began to call him, "dear son," along with Consort Yang.

It was at this moment, that one must wonder what the old general was truly thinking. This very same general who knew six non-Chinese languages before he even reached the age of twenty, was able to fluidly conjugate foreign and Chinese and draft edicts with perfect ease, who served as an interpreter in the army and later would become a general before he was even 33- all the while could barely even awkwardly pronounce common Chinese word in front of the laughing Emperor. The same man who- this very same year exterminated the large portion of several Khitan tribes. No- if we judge An by what he would do next years, he would definitely seemed not to inhabit the same person as the Uncle Tom clown laughing before his self proclaimed betters.

A GATHERING OF SHADOWS (744-747)

In 744, An, by now a royal favorite was- upon Consort Yang's suggestion, made the military governor (节度使) of three frontier Provinces—Pinglu, Fanyang and Hedong (modern Hebei), the warden (jiedushi) of whole of Manchuria. In effect, An was given control over the entire area north of the lower reaches of the Yellow River, including garrisons about 164,000 strong, of 40 percent of the Tang forces.

He was continually supported not only by Xuanzong and Consort Yang, but also most critically by the High Chancellor Li lin-fu, who favored foreign generals because he feared that native Chinese generals might usurp his authority at court.

And it would seem the two men~ An and Chancellor Li quickly formed a symbiotic patron- client relationship. Through this arrangement, An was essentially permitted to devastate the north however he wished. Li would provide all sorts of political and legal protection for An while An was unleashed to make the northmen howl.

According to the Song Dynasty historian Sima Guang, it was said that at this point, An was already attempting to increase his own strength and planning a rebellion, and in 747, he claimed to be supposedly building a massive fortress called Fort Xiongwu (雄武城) and asked the neighboring military governor Wang Zhongsi to contribute troops, hoping to hold onto the troops that Wang would send and not return them. Wang, instead, led the troops himself to Xiongwu in advance of the rendezvous date and, after participating in the building project, returned with the soldiers, and submitted reports to Emperor Xuanzong that he believed An was planning treason. Li Linfu, who was at this point apprehensive of Wang as a potential rival, used this as one of the reasons to indict Wang, and Wang was, later in 747, removed from his post.

As we have mentioned earlier, chaos swept across the steppe in 742 all along the Tang's northern frontier for the next 13 years. As a series of Turkic overlords were overthrown and their clients rebelled in a series of wars and refugee floodings upon the backs of northern China. And as the fires of chaos erupted all along this frontier, An actually made good use of the deteriorating situation and intervened in the region on behalf of the Tang, gaining several boarder cities, pastures and land concessions. It should be mentioned that he also took opportunities to conscript many of these new refugees as not only his own private soldiers, but also his personal clients. Though they technically pledged their Loyal in name to the Tang dynasty, ultimately they owed everything to him.

An Lushan made massive forays into the frigid Khitan homelands. Through combining a well drilled Tang army at his back and savvy understanding of tribal politics (remember, An himself is of nomadic descent) An was able to brutally exploit the organizational weaknesses of the tribesman and in nearly 20 years be made into one of the empire's most powerful marshals. In essence, he would have became the emperor's own "fireman" relied on stomping out all of the imperial foes.

Later in 750, he tricked the Khitan and Xi chieftains into feasting with him, and then poisoned them. He then attacked the leaderless tribes, cutting the hordes into fragments and then continued on to slaughter the Khitans deep beyond their homeland until all of the chieftains in what constituted as modern Manchuria surrendered. It should be pointed out only months after his victory in 751 - on the opposite side of the Tang empire, a 100,000 strong Tang expeditionary force was defeated by the Abbasids at the Battle of Talas River. In the west there also came the report of failure to invade Nanzhao. While other fronts slowly receded, the northeastern front- for the first time in centuries (since the Sui dynasty 200 years ago) was...pacified.

For the layman, it would have nothing less than when Julius Ceasar decisively crushed the Gauls. And just like the aforementioned Ceasar-comparison, for An's great victories, he was treated with an 8th century version of an imperial triumph. By this point, a friendship had developed between An Lushan and the Emperor. When An went to Chang'an later that year to pay homage to Emperor Xuanzong, he presented Emperor Xuanzong with 8,000 Xi captives.

→ Music: ← Tribute

In 751, following An's escalating series of decisive victories, An was personally invited by the Xuanzong Emperor back to the Capital and presented with a massive palace designed and outfitted just specially for him that befitted a royal Prince of the blood. The favor of the Emperor was such that the luxury palace was furnished with court luxuries such as gold and silver furniture, the livery worthy of a nobleman of the highest order, and a pair of ten-foot-long by six-foot-wide couches appliqued with rare and expensive sandalwood and gild threaded silk. Alongside these impressive possessions were also a staff of court musicians and troupes of dancing girls.

By this point An Lushan was not only the Generalissimo, warden of the north, but also the most powerful military figure in the entire empire with direct command of over 164,000 troops, and the fact that the 48 year old was running around in a giant white diaper while making a racist fool of himself in front of a laughing harem was one of the strangest moment in all of Chinese history.

When Emperor Xuanzong asked what was going on, Consort Yang's attendants joked that Consort Yang gave birth three days ago and was washing her baby Lushan. Emperor Xuanzong was pleased by the comical situation and rewarded both Consort Yang and An greatly. Thereafter, whenever An visited the capital, he was allowed free admittance to the palace, and there were rumors that he and Consort Yang had an affair. But Xuanzong, in his usual humor, did not took heed to the rumor.

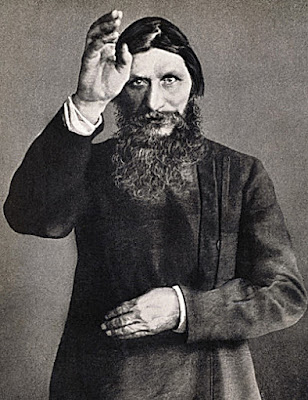

The 15th century Polish court jester Stanczyk, 18th century Swedish "court Negro" Gustav Badin, and Tsarist Court Mystic. All three men of lowly birth, but greatly favored by their autocratic rulers and given an extraordinary degree of freedom of expression to such a shocking degree that they practically talked down to their masters. Compared to these "Beverly Hillbillies" archetypes, An Lushan would fit right in with these oddballs of history.

TURN (751)

But the worst news of all was the fact that the man who would replace the aging Chancellor Li was not only someone who completely loathed him, but also someone who he in turn utterly could not touch. The new Chancellor was none other than the cousin of the beloved Consort Yang: Lord Yang GuoZong 杨国忠. It was the rivalry between these two men that would tear the empire apart.

Both contemporary chroniclers and later historians could not make out exactly what happened exactly happened between the two men, and as such there were plenty of theories in an effort to fill the vacuums in the greater narrative and explain what became a series of dominos that led to the great calamity. There were two main theories: one was that the young and brash Yang GuoZong was a corrupt upstart who was both arrogant and ruthless to all who he regarded to pose a threat to his clan.

THEORY ONE: A DUEL OF VIPERS

After all, by the 750s, the inner court surrounding the aging Emperor was bloated with Consort Yang's relatives- her several sisters and uncles were all given titles, and her brothers, and uncles were all appointed to key positions around the Emperor, and by the time of his appointment- Yang GuoZong, who was in his early 40s was indeed a notorious gambler and a wastrel, but keen with the political scene to maintain Xuanzong's favor.

In 752, as Chancellor Li's health and influence deteriorated, Xuanzong appointed Yang the new Chancellor owing to his skills in managing finances. Yang proved to be disastrously incompetent as chancellor, and his outright acerbic arrogance incurred the wrath of many generals and ministers, but remained one of Xuanzong's most trusted officials because the status of Consort Yang.

At Yang's core, he was as sycophantic and ambitious as An, but whenever he was outside the earshot of Xuanzong he didn't hide his disdain for all he regarded as his lessers- which consisted of likely 99% of the empire.

It surprised no one at court that the two frequently treated verbal jabs and did not respect the status of the other. Naturally, as Yang further consolidated his position and began to turn the Emperor against An, the general became paranoid and rebelled.

THEORY TWO: A SINNER WHO SAW IT ALL

The second theory naturally told a different story, though the outward appearance of the "plotpoints" are the same- the arrogance and roguery of Yang, the open hostility of the two men, the consolidation of Yang's power, and him turning the might of the Chancellery against An but the motivations are different. For despite the fact that fundamentally Yang possessed all of his unsavory traits, he was also the one to immediately see through An's facade, as clearly as Cassandra from Troy- for, as previously stated, both men were cut from the same cloth, and Yang not only realized the danger of having An in an arm's length and earshot of Xuanzong, but also the giant 164,000 strong veteran army that An possessed in his sleeves.

THEORY ONE: A DUEL OF VIPERS

After all, by the 750s, the inner court surrounding the aging Emperor was bloated with Consort Yang's relatives- her several sisters and uncles were all given titles, and her brothers, and uncles were all appointed to key positions around the Emperor, and by the time of his appointment- Yang GuoZong, who was in his early 40s was indeed a notorious gambler and a wastrel, but keen with the political scene to maintain Xuanzong's favor.

At Yang's core, he was as sycophantic and ambitious as An, but whenever he was outside the earshot of Xuanzong he didn't hide his disdain for all he regarded as his lessers- which consisted of likely 99% of the empire.

It surprised no one at court that the two frequently treated verbal jabs and did not respect the status of the other. Naturally, as Yang further consolidated his position and began to turn the Emperor against An, the general became paranoid and rebelled.

THEORY TWO: A SINNER WHO SAW IT ALL

The second theory naturally told a different story, though the outward appearance of the "plotpoints" are the same- the arrogance and roguery of Yang, the open hostility of the two men, the consolidation of Yang's power, and him turning the might of the Chancellery against An but the motivations are different. For despite the fact that fundamentally Yang possessed all of his unsavory traits, he was also the one to immediately see through An's facade, as clearly as Cassandra from Troy- for, as previously stated, both men were cut from the same cloth, and Yang not only realized the danger of having An in an arm's length and earshot of Xuanzong, but also the giant 164,000 strong veteran army that An possessed in his sleeves.

For as Yang observed, in late 751, An launched a major attack against the remaining Khitans who opposed him, advancing quickly to the heart of Khitan territory, but, hampered by rains, was defeated by the Khitan. An himself was almost killed, and, after retreating, blamed the defeat on two of the imperial generals Ge Jie (哥解) and Yu Chengxian (魚承仙), Yang had placed to monitor An- executing them. In 752, An quested thousands of soldiers to launch a counterattack against the Khitans.

Thereafter, Emperor Xuanzong refused to believe any suggestions that An was plotting rebellion,

FIRE (752-755)

In the spring of 755, matters were beginning to come to a head. When An Lushan submitted a petition to have 32 ethnically non-Han generals under him replace Han generals, this was accepted by Emperor Xuanzong, despite opposition from Yang Guozhong and his fellow chancellor Wei Jiansu who took An's use of non-Han generals as a sign of impending rebellion.

By now, exhausted of ways to prove of An's motives, Yang and Wei then suggested a soft approach and proposed that An be promoted to be Chancellor- though only in a ceremonial role and far- far away from An's base of power on the northeastern frontier, and in his absence that his three province garrisons be divided between his three deputies. An never gave an official response to this "promotion" in fact- it was silence, long gnawing silence that came from his frontier.

In the summer of 755 when An refused to- as per his duty to attend the funeral of an imperial Prince and did not- again as per custom offer to send a large number of horses to Chang' An for inspection and annual report that autumn, at last even the Xuanzong Emperor became suspicious. Allegations of An's bribes to the imperial eunuchs who were supposed to monitor him also reached the Emperor, who then had the bribed agent executed, and swiftly sent another eunuch, Feng Shenwei (馮神威) to the Fanyang garrison to finally summon An Lushan to answer for these allegations, the summons was again ignored.

When Feng arrived in the north around December 16, 755- instead of being greeted and finding a general waiting to bow and receive the imperial edicts. it was a massive army consisted of the best soldiers of the empire, fully equipped, provisioned, and assigned with an officer corp of mostly foriegners entirely loyal to An already on the march- an army that was so massive it was comparable to 40% of the entire empire's total forces.

→ Music: ← Sound of Heart Strings

When Feng arrived in the north around December 16, 755- instead of being greeted and finding a general waiting to bow and receive the imperial edicts. it was a massive army consisted of the best soldiers of the empire, fully equipped, provisioned, and assigned with an officer corp of mostly foriegners entirely loyal to An already on the march- an army that was so massive it was comparable to 40% of the entire empire's total forces.

ZERO HOUR (755)

An Lushan had used the pretext of claiming he had received "a secret edict" from Emperor Xuanzong to advance on Chang'an to remove Yang. It was at that moment- where 40% of the empire's best and most experienced troops barreled down toward the capital with nothing at all to stop them that Xuanzong and the entirety of the Tang court realized that for the last 12 years they had underestimated a consumate predator whose entire career consisted of deceiving his foes and leaving wakes- no whole fields of corpses.

[To be continued in Part 2.]

→ ☯ [Please support my work at Patreon] ☯ ←

Thank you to my Patrons who has contributed $10 and above:

You helped make this happen!

➢ ☯ Stephen D Rynerson

➢ ☯ SRS (Mr. U)

Comments

YOU sir, just guessed my next chapter, its going to be about Guo and Zhang Xun and Xuanzong' s flight from Chang' An

In general its very hard to find good Chinese armor from movies, that's why I try to pick out the few good ones out there (good being 75% accurate and above) and I try to make my concept art pieces are more authentic than those out there.

"... In 756, a contingent probably consisting of Persians and Iraqis was sent to Kansu to help the emperor Su-Tsung in his struggle against the An Lushan Rebellion..."

Concise History of Islam, p. 290 and Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam_during_the_Tang_dynasty

https://books.google.co.id/books?id=eACqCQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover

Though because I am not reading about this era at this time It will be some future day where I come back to this era again.

But feel free to stay tuned nonetheless. Cheers.

https://www.academia.edu/download/32693003/ArabSoldiersChina.pdf

They served under Prince Guangping and took part in the recapture of Luoyang and Chang'an. Do you have any plans to write about this topic?

It's been so long since I covered the Tang period but this is interesting.

I've thought about covering some Tang related topics but not this one for the near future, nope.

"Arab Soldiers in China at the Time of the An-Shi Rebellion" by Inaba Minoru

By the way, since you do not plan to write an article about this topic soon, is it alright for me to write it instead?

Cheers.